UC prof talks walls, wars and migrants’ will

University of Cincinnati professor Leila Rodriguez discusses the global refugee crisis at the American Anthropological Association’s annual conference

The politics of fear is making the study of immigrants more difficult for social science researchers, a University of Cincinnati professor said.

“We’re seeing a wave of increasing nationalism in countries today. That goes hand in hand with the rejection of immigrants,” said Leila Rodriguez, UC anthropology professor.

Rodriguez has spent her career examining the causes and consequences of mass migration. She took part in a panel discussion this month on the global refugee crisis at the annual American Anthropological Association conference in San Jose, California.

Rodriguez's work demonstrates the value that UC places on research as part of its strategic direction, Next Lives Here.

More people today are fleeing their homes than in the history of the world. An estimated 68 million refugees were displaced in the past year by forces such as war, famine and violent crime.

“We’re seeing more extremism, most recently in the presidential election results in Brazil,” Rodriguez said. “They give nationalist speeches that play into people’s fears because immigrants make an easy scapegoat.”

Central American migrants carry strollers, bags and other possessions over their heads while crossing the Suchiate River between Guatemala and Mexico. Photo/Santiago Billy/AP

Newly elected Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro in interviews called immigrants from Haiti, Africa and the Middle East “the scum of the earth,” according to news reports. Curtailing Central American immigration was a keystone of President Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign and remains one of his top Twitter and campaign subjects.

As a result, Rodriguez said, social scientists have a harder time persuading immigrants to share their stories because they fear reprisals from a society that vilifies them.

“Our first concern is it’s harder to get access to immigrants as a research subject under these conditions,” she said. “People are afraid to talk. They think we’ll tell the government who or where they are. It takes longer to build relationships with these communities so they’ll open up.”

Mountains have never stopped humans from migrating. Oceans, rivers and deserts have not stopped humans. A wall is not going to stop humans when they want to move.

Leila Rodriguez, UC anthropology professor

UC anthropology professor Leila Rodriguez has studied a variety of immigration issues in her nine years at UC. Photo/Ravenna Rutledge/UC Creative Services

Rodriguez experienced firsthand what it was like to live in a new place when her family moved from its native Costa Rica to Pennsylvania for five years so her mother could finish her doctoral degree.

“The process of changing schools, of becoming an immigrant and returning to my home country sparked my interest in cultural differences,” Rodriguez said. “They say you study what you are. Being a child migrant definitely set the tone for the rest of my life. It was the first time I became an ‘other,’ an outsider.”

Rodriguez is teaching a UC honors class this year on the global refugee crisis. She and her UC students will travel to Munich, Germany, to see firsthand how some of the more than 1 million refugees there are adjusting to life in Europe since they started arriving in 2015.

Students will talk with government officials and nonprofit groups, visit refugee shelters and spend time with refugee students at local universities, Rodriguez said.

Germany has set up dorm-style refugee centers for asylum seekers, some of whom have expressed frustration with living conditions while they await news on their immigration status. Germany also is seeing a growing anti-immigration public backlash that has featured public protests.

Related Research

UC geography professor Tomasz Stepinski created a new global map showing how landscapes have changed in the past quarter-century. The interactive map helps explain current events such as the migrant caravan heading to the United States.

Rodriguez’s academic research at UC has examined Nigerian immigrants’ entrepreneurship and transnationalism, Costa Rican emigration and the integration of unaccompanied Central American child migrants. But lately Rodriguez has been inundated with requests from immigration lawyers to draft affidavits explaining the pressures that make people flee their homes.

She published a paper last year on the use of cultural-anthropological appraisals in judicial hearings.

“It’s really hard to say no, so I do a lot of pro bono work. Every month I get a new request, and I have to spread out the work or turn them down,” she said.

In one affidavit she explained why a young, homeless asylum seeker from Guatemala fit the criteria for refugee status.

“Guatemala is a beautiful country. Any of us could visit and wouldn’t experience this kind of violence,” she said. “But if you’re a young man living on the streets, you’re at high, high risk of being recruited into a gang. You either say yes or you’re killed or you leave.”

She has seen a growing demand for social scientists to help courts determine eligibility for asylum, she said.

“I can’t speak for everyone, but it’s forced us to become more activists than pure researchers,” she said.

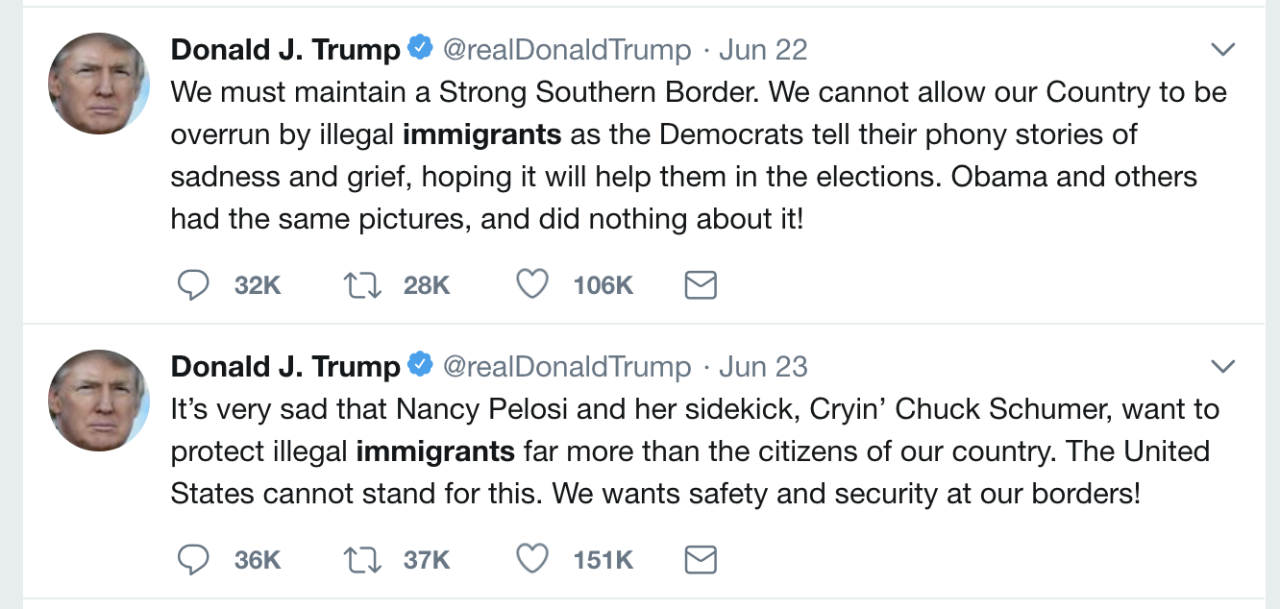

President Trump tweets in June about Central American immigration.

The immigrant experience is changing, too, she said. In the 1900s, the United States saw waves of European immigration during what Rodriguez calls “the assimilationist years.” Immigrants were expected to shed their native cultures and languages in exchange for their new American ones.

“But we don’t live in a time when you have to drop every indicator of your original culture and assimilate,” she said. “We understand that you can hold onto your culture and still be American.”

Still, Rodriguez said, there is always pressure to assimilate from some quarters of politics and society. Regardless of how easily immigrants adjust to their new lives, one thing hasn’t changed, Rodriguez said.

“No matter how much or little an immigrant adapts to their host society, their kids will become Americanized,” she said. “And by the time they have grandkids, you can’t tell them apart from the mainstream American culture.”

Rodriguez said the United States’ recent focus on border walls and visa restrictions is having the opposite intended effect. Ironically, making the border less porous prompted more seasonal workers to remain in the United States permanently and even send for their families.

Immigration scholars largely agree that you need to increase the number of temporary work visas, not decrease them, she said.

“Mountains have never stopped humans from migrating. Oceans, rivers and deserts have not stopped humans,” Rodriguez said. “A wall is not going to stop humans when they want to move. Walls don’t keep people out. They keep people in who otherwise would have left.”

Featured image at top: UC anthropology professor Leila Rodriguez. Photo/Ravenna Rutledge/UC Creative Services

UC professor Leila Rodriguez will be leading a UC honors class to Germany to learn more about the global refugee crisis. Photo/Ravenna Rutledge/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

What parvovirus is and why it's on the rise

July 10, 2025

An infectious virus common in children is on the rise in the Tristate. The Cincinnati Health Department is warning of a rise in parvovirus in Hamilton County. The illness can present itself as a rash on the cheeks and is often called “slapped cheek” disease but can present more serious concerns in pregnant women. Kara Markham, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine recently appeared on Cincinnati Edition on WVXU to discuss how parvovirus is transmitted, the risk of serious cases and how to prevent it.

UC joins international Phase 1 trial testing CAR-T therapy for MS

July 10, 2025

The University of Cincinnati Gardner Neuroscience Institute is a trial site for a multicenter, international Phase 1 trial testing CAR-T cell therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis.

Hoxworth issues urgent call for blood donors

July 9, 2025

Hoxworth Blood Center, University of Cincinnati, is calling on the Greater Cincinnati community to make a lifesaving blood or platelet donation to help local patients in need during the critical summer months.