Unheralded UC alum helped NASA reach moon

Physicist George Sherard Jr. was one of the many African American experts who contributed to the U.S. space race

The NASA factory responsible for making lunar rockets and landers in the 1960s reserved parking spots by name for dignitaries such as Edwin Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins.

And George Sherard Jr.

Unlike the others, Sherard never made it to the moon. But the physicist and University of Cincinnati alumnus contributed to the famous Apollo 11 mission 50 years ago.

Sherard was one of many African Americans who played crucial but unheralded roles in the space program. He worked on Apollo’s guidance and navigation systems as a contractor for Rockwell International. At the California manufacturing plant, Sherard trained astronauts to deal with every conceivable mission failure in simulations. His vaunted position came with some perks.

University of Cincinnati graduate George Sherard Jr. contributed to every Apollo mission but did not seek fame. Pictured is his Walnut Hills High School class photo. Provided

“I got a parking space right beside the astronauts. My name was right alongside theirs,” Sherard said. “We would plan the entire trip to the moon.”

Sherard passed away in 2003. But Joan Thomas, a family relative by marriage, interviewed Sherard at length in 2000 to capture for posterity his perspective on this exciting time in American history.

“I don’t know that it was advertised, but there were quite a few blacks involved in the mission,” Sherard said. “Many of them were involved in the construction of the lunar module built in Downey, California. I was given permission to get as many people into the Apollo mission as I could, regardless of race or color.”

Thomas recorded two interviews with Sherard in the public radio studios in Atlanta and Cincinnati’s WVXU.

“I liked him immensely when I met him. I was in awe of his accomplishments — what a trailblazer he had been,” Thomas said.

Thomas interviewed Sherard long before Margot Lee Shetterly’s book “Hidden Figures” was published in 2016. That book profiled the African American women who worked as NASA mathematicians and whose precise calculations were essential to every Apollo mission.

Like the people profiled in that book, Sherard made his contributions to Apollo seem almost ordinary.

“It was obviously an important mission. It was something that had never been done before,” Sherard said.

The interviews with Sherard have never been broadcast or published. With the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, Thomas reached out to UC and the Smithsonian Institution to share Sherard’s story.

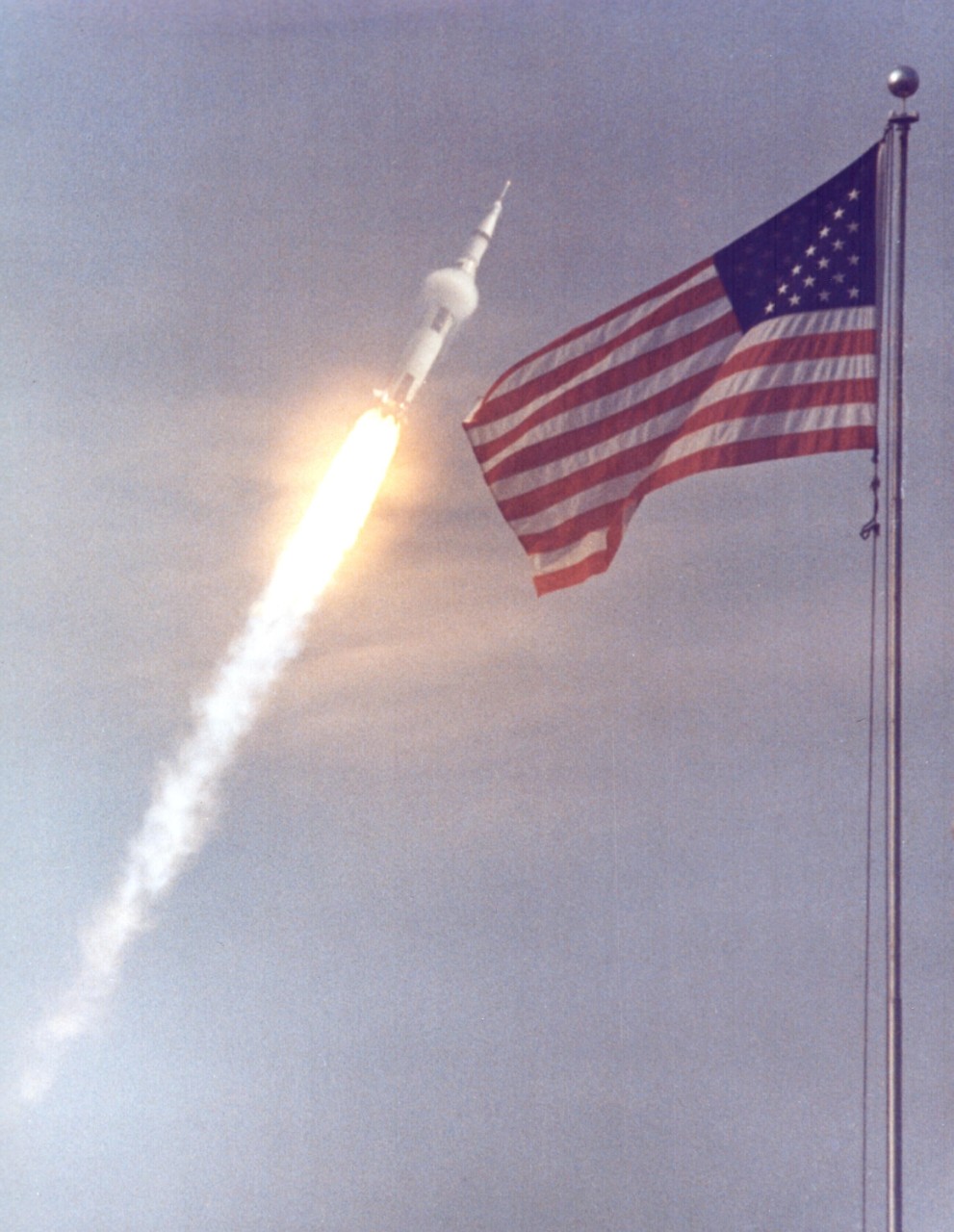

Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon, a feat accomplished by just 11 other people. After leaving NASA, Armstrong taught aerospace engineering at UC between 1971 and 1979. Photo/NASA

“I thought he was amazing. I didn’t want (his story) to die on a file on my computer,” she said.

UC has a storied connection to NASA through Armstrong. After setting foot on the moon during Apollo 11, Armstrong left NASA to teach aerospace engineering at UC from 1971-79. He inspired generations of UC students to pursue careers in aviation and aerospace.

During his long career, Sherard encountered racism in ways big and small. Despite his demonstrated proficiency in the subject, his high school guidance counselor told him to give up his dream to become a physicist and instead pursue a trade, like printing.

It was obviously an important mission. It was something that had never been done before.

George Sherard Jr., UC graduate and physicist

While serving a prestigious fellowship at an Ivy League school, Sherard was given menial tasks instead of teaching undergraduates like other fellows there. Once during a blizzard at an airport in the early 1960s, he and other African American travelers were sequestered at the same table of a public dining room. And Sherard said a professor at another Ivy League university nearly failed him in an exam in which his white study partner received top marks for virtually identical work.

Apollo 11 blasts off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, for its 239,000-mile trip to the moon. Photo/NASA

Sherard was born the son of a minister in Fitzgerald, Georgia, in 1918. His mother tragically died a month later so Sherard spent his infancy in the care of his grandmother. After his father remarried five years later, Sherard joined them outside Maysville, Kentucky, perhaps most famous for being the hometown of singer Rosemary Clooney.

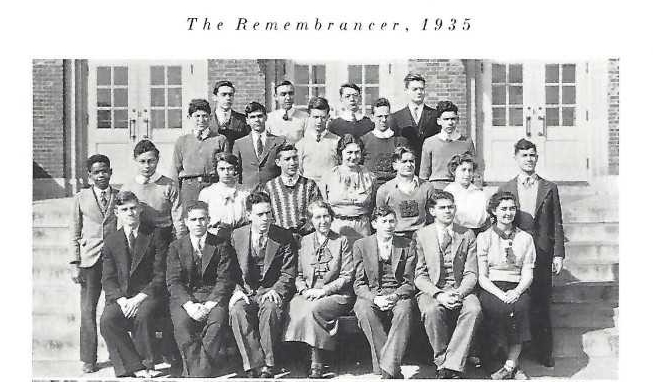

His father moved from parish to parish around the Midwest, eventually coming to Cincinnati where Sherard attended Walnut Hills High School and took college preparatory classes. He belonged to the debate club and the camera club — ironic since photos of Sherard are hard to find today. He told Thomas he didn’t even have a photographer at his wedding.

At UC he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics with honors in 1940 as a special scholar. He was studying for his doctorate at UC when World War II erupted. His advisors urged him to complete a master’s degree immediately to prevent the looming wartime draft from interfering with his academic advancement. Specializing in acoustics, Sherard submitted a thesis in 1942 on measuring the velocity of sound in solids.

Upon graduation, he worked as an acoustician for the Signal Corps Laboratories in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. After a short stint as a professor at Clark College in Georgia, he stopped at Howard University to visit his mentor at UC, Herman Branson. Branson was just the fifth African American in the United States to receive a Ph.D. and contributed to Linus Pauling's Nobel Prize-winning research into the Alpha Helix.

“He put a piece of chalk in my hand and asked me to explain to some undergraduate students how a wheatstone bridge operated,” Sherard said of the type of electrical circuit. “I put down the chalk three years later.”

Sherard spent three years teaching at Howard, but his passion was in aviation. As a grade schooler, his imagination was fired by Charles Lindbergh’s famous 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, and his hero’s welcome in Paris.

UC graduate George Sherard Jr., pictured far left, was in the Senior Debate Club at Walnut Hills High School. Photo/Provided

Sherard joined aerospace company Rockwell International, which was contracted to develop the Apollo missions. Sherard worked on all six missions, including the one that landed Armstrong and Aldrin on the moon.

Sherard recalled the stress and panic of the 1970 ill-fated Apollo 13 mission, in which an explosion damaged the spacecraft and threatened the lives of the three astronauts more than 200,000 miles from Earth. The astronauts relied on Sherard and countless other experts from NASA to solve problems ranging from a toxic buildup of carbon dioxide in the capsule to powering up the command module.

“We worked around the clock without a thought of going home and getting rest. We’d eat in the cafeteria, brush our teeth in the bathroom and carry on,” Sherard said.

NASA’s monumental rescue effort became a celebrated moment of American ingenuity and determination. The line “Houston, we have a problem” from the Hollywood blockbuster “Apollo 13” is still a household phrase. The three astronauts safely splashed down in the Pacific Ocean after their abbreviated six-day mission.

After the Apollo missions, Sherard returned to Cincinnati to work for General Electric Aviation. He married his former UC classmate, Emma. A classical pianist, Sherard and his wife were patrons of local orchestras in Cincinnati.

“I like music very much. It’s been a part of my life wherever I was. I was always playing for the church,” he said.

I think he had a quiet, dogged determination. You had to in an era like that.

Joan Thomas, Interviewer talking about George Sherard's aerospace career during the 1960s

Interviewer Joan Thomas. Photo/Provided

Sherard worked on the AGM-28 Hound Dog, one of the world’s first cruise missiles, as well as an experimental nuclear-powered jet aircraft, which was scrapped as unsafe and impractical. He finished his career developing the B-2 stealth bomber.

Over the years, Sherard rubbed elbows with luminaries such as fellow physicist Albert Einstein. Sherard played host to Einstein twice at speaking engagements at Howard University.

“He was quite a down-to-earth person,” Sherard said. “His accent was severely German. It was guttural and he was difficult to understand. One thing that impressed me, though. He was very interested in helping minority people get an opportunity in technical fields. This impressed me quite a bit.”

During a chance encounter in Philadelphia, Sherard struck up a lifelong friendship with Tom Bradley, who would become the first African American mayor of Los Angeles.

“I and his other friends encouraged him to run. The first time, he lost. The second time, he won by a landslide and he was reelected quite a few more times,” Sherard said.

Interviewer Thomas said Sherard’s career success is a tribute to his strong character in the face of adversity.

“I think he had a quiet, dogged determination. You had to in an era like that,” she said.

But Sherard said his experiences never made him bitter. Quite the contrary, he said.

“My life has been really enjoyable,” Sherard said. “I have no regrets.”

UC aerospace engineering professor Mark Turner celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 launch by wearing a commemorative T-shirt and showing off his Lego lunar capsule. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Service

UC celebrates Apollo 11

The University of Cincinnati's Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics will celebrate the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and the department's 90th anniversary with a weekend of events Aug. 29-31 called the Next Giant Leap.

UC will host a panel discussion on "Human Space Exploration – from Apollo to Mars." James Hansen, author of the Neil Armstrong biography "First Man," will give the keynote during a dinner.

Registration and ticket information are available here.

UC's storied space history

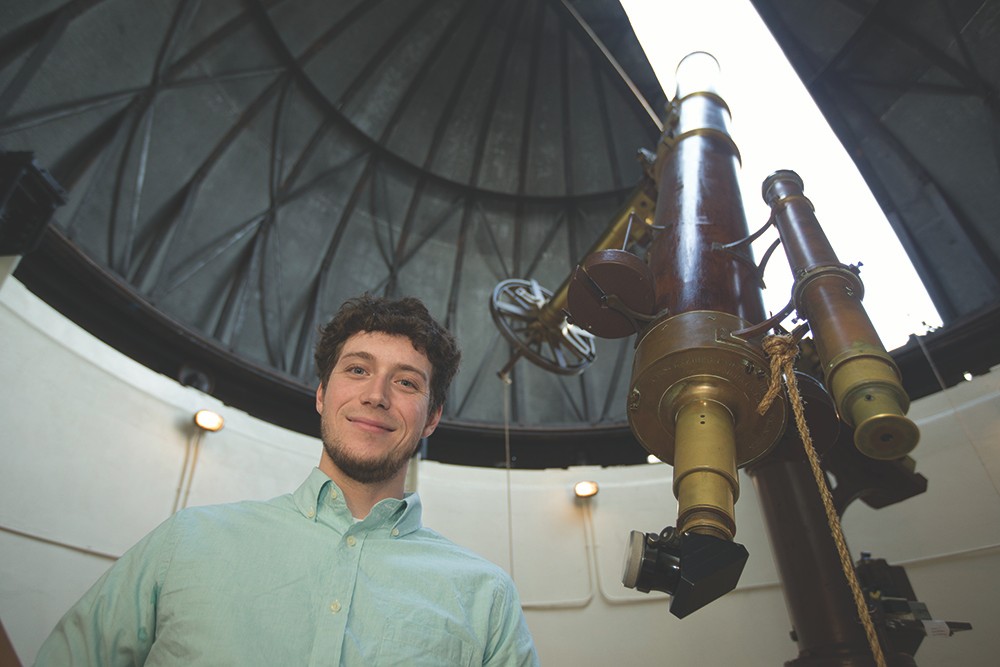

Many University of Cincinnati students have pursued the stars. UC took over the Cincinnati Observatory in 1871. The Physics Department’s historic telescopes on Mount Lookout are visited by thousands of people each year.

After the Soviet Union launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, UC responded by establishing the Institute of Space Sciences, the first school of its kind in the United States dedicated to space exploration. The institute helped NASA refine lunar orbiting in preparation for the Apollo missions and later merged with UC’s Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics.

Today, many UC graduates continue to work in the aerospace industry through employers such as NASA, Boeing, SpaceX and the industry’s many contractors, UC Physics Department Head Leigh Smith said.

UC graduate Howard Dunholter helped build the Atlas booster and Centaur hydrogen-oxygen rocket stage for General Dynamics Corp. He was enshrined in the Wall of Honor at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

“A lot of UC students end up working for the Air Force and the aerospace industry,” Smith said. “About 30 percent of our physics undergraduates are in astrophysics.”

One of those graduates, Kevin Wagner, is looking for exoplanets in distant galaxies. Others are working for aerospace companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin.

What's exciting is our students are really ready to make the next 'giant leap.'

Mark Turner, UC aerospace engineering professor

UC professor Mark Turner has spent his career conducting aerospace engineering research in collaboration with agencies such as NASA. He recalled a recent visit to SpaceX to see one of his former students working there.

“Elon Musk had a larger cubicle than anyone but no door. And he had a picture of Mars posted there. That was his vision,” Turner said. “What’s exciting is that our students are really ready to make the next 'giant leap.'”

Turner said the space industry has led to countless technological advancements people take for granted every day, from satellite TV and radio to navigation services.

“What’s amazing to me is how many disciplines are involved and how many people are impacted by what they’ve done,” he said. “It’s not just Neil Armstrong landing on the moon. We use GPS in our cell phones every day.”

Turner said he is confident that incoming UC students will be next to help expand our reach to Mars and beyond just as Sherard and his peers looked at the Apollo missions as an inevitable success.

“This amazing feat was just expected. I think our students will end up having the same attitude – of course, we can do it,” Turner said. “And no doubt they will.”

UC grad Kevin Wagner poses at the Cincinnati Observatory. Wagner is searching for exoplanets or planets outside our solar system. In 2016, he and his research team thought they found one, but additional research now indicates it may be a star. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Creative Services

More on UC's ties to space exploration

UC mountaineer, galactic explorer

After Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, he taught engineering at UC

Featured image at top: The Earth rises over the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. Photo/NASA

Next Lives Here

Discover UC's commitment to Next Lives Here, the strategic direction with designs on leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.

Become a Bearcat

Do you want to take the world's next 'giant leap?' UC can help you do it. Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100. Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

UC celebrates record spring class of 2025

May 2, 2025

UC recognized a record spring class of 2025 at commencement at Fifth Third Arena.

UC students recognized for achievement in real-world learning

May 1, 2025

Three undergraduate University of Cincinnati Arts and Sciences students are honored for outstanding achievement in cooperative education at the close of the 2024-2025 school year.

‘Doing Good Together’ course gains recognition

May 1, 2025

New honors course, titled “Doing Good Together,” teaches students about philanthropy with a class project that distributes real funds to UC-affiliated nonprofits. Course sparked UC’s membership in national consortium, Philanthropy Lab.