UC researcher helps lead the fight to end the scourge of suicide

ennifer Wright-Berryman wants the pain to stop and the silence to end.

The pain that young people feel from the growing number of pressure-inducing factors in their lives, and the societal silence about suicide.

By Bill Bangert

Photos by Colleen Kelley

Wright-Berryman, an assistant professor in the School of Social Work in UC’s College of Allied Health Sciences, started studying suicide about five years ago. Her interest in the subject was spurred by the suicides of several young people her daughter’s age in their community of Columbus, Indiana.

“It was a personal mission to try to do something to bring suicide prevention into my community,” says Wright-Berryman. “My daughter said, ‘Mom, you’re a social worker, go fix this problem.’ So I started working with a team of people looking at different models for school-based suicide prevention, and we stumbled onto Hope Squad.”

The Hope Squad program, founded nearly 20 years ago in Utah, is a school-based peer support team that partners with local mental health agencies. Students nominate peers who are trustworthy and caring to join the Hope Squad. Squad members are trained to watch for at-risk students, provide friendship, identify suicide-warning signs and seek help from adults when needed.

Wright-Berryman contacted Hope Squad to learn more about what, if any, data the organization had.

“They said they were sitting on piles of data but didn’t have a research collaboration that was needed to be able to study the program,” she said. “I told them I was a researcher, and my background is in implementation science.

“It was quite a gold mine of data that they were collecting from counselors at schools.”

Jennifer Wright-Berryman, an assistant professor in the School of Social Work in UC’s College of Allied Health Sciences, uses her expertise to help curb suicide attempts by working with organizations such as Hope Squad to lend a better understanding of the issue.

Now, as the national lead researcher for Hope Squad, her analysis of the data revealed that schools with Hope Squad programs show an increase in referrals of students with suicidal thoughts.

“We started seeing that as a Hope Squad got established in a school, there was what’s called in research ‘a dosing effect’ — the more you get of something, the more you can change the outcome,” Wright-Berryman says. “We saw that school culture was changing and students started to refer themselves. As a result, after the first year of the program, the Hope Squad refer- rals go down, and students’ self-referrals go up. By looking at the data, we now understand that the stigma of suicide decreases which improves help-seeking.”

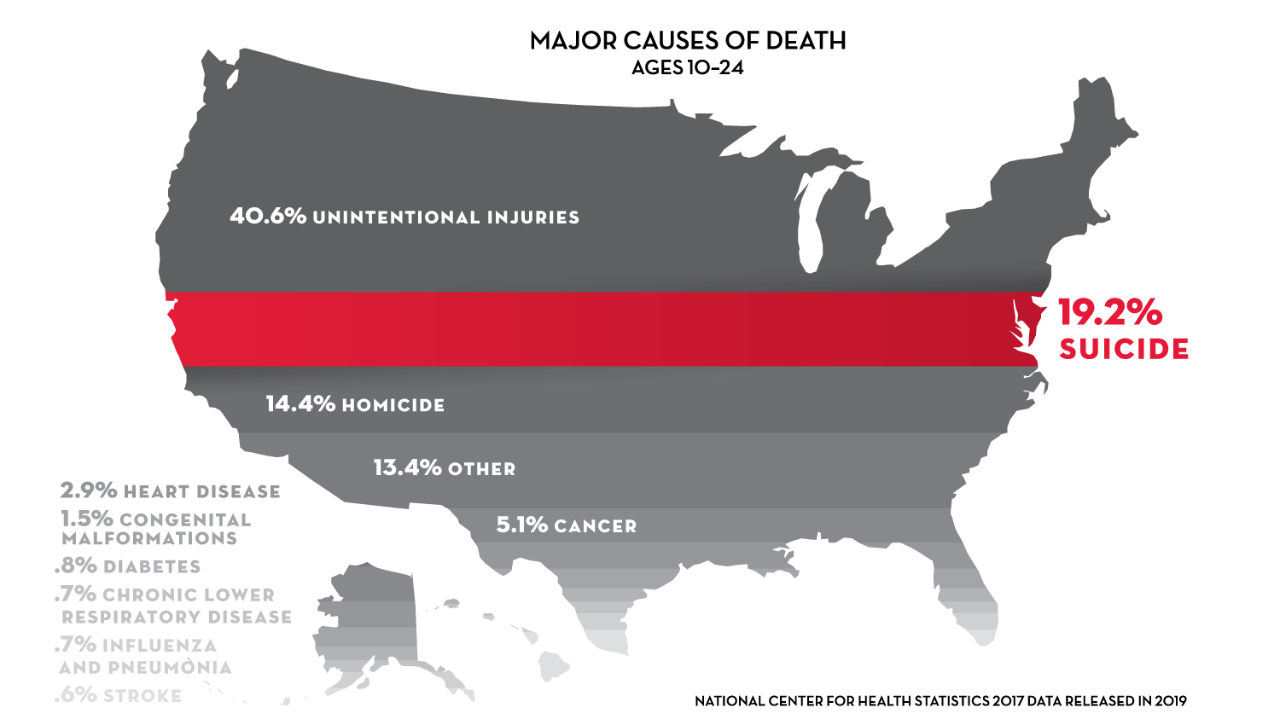

Suicide rates among teens and young adults have reached their highest point in nearly

two decades, according to a report published in June 2019 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Suicides among 15–19 year olds increased by an annual rate of 10 percent between 2014 and 2017, and was the second leading cause of death for that age group as of 2016.

The work of the Hope Squad at Summit Country Day School in Cincinnati — now one of several schools in the area to have one — is visible from the notes left on lockers lining the hallways. The handwritten words of encouragement include these: “You’re amazing,” “You are loved,” “Stay positive” and “You got this.”

Amotij Kaur says she was surprised to learn that she was chosen by her peers to be a member of the Hope Squad at Lakota West High School, Cincinnati, before the start of her senior year last summer. She battled depression in middle school, and one day when she was at a particularly low point, a friend, having no idea of her level of sadness, shared a YouTube video called “To This Day” by Shane Koyczan.

“It’s an amazing video,” she says. “He’s a slam poet, and it talks about how we go through our lives feeling down about ourselves, but as we live each day there’s a voice inside of us that tells us to keep moving and how important it is to listen to that voice.”

Kaur says after watching that video a few times, she started to focus her thinking more on how she could make the world around her better. She describes it as a servant-leadership mindset, one focused on helping people with troubled feelings.

“That fulfillment of helping the world around me just made me feel better about my own life and how I felt about myself,” Kaur says.

The Hope Squad at Lakota West consists of 60 to 70 members, all trained in suicide prevention through evidence-based modules.

The following are the major causes of death amongst children ages 10-24: 40.6% unintentional injuries | 19.2% suicide | 14.4% homicide | 13.4% other | 5.1% cancer | 2.9% heart disease | 1.5% congenital malformations | 0.8% diabetes | 0.7% chronic lower respiratory disease | 0.7% influenza and pneumonia | 0.6% stroke. (National Center for Health Statistics 2017 Data - released in 2019)

Does she think Hope Squad saved any lives at Lakota West during its first year at the school?

“One-hundred-and-ten percent,” Kaur says. “For the 2018–19 school year, 40 percent of all referrals made at Lakota West were by Hope Squad members about a student who needed help. In my first year at HS, I referred about 15 kids, and a few of those were emergency situations where someone was considering hurting themselves immediately. I know for a fact that we saved lives that year.”

Wright-Berryman says having Hope Squads in school helps spread a contagion of, well, hope.

“The kids are saying if the school cares enough to start this program, that’s meaningful to recognize that they’re truly valued,” she says.

“Once those messages sink in and take hold of a school, culture starts to change, stigma goes down, help-seeking goes up and those are impacts of a Hope Squad, and that’s what we want to see.”

Wright-Berryman says her research of schools with Hope Squads will continue to expand by comparing data of schools with Hope Squads to schools who have yet to implement the program. Her research team surveyed around 3,500 students and that data is in the process of being analyzed.

She also recently completed a study of parents of Hope Squad members to find out what qualities their children possess to cause them to be chosen by their peers. The top trait was inclusivity.

Looking ahead, she wants to take this to communities and get neighbors talking and reconnected.

“If people are just depressed or feeling gloomy, we may need to talk about it, no matter how seemingly insignificant the issue is,” she says. “If we start doing that more as a society, we will prevent suicides.”

FEATURE STORIES

The nonprofit Village Life Outreach Project has sent hundreds of volunteers from UC to three remote villages in East Africa since it started 15 years ago, an effort that has deeply impacted countless lives on both sides of the world.

UC has invested $100,000 in Cincinnati nonprofits to commemorate the Bicentennial's impact in the community.

The new home of the University of Cincinnati’s business college is built to foster collaboration, adapt to future needs. Also featured is the brand new Allied Health Sciences building.