UC discovers new way of tracking jaguars

Brooke Crowley is using geochemistry to identify the secretive cats’ prime hunting grounds in Belize

How do you follow a predator so elusive that its nickname is “shadow cat”?

To track secretive jaguars in the forested mountains of Belize, the University of Cincinnati turned to geology and poop.

Brooke Crowley, a UC associate professor of geology and anthropology, can trace the wanderings of animals using isotopes of strontium found in their bones or the bones of animals they have eaten. This method works even with long-dead animals such as ancient mammoths.

Now she and her research partners are applying the technique to jaguar poop, or scat, found in the geologically diverse Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve in Belize. Claudia Wultsch, a wildlife biologist from the American Museum of Natural History and City University of New York, and Marcella Kelly, a professor of wildlife conservation at Virginia Tech, co-authored the study. Both have studied jaguars in Belize for more than a decade.

UC associate professor Brooke Crowley, left, works with her former student, UC graduate Maddie Greenwood, in a Crowley's lab. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The research found that jaguar scat provides isotopic signatures similar to those found in the undigested bones of prey to track the big cat’s movements across its varied landscape. Researchers examined strontium, carbon and nitrogen isotopes to identify the habitat and geology of prey upon which the jaguars were feeding.

The study demonstrates UC's commitment to research as outlined in its strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

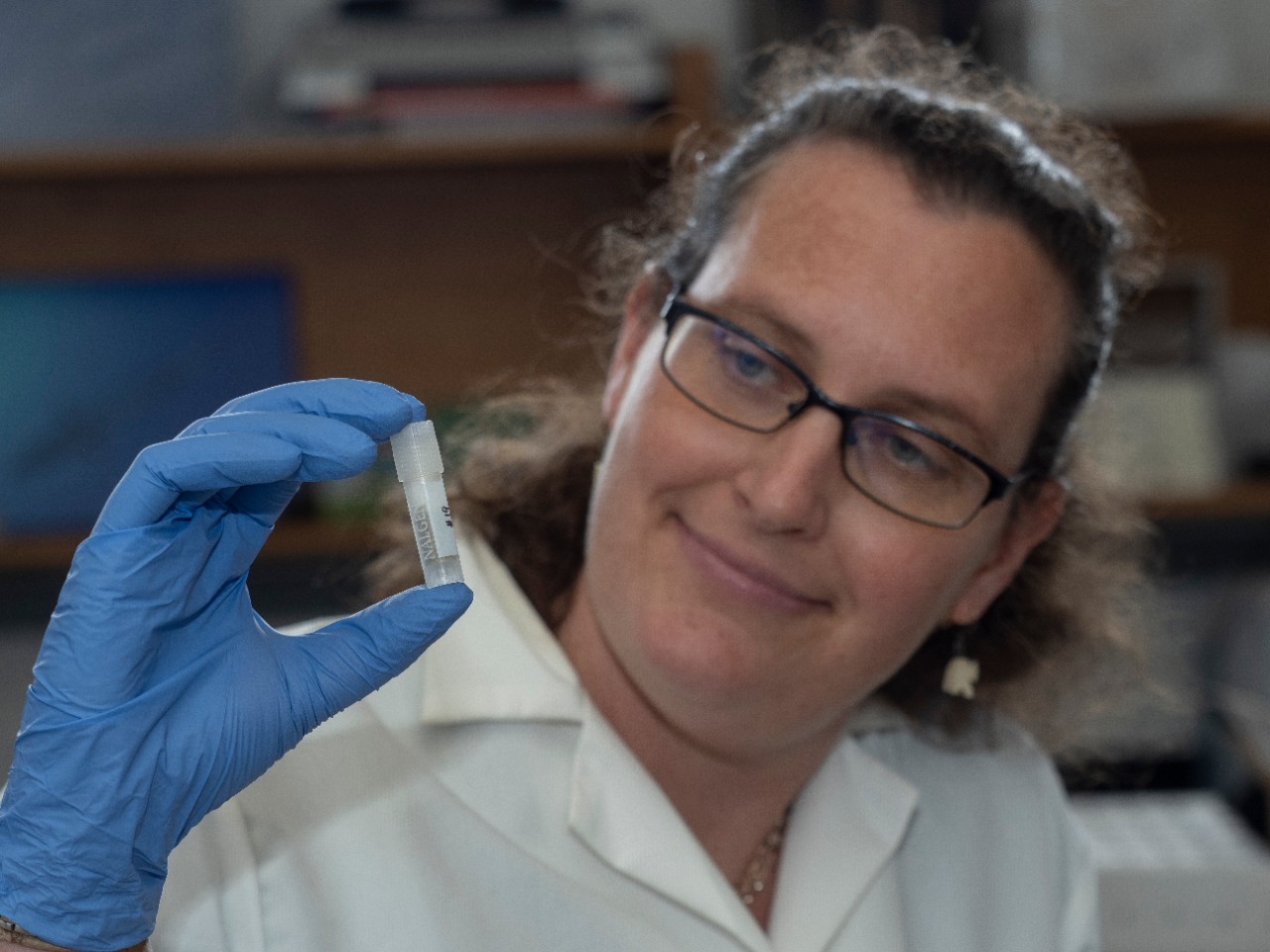

UC associate professor Brooke Crowley holds up a jaguar scat sample. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Strontium-87, which is radioactive, and strontium-86, which is not, provide a geological signature in the varied rock found across the reserve. The isotopes get absorbed in the food chain starting with plants that draw in minerals. Strontium then gets absorbed into the tissues and bones of herbivores that eat the plants and finally those of the predators that hunt them.

Strontium can be coupled with carbon isotopes, which reflect the type of vegetation in which an animal resides such as dense forest compared to open grasslands. This combination is particularly powerful for distinguishing where the cats hunt.

“The Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve is ideally suited for this kind of study because it has diverse geology and vegetation,” said Crowley, who works in UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

The findings suggest that an isotopic analysis of scat can be a powerful research tool for wildlife conservation and management. The study was published in August in the journal Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies.

UC associate professor Brooke Crowley examines samples in her quaternary paleoecology lab. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Jaguars are the largest big cat in the Western Hemisphere. Like leopards, they have a camouflaged coat with a unique pattern of spots and rosettes. They are opportunistic hunters, catching small birds and rodents or far bigger prey such as caimans, a type of crocodile.

The cats have disappeared from more than 40 percent of their historic range and are red-listed as near-threatened with extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. They are wide-ranging and wary, which makes them difficult to study in the wild.

“You have to be extremely lucky to see one in the wild,” Wultsch said.

Crowley has never seen a jaguar but did hear one calling one night in the rainforest on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Jaguars make a loud grunting call when they’re communicating with other jaguars.

“I thought it was kind of cool, but I wasn’t inclined to go check it out,” she said.

In this part of Central America, the jaguar’s stronghold is la Selva Maya, or the Mayan Forest, which covers parts of Belize, northern Guatemala and southeastern Mexico.

“It represents one of the largest blocks of contiguous forest left in Mesoamerica and is critical for jaguar conservation,” Wultsch said.

Researchers in Belize use specially trained dogs to find droppings from jaguars and other big cats. Here researchers study fresh jaguar tracks. Photo/Claudia Wultsch

Even this region has become increasingly fragmented by development over the last 50 years.

“One of the main objectives of our research is to assess how jaguars and other wild cats are doing,” Wultsch said.

Researchers have studied jaguars without capturing or handling the animals by setting up remote camera traps and collecting their scat. But researchers said isotopic profiling expands the tool box of noninvasive wildlife survey methods, offering a wealth of information from a single scat sample.

The UC study also suggested that jaguars in the reserve were not eating grazing animals such as livestock from area farms.

“Being able to document that isn’t happening is reassuring. They’re not competing for resources with people in the area,” UC’s Crowley said.

Vials of jaguar scat offer clues to the habitat needs and geographic ranges of the secretive big cats. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Finding animal droppings in thick rainforest is not easy, so researchers enlist the help of four-legged field assistants. Wultsch’s specially trained dogs have little trouble sniffing out the pungent droppings. The dogs also help researchers collect scat from other wild cats such as pumas, ocelots, margays and jaguarundis that inhabit the reserve.

“We were able to collect tons of poop — more than 1,000 feline samples,” she said.

Wultsch extracted DNA from the samples for a countrywide genetic study of jaguars and other wild cats. She found that despite some habitat fragmentation from human encroachment, jaguars in Belize were maintaining moderate to high genetic diversity. And while jaguars move across most landscapes of Belize, their movement in some protected but geographically isolated areas was limited, the study found.

Studying large carnivores in the wild is a challenge. Researchers sometimes capture big cats to attach a GPS collar to study their preferred habitat and movements. But sample sizes are often small.

“When I was putting together background research on radio-collared cats, so many times the study would be terminated because the cat would get hit by a car or get shot. There aren’t many jaguars out there,” Crowley said.

Brooke Crowley. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The isotope study gives exciting new insights into the ecology of elusive jaguars, Wultsch said.

“Jaguars face habitat loss and fragmentations across most of their range,” she said. “Noninvasive monitoring of jaguars using a multidisciplinary approach of isotopes, genetics and camera traps will help us understand how they are responding to environmental change and different human pressures.”

Previously, Crowley has used isotopic analysis to identify habitat needs of Henst’s goshawks in Madagascar and the migration of prehistoric horses in North America, among other projects.

While studying the digested bones in jaguar scat, Crowley discovered that little research has been done on whether digestion affects isotopic signatures. She is working with the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden to answer that question. She and her former student, UC graduate Maddie Greenwood, are studying the digested remains of scat from the zoo’s serval, Jambo, along with birds of prey to find out if there are any isotopic changes from digestion.

Strontium analysis holds tremendous potential for wildlife conservation, she said.

“Archaeologists have been using it longer. But it’s very powerful and underutilized in modern ecology and paleoecology studies,” Crowley said.

You don't have to be a conservationist working in South America to help jaguars and other rainforest animals. Crowley said consumer choices here in the United States and elsewhere can make a big difference in protecting natural resources.

"The decisions we make as consumers drive deforestation elsewhere," she said.

By buying locally-raised beef, responsibly grown coffee and other sustainably sourced foods, people can help prevent deforestation, she said. Likewise, many nonprofits such as the Sierra Club and the Nature Conservancy use donations to help preserve habitat and pay for conservation work.

"Conservation of our planet's remaining biodiversity is crucial. Biodiversity keeps everything in balance. We rely on the planet for our survival," she said.

Featured image at top: A jaguar stares back at a camera trap in Belize. Photo/Marcella Kelly/Virginia Tech Jaguar Project

UC associate professor Brooke Crowley, left, and her former student, UC graduate Maddie Greenwood, pose in Crowley's lab. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

Discover UC's commitment to Next Lives Here, the strategic direction with designs on leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.

Become a Bearcat

- Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100.

- Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

‘Undisciplined by Design’ podcast dives into the power of...

November 20, 2024

University of Cincinnati professor Aaron Bradley uses his “Undisciplined by Design” podcast to interview high-profile innovation leaders from across the United States.

Student filmmaker's animation movie 'The Wreckoning' debuts at...

Event: November 23, 2024 6:00 PM

Daniel Ruff's animation film "The Wreckoning" debuts at UC on Nov. 23. Ruff is among the first cohort of students to major in games and animation at UC.

CCM Director of Choral Studies Joe Miller named Music Director...

November 19, 2024

Vocal Arts Ensemble, the region’s premier professional vocal ensemble, has announced the appointment of Joe Miller as the fifth music director in the ensemble’s 45-year history, following a search that drew national and international interest.