UC professor and Emmy Award-winning journalist shares her father’s Holocaust survival story with lessons to inspire action against hatred and bigotry today

by Becky Butts

erched on the roof of the hospital

barracks at the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, Mendel

“Moniek” Lipszyc watched in awe as American

tanks and soldiers approached to liberate the

people held captive there. It was April 11, 1945

— a little less than a month before the Allied

powers declared victory in Europe and five

months before the official end of World War II.

He was 14 years old.

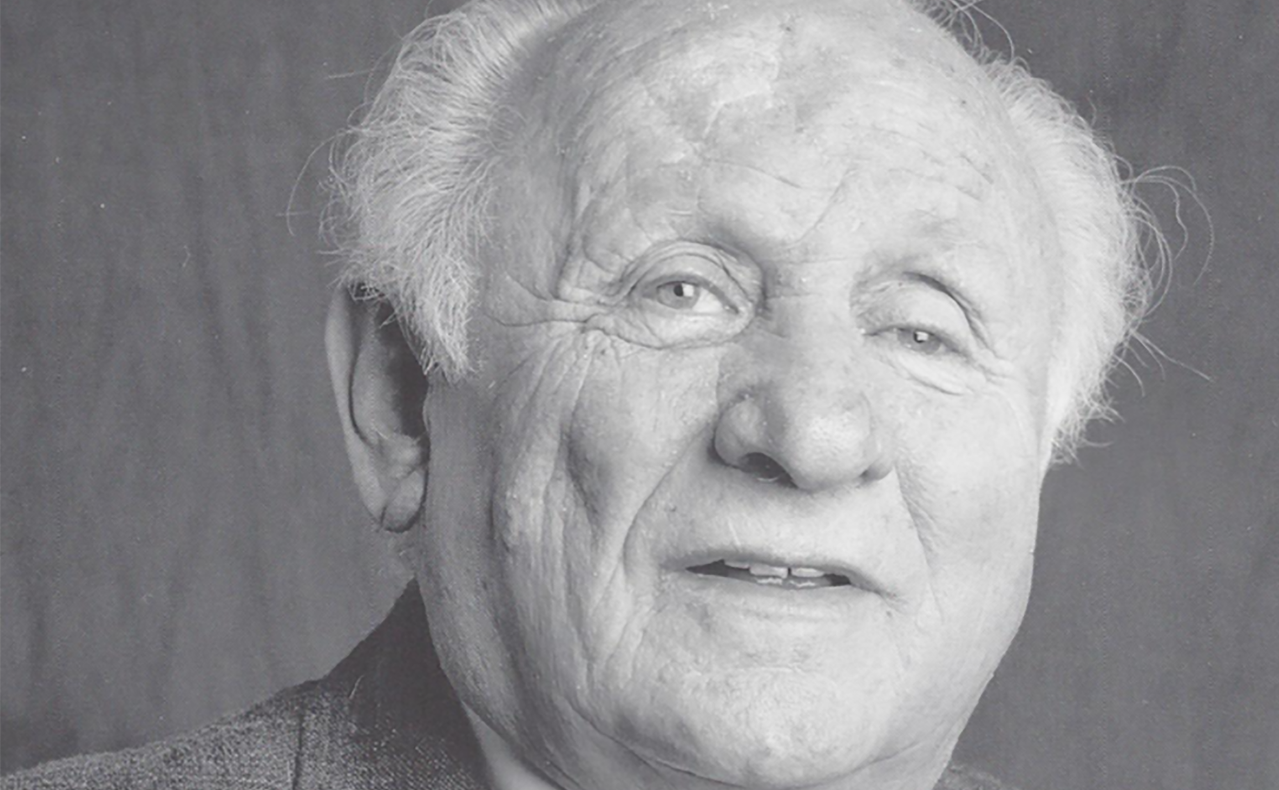

Moniek’s story of suffering and survival during the Holocaust begins with Germany’s invasion of his hometown in Czestochowa, Poland, on Sept. 3, 1939. Before the war, his family led an idyllic life. His father invented machinery that automated shoemaking, and the wealthy Jewish family lived comfortably in an apartment on the main avenue of town.

Only six of about 200 of his family members survived the war.

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that 6 million Jewish men, women and children were murdered by the Nazi regime during the Holocaust. The Nazi Party also targeted Roma people (then known as gypsies), people with disabilities, homosexuals and other groups who were persecuted for their political and ideological beliefs.

Moniek survived under the Nazi regime for five and a half years by hiding and living in sealed-off Jewish ghettos and enduring slave labor at two concentration camps, where he depended on his own quick thinking and the kindness of others to stay alive.

After he was liberated from Buchenwald, Moniek reconnected with his only surviving brother, Izio, and they began to rebuild their family. They relocated to a suburb in Hamburg, Germany, and then immigrated to Israel, where they changed their last name from Lipszyc to the Israeli name Limor. They later settled in Nashville, Tennessee, where Moniek worked at Izio’s architectural metal business until he retired. Moniek’s formal education ended at the third grade when the Nazis invaded Poland, but he went back to school and earned his GED after he moved to the U.S.

In the past, Moniek shared his Holocaust experience with students and community members, but Alzheimer’s disease has severely impacted the 89-year-old’s memory and health. Now, his daughter Hagit Limor, UC professor of electronic media and an Emmy Award-winning journalist, is retelling her father’s Holocaust story with a message of hope.

“For years, I’ve watched as my father lost the words to a story that only grew in relevance,” says Limor, a professor at UC’s College-Conservatory of Music (CCM). “Eventually he could no longer share his wisdom with students as he had for decades before. I want to create a mechanism for relating these lessons to outlive not only my father, but his daughter as well.”

Limor is working with students, faculty and staff to create a groundbreaking audience immersion play and virtual reality experience to share the history of the Holocaust from her father’s perspective. “Hope After Hate: Moniek’s Legacy” connects people to history in new ways, builds a platform for civil discussion and challenges viewers to consider their actions when confronted with hatred and bigotry today.

Telling a historical story in an innovative way

In October 2019, Limor’s Media Topics class of 15 students traveled to Poland and Germany on a 10-day trip to retrace her father’s journey. They used 360-degree cameras and drones to capture photos and videos to use in the “Hope After Hate” project.

The multidisciplinary class was composed of undergraduate and graduate students majoring in e-media, acting, international affairs, political science, geography and history. They were joined by Limor’s brother, Yoram, as well as Jodi Elowitz, director of education and engagement at Cincinnati’s Nancy & David Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center, and Susan Felder, a CCM assistant professor of acting who is adapting Limor’s memoir of her father’s Holocaust experience into a script for the immersive play.

“I purposely chose students from across the university and from various backgrounds,” Limor says. “People who could think from different parts of their brains. Together, we’ve been able to create something that is so much richer, more varied and nuanced than it would’ve been if it would’ve only come from my own students.”

“Hope After Hate” will be an innovative, new kind of theater — part play, part video and part virtual reality. Projections of historical settings will surround the audience during the performance, creating a virtual set in which they sit and interact with the actor portraying Moniek. They will be transported into the attic where he hid with his family as a child, into the Hasag-Pelcery labor camp where he was enslaved for more than a year as an adolescent, into the cattle-car train that transported him to Buchenwald when he was 14 and into the camp itself, where he was an inmate for four months. The project explores how people struggle to hold on to their humanity when surrounded by hate and fear.

“I feel a responsibility as a human being to find out what’s the best about us and the worst about us and to shine a light there,” says Felder on her experience adapting the script for the play. “I have faith in humanity, and when that faith is rocked, I want to know what makes us capable of that.”

The student-shot photos and videos will be used to create the virtual set, along with historical images and artwork. Limor and Felder are collaborating with Sharon Huizinga, UC assistant professor of lighting design and technology at CCM, on how to create the projections. They are working on finalizing the script and production elements needed for the play, with the goal to workshop it in fall 2020 and present it at CCM in 2021.

The “Hope After Hate” team is also creating a separate 15-minute virtual reality module

that will immerse users in Moniek’s story with goggles and hand sensors. UC’s Center for Simulations and Virtual Environments Research (UCSIM) is building the VR experience with the 360-degree photos and videos that digital media collaborative and e-media student Caleb Smiley captured while on the trip.

The VR experience is being developed for a recently released all-in-one wireless headset, which will make it easier to deploy the “Hope After Hate” module in classrooms. Virtual reality is not new, says Chris Collins, founder and technical lead at UCSIM, but the cheaper and more accessible headsets are. UCSIM is seeing an explosion of uses for VR and is exploring different ways to use the technology in teaching and research.

“Virtual reality is not a passive experience,” Collins says. “It leverages a lot of the same psychology as video games. We know that video games can be very active and engaging. What makes people want to play them is that you feel empowered and that you have agency in that game. We want learning to be like that.”

Limor says that the VR module will be complete by June 2020. The plan is to then create kits that the “Hope After Hate” team can provide to middle school and high school classes who are studying the Holocaust.

“My whole goal here is that this is a project that is carried forward by today’s young people because they are the ones who are going to make any change in the future,” Limor says. “This is a way of empowering them and making them more connected with the entirety of their political and social landscape so they feel like they have a voice.”

Moniek’s legacy: Humanity in the face of hate

Everyday people stood by and ignored the atrocities of the Holocaust. “Hope After Hate” aims to immerse people in Moniek’s real-life events in an effort to turn bystanders into “upstanders” who will take action to prevent acts of hatred and bigotry today.

“I think that we need to humanize and remember the history of the people who survived and experienced the Holocaust on an individual scale,” student Smiley says. “You can talk about the Holocaust in general details, but it doesn’t draw as strong of a connection as it would if you talk about a specific person’s story.”

Moniek’s survival has a lot to do with his own resourcefulness. He stood on mounds of snow, gravel and rocks to make himself appear taller during selections, where the Nazis separated their captives into groups. He stayed hydrated by drinking melted snow when he was crammed into a cattle-car train en route to Buchenwald, and he helped those around him by sharing the water.

Moniek also had to depend on others to help keep him safe. When he was 12 years old, his uncle Jakob smuggled him out of the attic where his family hid before they were discovered by the Gestapo. This spared him from being sent to the Treblinka extermination camp with his mother, Mirla, and brother, Wowek. His uncle’s act of bravery will be explored in

a scene during the “Hope After Hate” virtual reality experience. The user will interact with the scene as if they are another child in the family who is also in hiding in the attic.

In another VR scene, the user will stand next to Moniek when his cousin Rhuzha sneaks bread to him without being caught by the Nazi officers at Hasag-Pelcery. This small act of kindness helped him survive in the dirty and overcrowded cattle-car during the three-day trip to Buchenwald. The prisoners, who were already malnourished and sick, were not given food, water or blankets during this freezing commute.

Another scene will turn the user into an assistant in the hospital at Buchenwald, where 14-year-old Moniek befriended an older political prisoner named Leon who helped him survive. Leon gave him a job so he could stay at the hospital, which had better living quarters than the typical barracks at the concentration camp. At the hospital, Moniek had a clean bed, heat from a nearby stove and access to more food than the typical one slice of bread and watery soup provided to most of the prisoners each day.

The user will join Moniek in present-day Buchenwald for the final VR scene. The narrator portraying him will talk about the liberation of the camp while reflecting on the people who helped him survive. He will then ask the user to think of how they can stand up to bigotry today.

“I think we owe it to everyone who was lost in the Holocaust to educate ourselves,” says international affairs student Gianna Vitali, who wants to petition legislators to require Holocaust education in school curriculums. Only 12 U.S. states require Holocaust education as part of their secondary school curricula; Ohio is not one of them. “It was eye-opening to see what humans are capable of doing to other humans. I feel like I have an obligation to make sure that this never happens again.”

Students in Limor’s class went to the present-day remnants of the locations from her father’s Holocaust journey. They stood in the attic of Moniek’s home in Czestochowa and visited the memorial train depot where 40,000 Jews were put on trains to Treblinka.

Then they visited the town’s decrepit Jewish cemetery, which is overgrown with weeds and shrubbery because it was abandoned during WWII. The gravestones are broken and worn; some have bullet holes in them from when the Nazis executed Jewish people in the cemetery. Moniek’s father was one of the last people to be buried in this cemetery, but his family can’t find his grave. Limor did find the grave of her great-grandmother, who was buried there before the war.

“There were 200 people in my extended family, and we only know of six who survived,” she says. “We don’t know what happened to any of these family members, and we have no graves to go to. This one grave stands for my entire family.”

They also visited the Hasag-Pelcery labor camp in Czestochowa and the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany. The class explored other historical sites as well, including what’s left of Poland’s Warsaw ghetto and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

“No one is really ready to see those places, but I also think it’s really important for

people — especially young people — to go and witness it,” says acting student Carlee Coulehan.

Troubling contemporary connections

When Professor Limor’s 14-year-old son began asking her questions about discrimination and bullying he witnessed at school and in current events, she saw parallels between his experience now and her father’s experience leading up to the Holocaust.

“I realized that some of what I was hearing was similar to what my dad had told me about when I was a little girl and he recounted his childhood,” she says. “There is so much disappointment with some of the hatred and bigotry in media, politics and the world stage right now. This project seeks to fight hatred wherever it exists. It is not political at all. It is about humans caring for other humans.”

Throughout the trip, the students made connections between the historical settings and present day. While standing in line waiting to enter Auschwitz, Vitali read a current news story about young students who forced a Jewish boy to lick their shoes clean. Graduate history student Shawn Liming was disappointed to see “Ku Klux Klan” graffitied on a wall near Moniek’s childhood home.

“The whole reason why we’re here is to stand up against things like this,” Liming says.

The students are creating their own projects related to “Hope After Hate” to reach multiple audiences in different ways. A team of e-media majors is working on a documentary that features nightly commentary students shared after each day of the trip. Student teams are

also creating a podcast, video blog, social media campaigns and are actively updating the “Hope After Hate” website with news on the project.

Jodi Elowitz of Cincinnati’s Holocaust & Humanity Center was impressed by the students during the trip and by how committed they are to “Hope After Hate.”

“Any time I spent with the students was most special to me, as they will be the ones to continue to tell these stories,” she says.

“Hope After Hate” fits perfectly into the center’s mission to ensure that the lessons

of the Holocaust inspire action today. When the project is complete, the Holocaust & Humanity Center plans to use it in its educational outreach.

Limor sees her son and students searching for ways to confront discrimination today, looking for ways to act. She set out to create “Hope After Hate” with the mission to preserve her father’s memory and share it in an immersive way so that people can connect with it, inspiring discussion and action.

“The whole reason for “Hope After Hate” is to try to come up with a tool to open communication about bigotry of all kinds so that people have at least an ability to start the conversation,” Limor says. “I feel that’s the beginning of action — to talk to each other.”

“Hope After Hate” is sponsored by Cincinnati’s Holocaust and Humanity Center, and has already received support from private donors as well as Cincinnati’s Jewish Innovation Funds and the CCM Harmony Fund. This support offset travel expenses during the study abroad trip and funded some production expenses. However, the class is still actively collecting donations for projectors needed for the play and virtual reality equipment. Visit hopeafterhate.com for updates on the project and to learn how to get involved.

FEATURE STORIES

Hope after hate

UC professor and Emmy-award winning journalist shares her father’s Holocaust survival story with lessons to inspire action against hatred and bigotry today.

Good neighbors - better partners

UC, Cincinnati Public Schools work together to create something special at a new school.

Role reversal

UC breast cancer surgeon Beth Shaughnessy learns firsthand what it’s like to overcome cancer and keeps kindness and positivity at the center of her healing

Traffic of tomorrow

More driverless cars. More networked roads. More naps. UC is helping change how we drive.