UC students take on malaria prevention

Bed nets protect sleeping children from malarial infection. So why aren’t more parents using them? University of Cincinnati geography students are exploring the question.

University of Cincinnati researchers are trying to understand why some parents who live in malarial zones are not embracing one of the simpler safeguards against the disease.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne illness that kills more than 435,000 people each year, according to the World Health Organization.

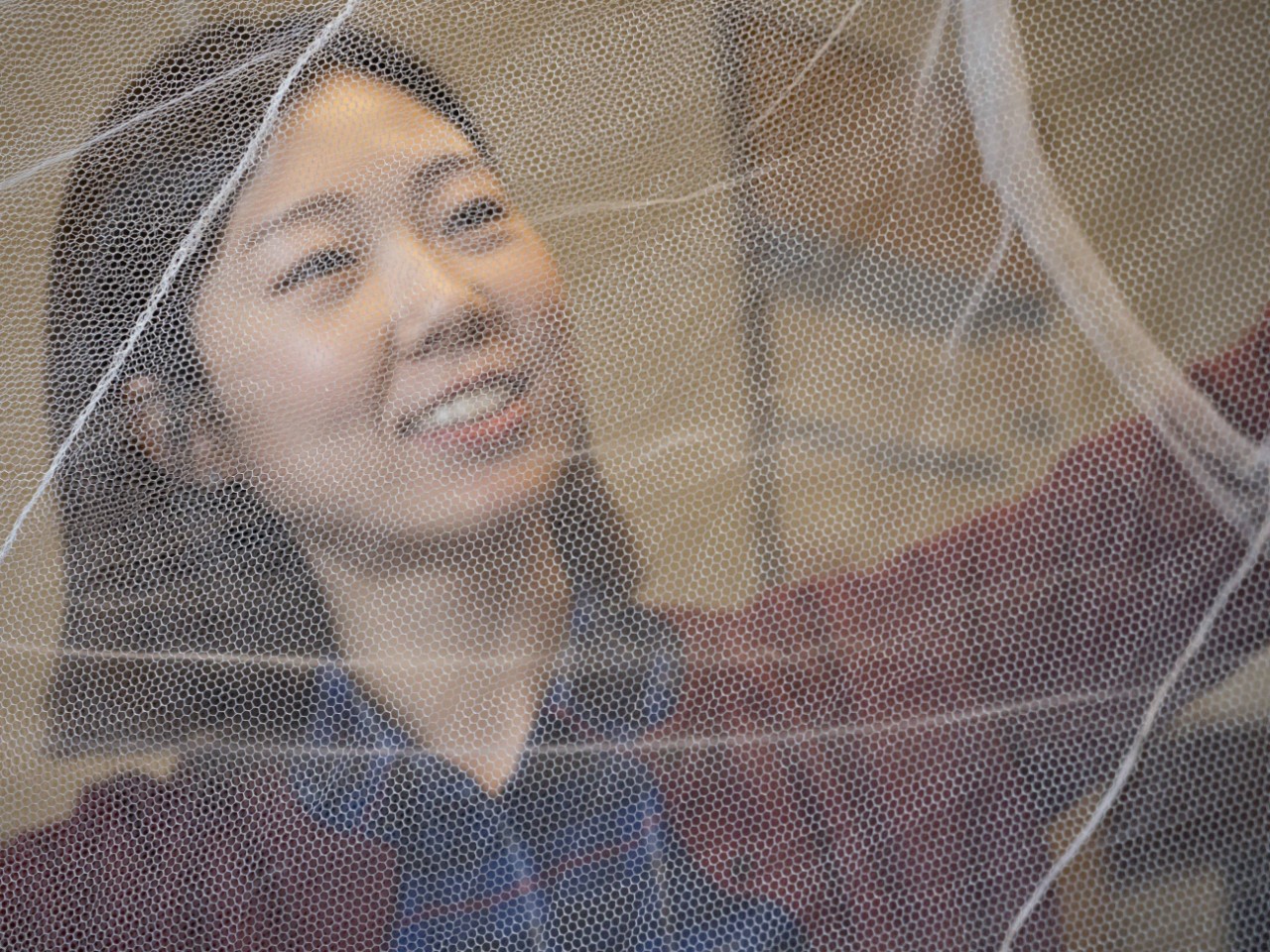

Health officials say draping your bed with a protective mesh net is an effective way to avoid mosquitoes at night when the pests are most active and when people, especially children, are most vulnerable — when they’re sleeping.

Despite the benefits, researchers in UC’s Health Geography and Disease Modeling Laboratory found that bed nets are not being used everywhere they’re available. They wanted to know why. They will present their findings this week at the American Association of Geographers conference in Washington, D.C.

The study could help health organizations identify where malaria-prevention education is needed most, said Diego Cuadros, a UC assistant professor of geography in UC's McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

“Ultimately, each government has a different way of approaching this issue. It depends on the public health mission of each country,” he said.

The research demonstrates UC’s commitment to research as outlined in its strategic plan called Next Lives Here.

The problem is that in some areas, this contra-intervention isn’t working. People aren’t using the bed nets for their intended purposes.

Diego Cuadros, UC assistant professor of geography

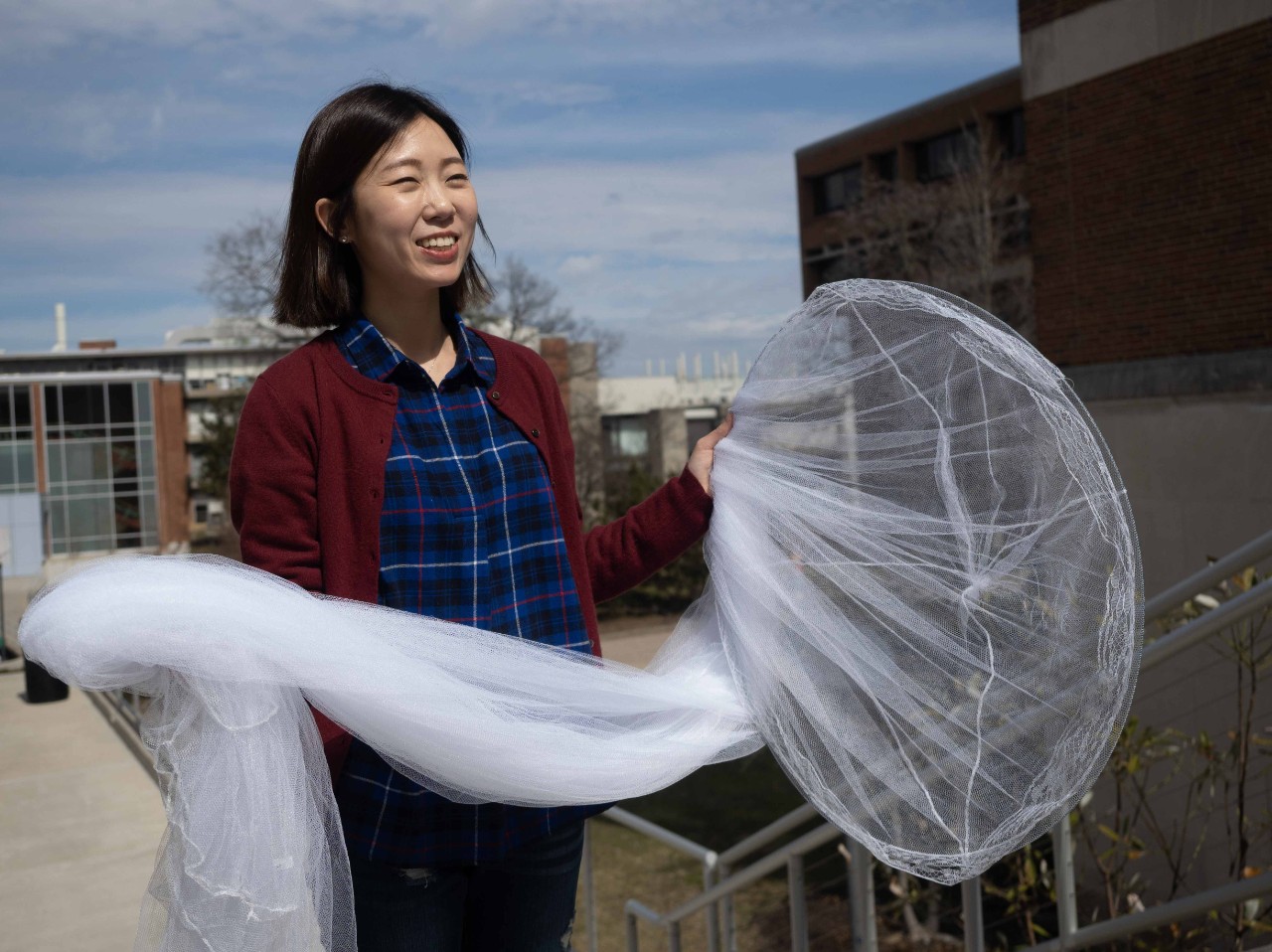

UC geography student Hana Kim holds a mesh bed net. The hoop hangs from the ceiling and its mesh can be draped over a bed or crib to protect people from mosquitoes. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

More than 624 million insecticide-treated bed nets were distributed in malaria zones around the world between 2015 and 2017, according to the World Health Organization. Most were donated free of charge by health charities. Countries around the world spent $3.1 billion on malaria prevention in 2017.

“The problem is that in some areas, this contra-intervention isn’t working,” Cuadros said. “People aren’t using the bed nets for their intended purposes. They’re using it for fishing or they sell them. Nobody has explored the situation in detail.”

Hana Kim, a graduate student and lead author of UC’s project, grew up sleeping under a bed net in her home in South Korea, where malaria remains an uncommon but persistent threat.

“Malaria cases have been declining since 2010. But malaria remains the second-leading cause of death from infectious diseases in Africa next to HIV,” Kim said.

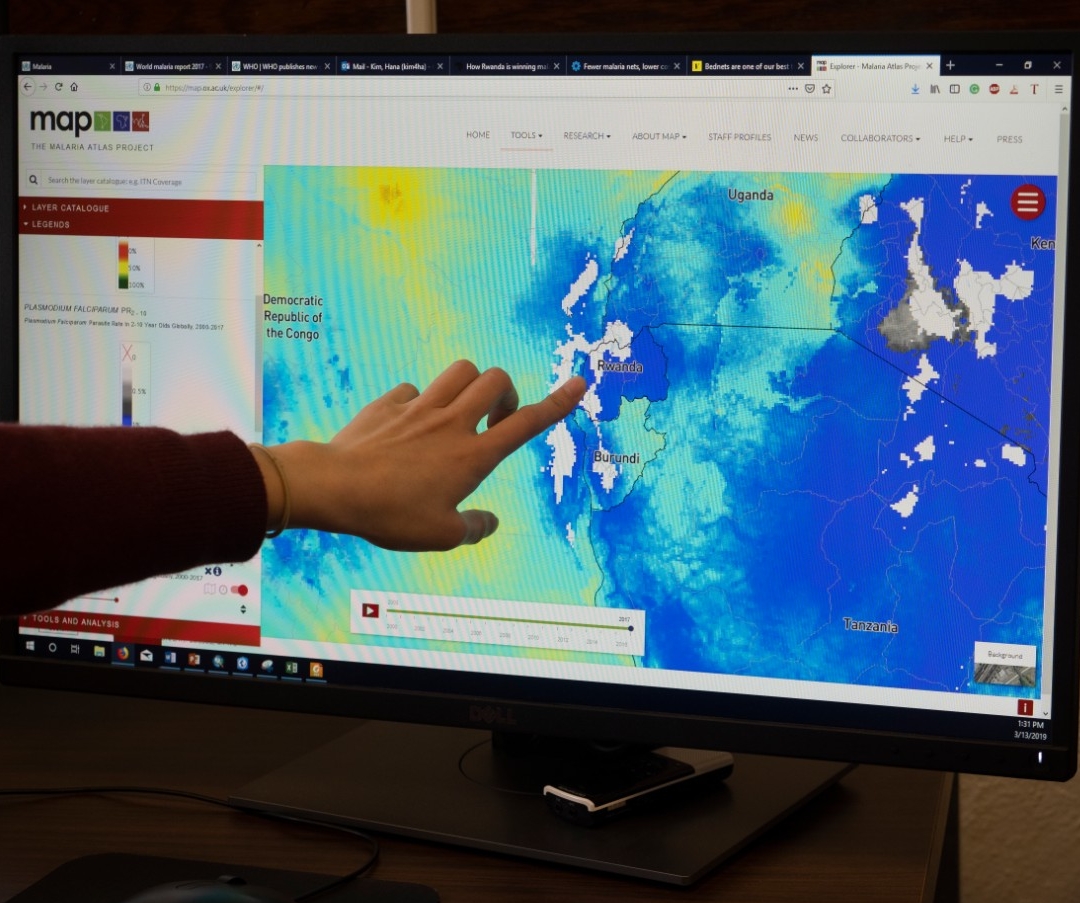

UC student Hana Kim sits at a computer talking about the results of her study into the prevalence and use of bed nets in 10 African countries. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The World Health Organization said about 219 million cases of malaria were reported globally in 2017. This was a slight increase over the previous year. Children under 5 are especially vulnerable to the disease, health officials say. They represent nearly two-thirds of fatal cases.

But Kim said some countries have been more effective than others at minimizing malaria exposure. Rwanda, in particular, saw 430,000 fewer cases in 2017 than the year prior. Kim said the increasing use of bed nets could be a major reason for this decline.

Malaria was a scourge in the United States for most of the country’s history. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers undertook massive water-diversion programs to remove standing water where mosquitoes breed. And the widespread use of the insecticide DDT was effective at eliminating populations of mosquitoes that carried a parasite responsible for the disease. DDT was banned in 1972 in the United States because of its devastating effects on wildlife and the food chain. The EPA now considers it a “probable human carcinogen.”

Today, malaria is found in largely equatorial or tropical countries around the world.

Bed nets are a very good strategy to prevent mosquito bites. They’re durable and last a long time compared to mosquito sprays that are not as effective or long-lasting.

Hana Kim, UC geography student

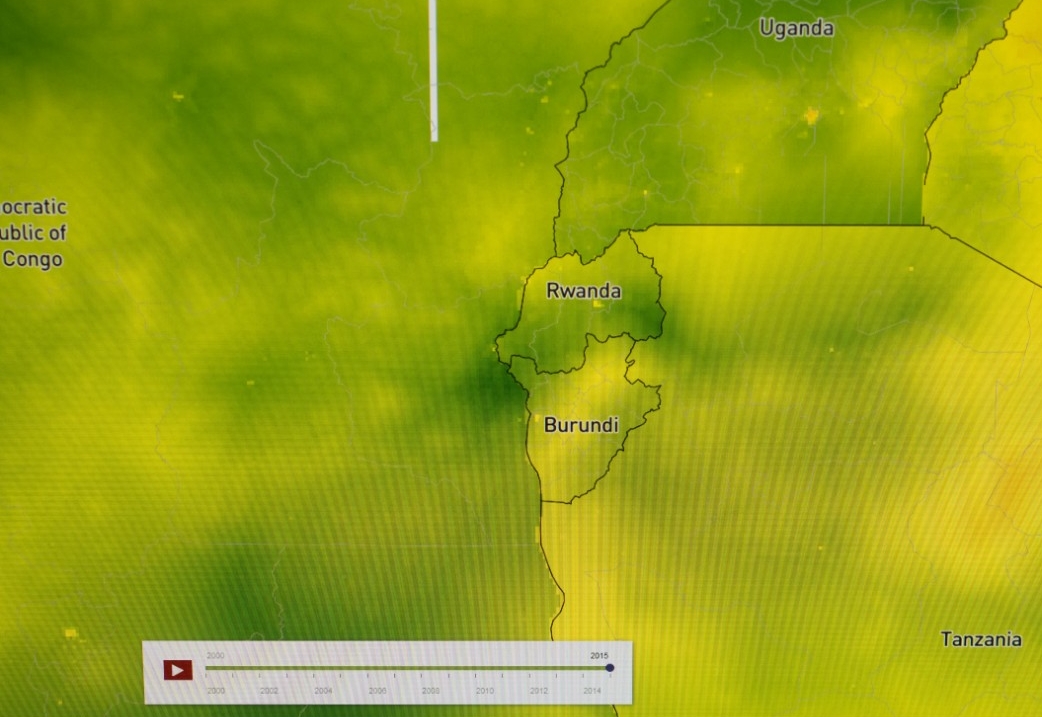

UC student Hana Kim compared two countries in Africa, Rwanda and Burundi. In Rwanda, the incidence of malaria was comparatively low but the use of bed nets was comparatively high. In Burundi, where malaria is a far bigger problem, Kim found fewer people used bed nets to prevent infection. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Kim’s research used demographic and health surveys to identify and map the lowest rates of bed-net use.

Kim examined 10 African nations that had the highest rates of malaria. She collected survey data from nearly 100,000 households with at least one child under 5 years of age in those countries. The surveys revealed that while 68 percent of households reporting having a bed net, just 36 percent said they regularly used them to protect their children.

Most countries will be able to achieve their stated goal of distributing bed nets to at least 80 percent of their targeted population, Kim said. But they will have to change public attitudes toward the bed nets to reduce malaria infection.

Kim said the use of bed nets has proven to reduce malaria infection by as much as 50 percent for children under 5. Mortality rates were reduced as well. Despite the widely known benefits and availability of bed nets, comparatively few people use them.

“Bed nets are a very good strategy to prevent mosquito bites. They’re durable and last a long time compared to mosquito sprays that are not as effective or long-lasting,” she said.

UC geography student Hana Kim mapped the prevalence of malaria across 10 countries, including Burundi and Rwanda. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Kim examined two East African countries in particular: neighbors Rwanda and Burundi. In Rwanda, malaria is prevalent in just 2 percent of children under age 5. But 55 percent of parents surveyed said the regularly protected their sleeping children with bed nets. By comparison, while malaria affects 38 percent of the child population of Burundi, just 18 percent of parents there reported using bed nets.

The UC study found some correlations in the socioeconomics of the 10 countries examined. With a few exceptions, urban residents were more likely to use them. And wealthier parents were more likely to use bed nets, at least in countries where bed nets were not commonly used.

Researchers also found that households with two or more children were far more likely to use bed nets to protect them.

“Our hypothesis is parents with multiple children have more experience with malaria so they realize how important using a bed net is,” Cuadros said. “Young mothers don’t have that experience. And they see an economic opportunity to sell them, even if it’s just for a couple dollars.”

Featured image at top: UC geography graduate student Hana Kim holds a bed net to the sky outside Braunstein Hall. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

UC student Hana Kim grew up sleeping under a bed net in South Korea. She is investigating the reasons why more parents aren't using them to protect sleeping children. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

1819 makerspace transforms into innovation boot camp

January 21, 2025

Kinetic Vision selected the Ground Floor Makerspace at UC’s 1819 Innovation Hub as the perfect place to provide Bearcat co-ops with advanced engineering skills.

Cincy Cyber Week and Microsoft OpenHack take over 1819...

January 17, 2025

UC’s 1819 Innovation Hub was packed with innovative expertise in December during high-profile events like Cincy Cyber Week and a Microsoft Azure OpenHack.

Baylee Schmitt crocheted the childhood bedroom she shared with...

January 17, 2025

UC employee Baylee Schmitt featured in The Boston Globe for her art works made out of yarn.. Schmitt earned her master’s of fine arts degree at Miami University and now manages the University of Cincinnati printmaking lab at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning (DAAP) and teaches there as well.