Baby spiders really are watching you

The vision of spiderlings is nearly as keen as their parents, according to University of Cincinnati biologists

Baby jumping spiders can hunt prey just like their parents do because they have vision nearly as good, according to a University of Cincinnati study.

The study, published in the journal Vision Research, helps explain how animals the size of a bread crumb fit all the complex architecture of adult eyes into a much tinier package.

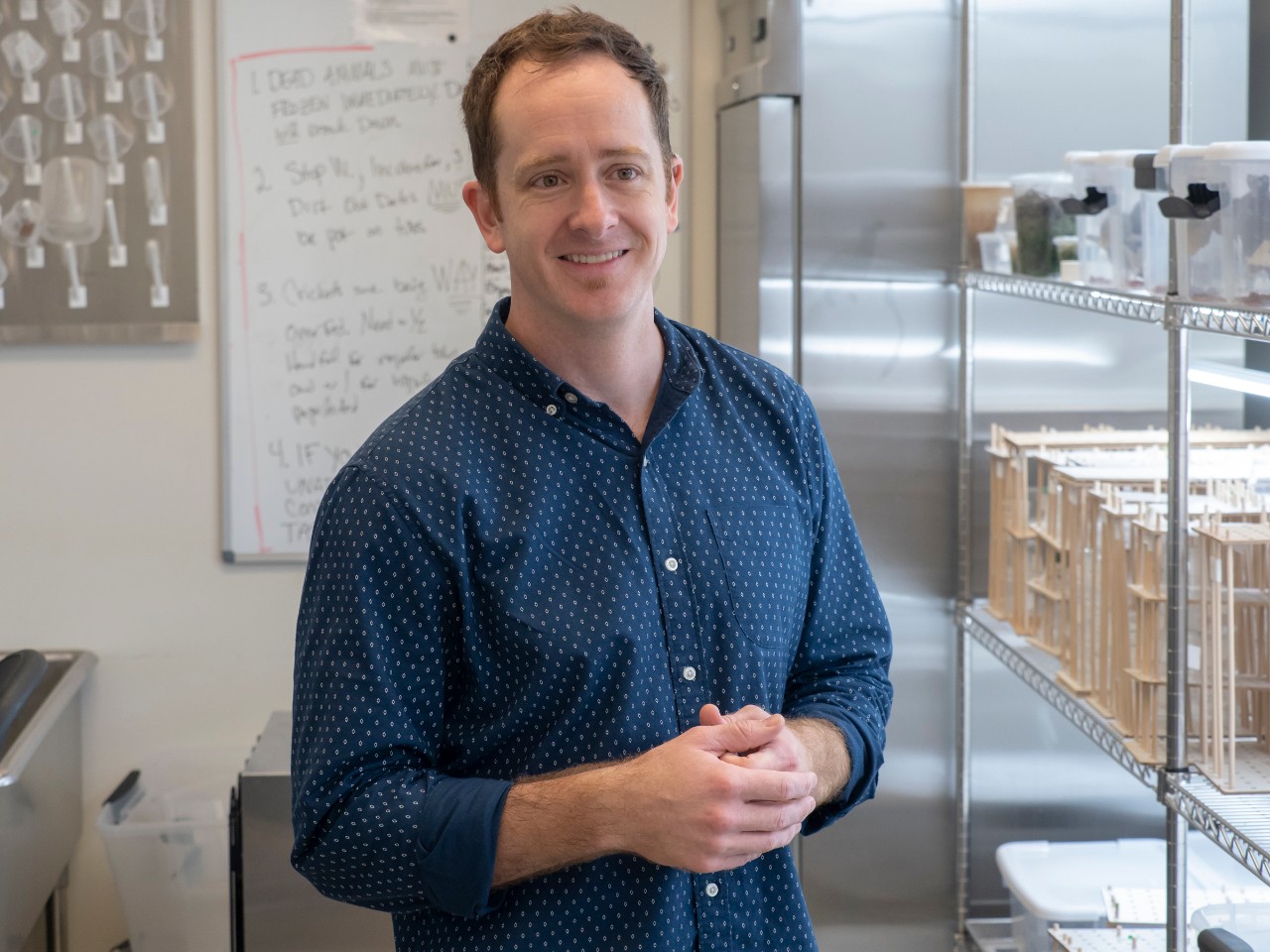

“Spiderlings can adopt prey-specific hunting strategies. They can solve problems. They’re clever about navigating their environment,” said Nathan Morehouse, a UC assistant professor of biological sciences. “This suggests their eyes are providing as much high-quality information when they’re small as when they’re large. And that was a puzzle.”

Morehouse worked on the study while he was teaching at the University of Pittsburgh. UC biology professor Elke Buschbeck also co-authored the journal article.

“We thought the adults were pressing the limits of what was physically possible with vision. And then you have babies that are a hundredth that size,” Morehouse said. “That makes us wonder how they’re accomplishing all of this?”

Baby jumping spiders can see nearly as well as their much bigger parents. Photo/Daniel Zurek

John Thomas Gote, a Pitt graduate and the study’s lead author, said vision develops far differently in spiders compared to people.

“For humans, it takes three to five years before babies can reach the visual acuity of adults,” Gote said. “Jumping spiders achieve this as soon as they exit the nest.

“What intrigued me most was learning about just how well jumping spiders could see, despite their incredibly small size,” Gote said. “For example, cats and jumping spiders can see the world in surprisingly similar detail.”

The research found that baby spiders have the same number of photoreceptors as adults but packed differently to fit in a smaller space. These 8,000 photoreceptors are smaller than those found in the adults. And many of these cells are shaped like a long cylinder to fit more of them side by side to maintain the visual acuity that helps spiders distinguish objects at a distance.

With good science and hard work, insights can come from anywhere. Undergraduates can be part of meaningful, world-class research.

Nathan Morehouse, UC biologist

Morehouse said it’s not just the number but the placement of these photoreceptors in the eyes that help an animal make sense of its world.

“If you have a photoreceptor spaced every 5 degrees, you’ll only see things that are more than 5 degrees apart. But if they’re 1 degree apart, you can distinguish things that are closer together,” he said.

Humans can distinguish objects less than .007 degrees apart.

“We’re some of the best at this in the animal kingdom. We can tell something a meter apart more than a kilometer away,” Morehouse said.

So if you looked down from the top of the Eiffel Tower, you could easily tell a person’s hat from their belt, he said.

“The spiderlings are two orders of magnitude smaller than the adults. Yet they’re still capable of all of this very complicated behavior,” Morehouse said.

UC biologist Nathan Morehouse is studying the vision of jumping spiders around the world. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Many jumping spiders have extraordinary vision, such as tetrachromacy, the ability to see four colors (ultraviolet, red, blue and green). That’s even better than our typical trichromatic vision that limits most of us to seeing variations of red, green and blue. Scientists are investigating whether some people see even more colors.

UC researchers used their custom-made micro-ophthalmoscope, similar to those used eye doctors, to peer into the tiny eyes of baby spiders.

“The hardest part is to handle these tiny, fragile creatures with utter care as to not harm them while measuring them,” UC’s Buschbeck said.

Building and refining her lab’s micro-ophthalmoscope took years of work, she said.

“It’s a powerful, one-of-a-kind research tool that allows us to engage in several exciting projects that were not possible before,” she said.

Researchers used the equipment to map the light-sensitive cells and their relationship.

“We knew the angular distance between photoreceptors to understand the spatial acuity of eyes or how the spiders can see patterns in the world and distinguish objects,” Morehouse said.

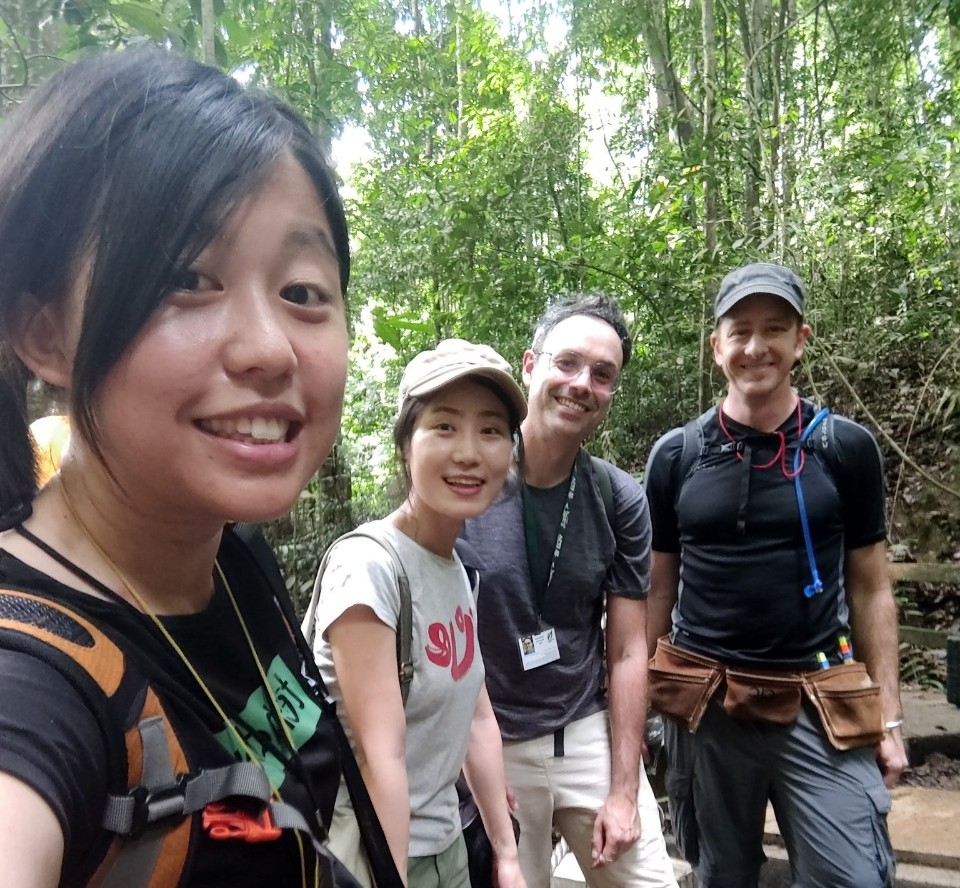

UC biologist Nathan Morehouse, far right, is working with researchers from six other countries on a three-year field project to study jumping spiders around the world. Follow their progress on Twitter and Instagram at #SeeingColorEvolve. Photo/Provided

They also conducted a microscopic analysis or histology of the spider eyes. Like most creatures in the animal kingdom, jumping spiders begin life with eyes that are much larger in proportion to the rest of their bodies.

“And the bigger the eye, the better it functions. The more light it captures and the more in focus objects are,” Morehouse said. “So one strategy is to start life as close to your adult eye size as you can.”

This growth pattern, called negative ontogenetic allometry, explains why some puppies have enormous feet.

“People say, ‘That’s going to be a big dog’ because of the size of the puppy’s feet. A puppy grows into its feet in the same way that jumping spiders grow into their eyes,” Morehouse said.

Arguably, the large eyes also make baby animals look darn cute, he said. And the fuzzy little jumping spiders with their solicitous, upturned postures already have that going for them, according to some Twitter fans.

Twitter is full of tweets about the cuteness of jumping spiders.

One drawback of baby spiders’ eyes is they capture less light than those of the adults. That means they can’t see as well in dim conditions. This makes baby spiders conspicuous to field researchers working in the dark understory, he said.

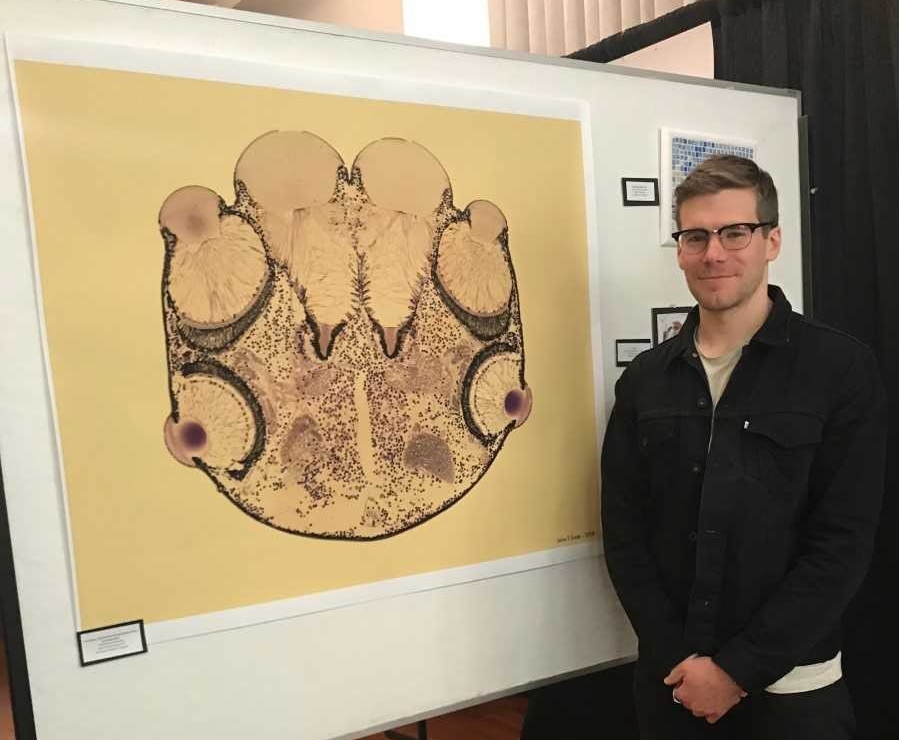

University of Pittsburgh graduate John Thomas Gote stands next to a poster depicting the photoreceptors of baby jumping spiders. Pitt postdoctoral researcher Daniel Zurek and student Patrick Butler also contributed to the study. Photo/Provided

“One thing you pick up on is spiderlings act a little drunk. They’re a bit stumbly,” he said. “They seem a little impaired. And it’s probably because the world is a little dimmer, like you’re walking through the house with the lights off bumping your shins on the furniture.”

Both Morehouse and Buschbeck credited Gote for his hard work on the study at Pitt. Gote completed the project while finishing his undergraduate studies.

“Growing up, I never really considered myself as a spider enthusiast, but it didn’t take long before I was hooked,” Gote said.

“I feel very privileged to have been able to work with this research team,” Buschbeck said.

Morehouse said UC also encourages and fosters undergraduate research as a Carnegie-ranked research institution.

“With good science and hard work, insights can come from anywhere. Undergraduates can be part of meaningful, world-class research,” Morehouse said.

UC biologist Nathan Morehouse is collaborating with an international team of researchers to study jumping spiders around the globe. Here the team treks into the rainforest in Singapore. Photo/Nathan Morehouse

Meanwhile, Morehouse is working on a related project on jumping spiders around the world. Sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the project took him and his international team of collaborators to Singapore this summer. Researchers collected more than 800 spiders and recorded data on their many diverse habitats for the vision study.

The team's international passports. Photo/Nathan Morehouse

“It was a massive success,” Morehouse said. “We encountered at least three species brand new to science. And we found described species for which there were no previous records in Singapore.”

The researchers are studying jumping spiders to understand global biodiversity and the evolution and development of color vision. The project is expected to take researchers to South Africa later this year and then to Australia and Colombia.

“These field excursions are wonderful, but it’s just the tip of the iceberg. It means my team has three months of work here,” he said.

You can follow the team's fieldwork on Twitter and Instagram at #SeeingColorEvolve.

Featured image at top: A jumping spider in UC's Morehouse Lab. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC research in the news

Scientific American: Baby jumping spiders see surprisingly well

Inside Ecology: Baby jumping spiders really are watching you

Mother Nature Network: Baby spiders are born with big eyes

Next Lives Here

Discover UC's commitment to Next Lives Here, the strategic direction with designs on leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.

Become a Bearcat

Do you like the idea of conducting your own biology research? Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100. Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

UC celebrates record spring class of 2025

May 2, 2025

UC recognized a record spring class of 2025 at commencement at Fifth Third Arena.

UC students recognized for achievement in real-world learning

May 1, 2025

Three undergraduate University of Cincinnati Arts and Sciences students are honored for outstanding achievement in cooperative education at the close of the 2024-2025 school year.

‘Doing Good Together’ course gains recognition

May 1, 2025

New honors course, titled “Doing Good Together,” teaches students about philanthropy with a class project that distributes real funds to UC-affiliated nonprofits. Course sparked UC’s membership in national consortium, Philanthropy Lab.