UC grad puts DNA to work for wildlife

Alumna Heather Farrington is applying skills she learned at UC to the Cincinnati Museum Center's new genetics lab

A University of Cincinnati graduate oversees the new state-of-the-art genetics lab that opened this year as part of the Cincinnati Museum Center’s $228 million renovation.

Heather Farrington earned her doctorate in biological sciences from UC, where she charted the family trees of Galapagos finches and used the latest DNA analysis to gain fresh insights into century-old museum specimens.

Today, Farrington is applying skills she learned at UC to her role as the museum’s curator of zoology. She organizes exhibits, maintains its vast behind-the-scenes collection and supervises the new genetics lab in the museum at Cincinnati’s Union Terminal.

The lab works with researchers and government agencies on a variety of projects that require DNA analysis, from conserving wildlife to improving our understanding of the natural world.

“Coming to UC really changed my career path,” she said.

The Cincinnati Museum Center opened a new DNA lab at Union Terminal. The lab has glass windows that allow the public to see research in action. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Farrington was looking for a graduate program in aquatic ecology that could satisfy her growing curiosity about genetics. UC biology professor Kenneth Petren, who at the time was dean of UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences, reached out to recruit her to UC.

“He said, ‘Well, I do genetics, but I don’t do fish. I work on Darwin’s finches,’” Farrington said.

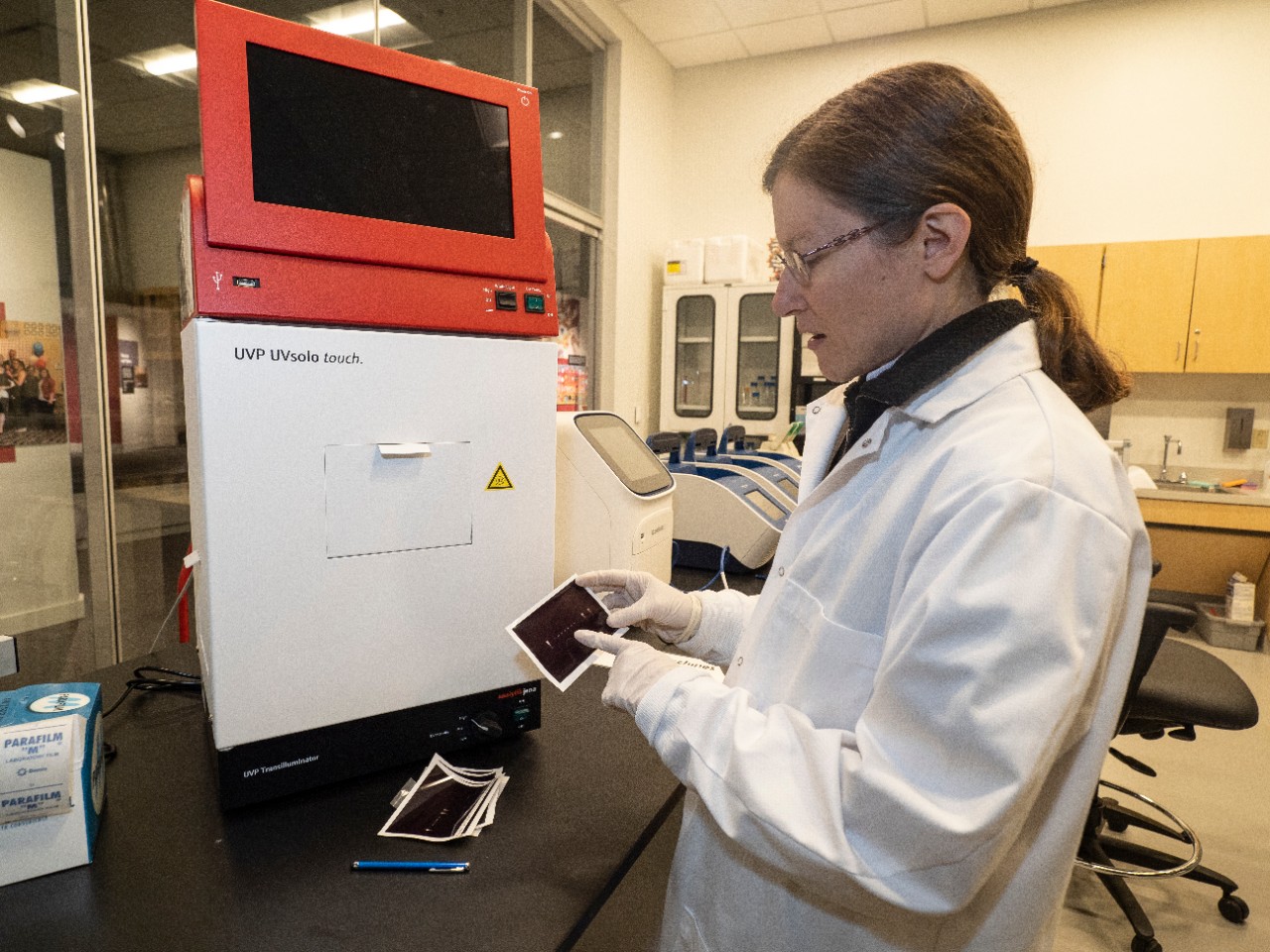

UC graduate Heather Farrington works as curator of zoology for the Cincinnati Museum Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

At UC, Petren has conducted two decades of research on descendants of birds that shaped Charles Darwin’s understanding of evolution through natural selection in the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador.

“I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, I can’t say no to Darwin’s finches,’” Farrington said.

Farrington, Petren and UC biology professor Lucinda Lawson authored a study of finch populations that was published recently in the journal Conservation Genetics. Moreover, at UC Farrington also realized what a valuable resource museum collections are for genetic research. For her dissertation, she examined museum specimens gathered more than 100 years ago to understand how Galapagos finch populations have changed over time.

Museum collections manager Emily Imhoff explains how she and zoology curator Heather Farrington identify strands of DNA using the lab equipment. The lab has worked on several wildlife conservation projects. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Farrington developed many of the important lab techniques she uses at the museum while conducting research at UC between 2004 and 2011, Petren said.

“While at UC, Heather worked very hard to pioneer the use of museum specimens for population genetics analysis,” Petren said. “Our lab was a leader in this field because of Heather’s efforts.

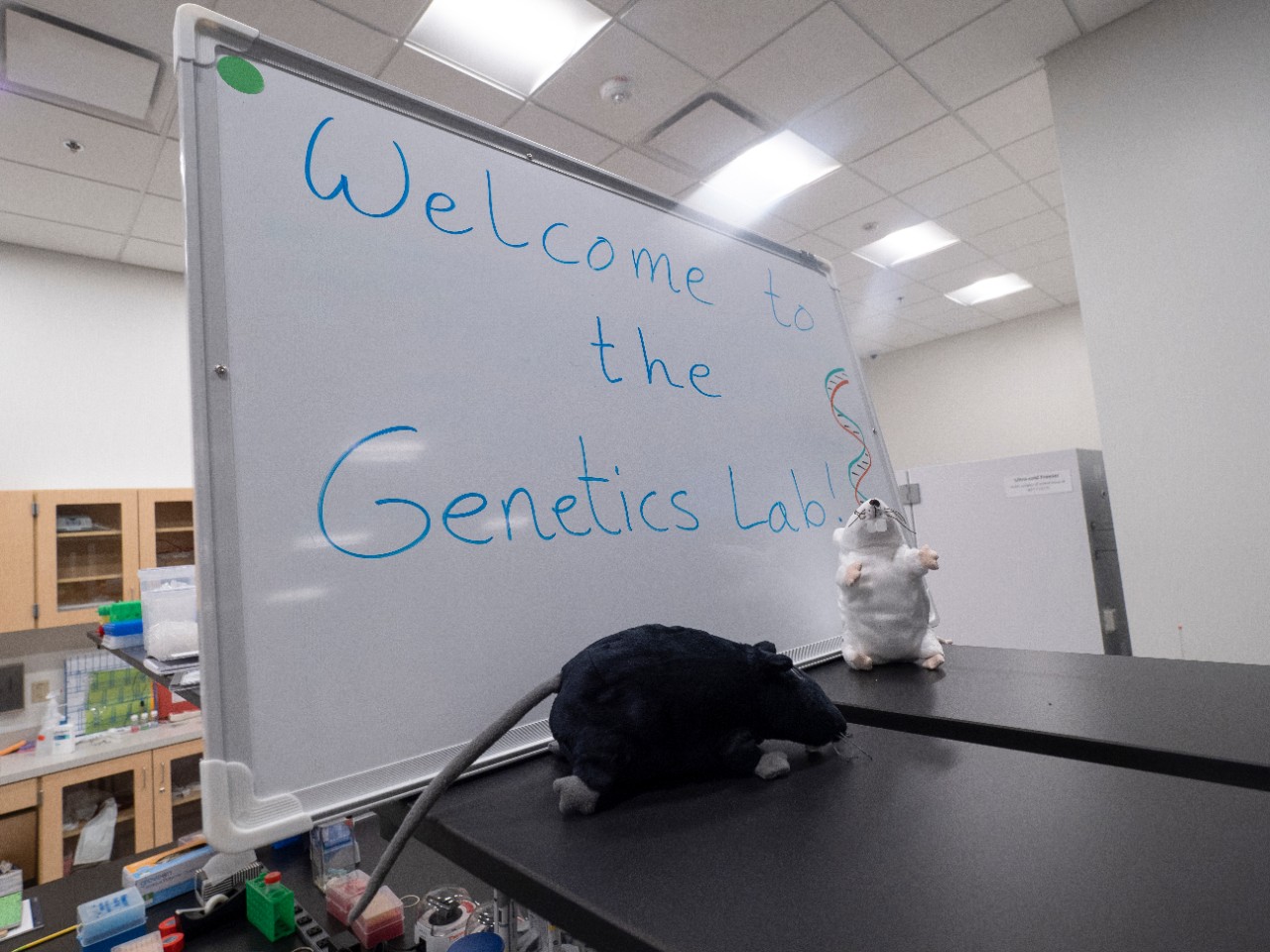

UC graduate Heather Farrington oversees the new genetics lab at the Cincinnati Museum Center in her role as curator of zoology. Pictured are the lab's mascots, plush rats named Gene and Helix. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

“She used the techniques she developed to address issues of conservation in several different species of Galapagos finches,” Petren said. “She went on to become a leader in the field of environmental DNA in her role working for the U.S. Department of Defense, which was interested in monitoring rare species, or to provide early warnings of problematic invasive species like the Asian carp.”

The museum’s DNA lab has glass walls on two sides so the public can watch scientists at work. Next door, visitors also can watch museum staff and volunteers prepare fossils from a public gallery at the paleontology lab. Both labs use whiteboards and labels to educate visitors. But only the genetics lab has two mascots, fluffy plush rats named Gene and Helix.

We definitely feel our work is useful when we take on projects with other researchers. Heather and I are both passionate about our work.

Emily Imhoff, Cincinnati Museum Center collections manager

Farrington’s colleague, museum collections manager Emily Imhoff, explained how the sensitive equipment works.

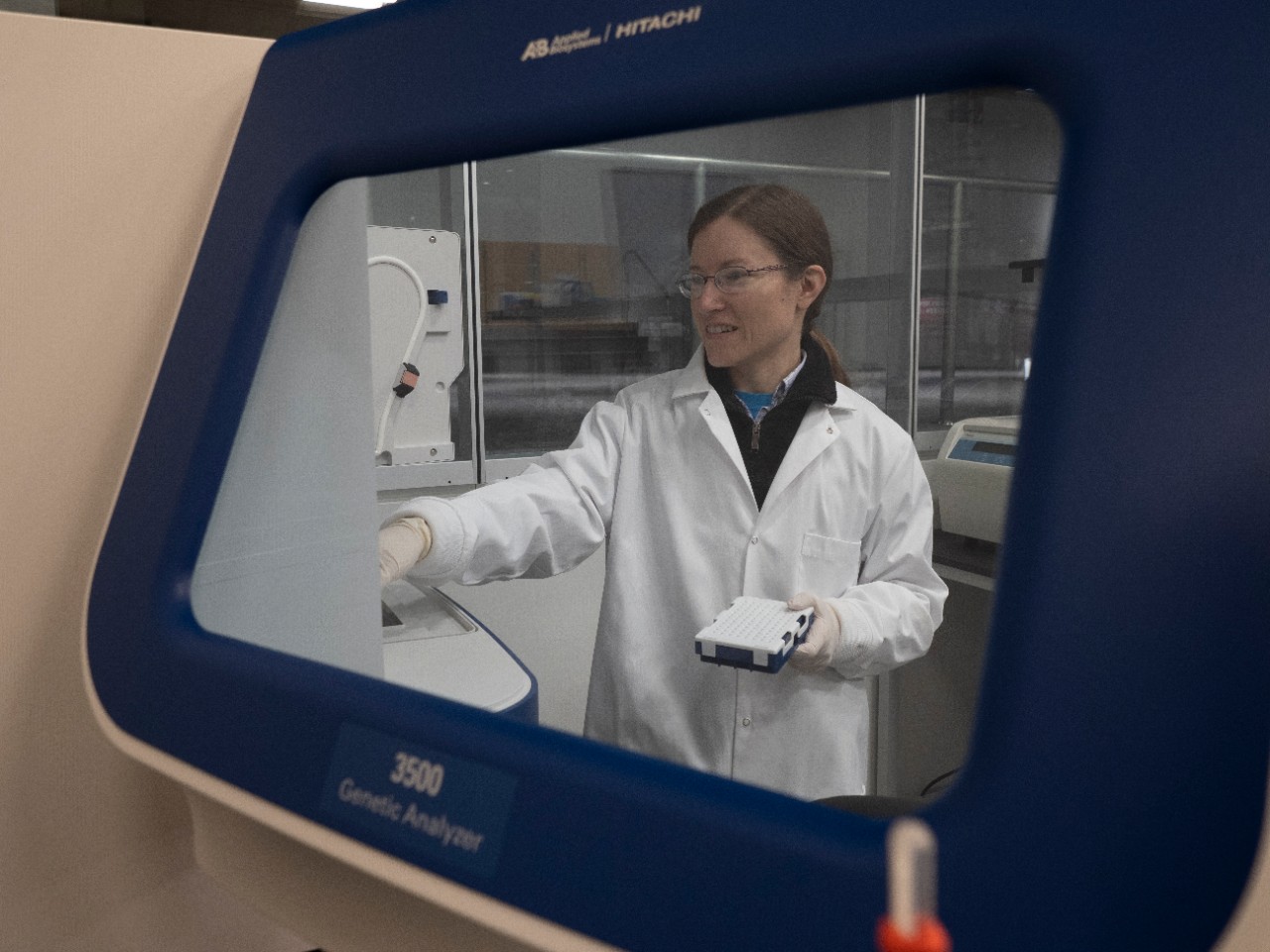

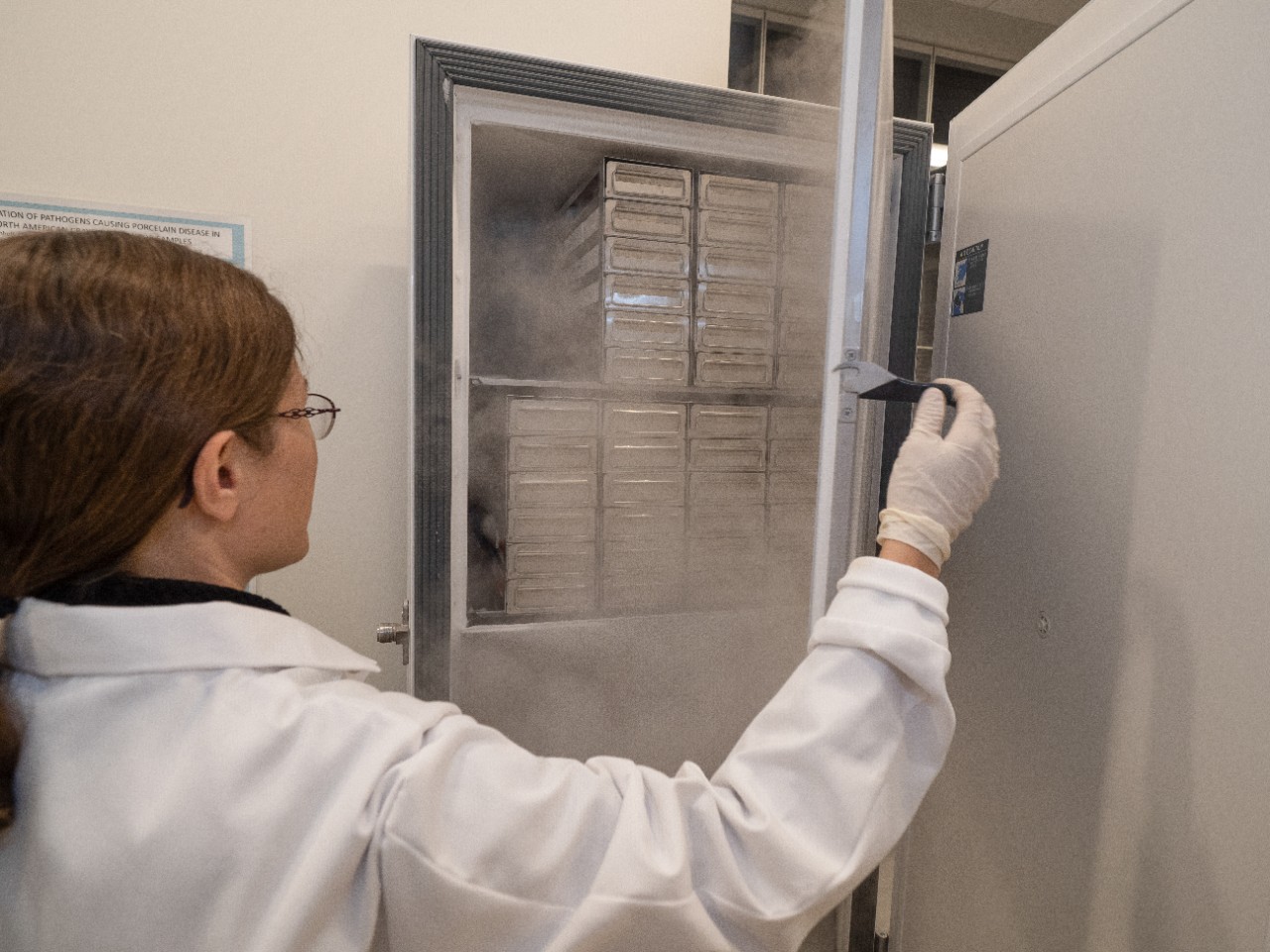

The lab keeps DNA samples in refrigerators, including one set to a chilly minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit. Scientists can identify the concentration of DNA, amplify the sample and sequence it to understand the lineage and relationships of species.

Recently, the museum’s lab has worked on conservation projects such as saving the Allegheny woodrat, a small rodent that is in decline from Indiana to New Jersey. In Ohio it’s found in only one place, the Edge of Appalachia Preserve about two hours southeast of UC. The lab analysis found that Ohio’s woodrats are maintaining their genetic diversity so far despite their geographic isolation, Imhoff said. She also has studied the genetics of Ohio’s crayfish and a beautiful yellow-and-black songbird called a hooded warbler.

Museum collections manager Emily Imhoff is viewed through the glass door of a genetic analyzer. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

“We definitely feel our work is useful when we take on projects with other researchers,” Imhoff said. “Heather and I are both passionate about our work.”

Farrington also manages the behind-the-scenes collection at the museum’s enormous Geier Collections and Research Center, a nondescript building known for the family of woolly mammoth sculptures standing watch along Fifth Street. Here the museum stores many of its scientific and historic collections — a vast menagerie of preserved mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and insects.

The Cincinnati Museum Center stores off-exhibit and research specimens at its Geier Research Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The warehouse-sized space holds shelf after shelf of taxidermy specimens: African lions, Bengal tigers, enormous moose and diminutive antelope along with an ark of rarities such as armored animals called pangolins, a scaly anteater. A fierce golden eagle with its wings spread wide sits next to a beautiful bird of paradise showing off its feathered finery on a branch.

Some specimens are hunting trophies such as bearskin rugs that were donated through bequests or estates. While they don’t necessarily make good museum displays, Farrington said, they are valuable for educational and other purposes. Swatches of polar bear fur demonstrate the animal’s extreme adaptations. The fur of the white bears is mostly transparent and is set against black skin that helps absorb the polar sun’s stingy warmth.

“Albinos are always a unique specimen so we have albino squirrels and deer — different examples of leucism and albinism,” she said.

Curator Heather Farrington reaches for a sample of polar bear fur stored with taxidermy mounts at the Geier Research Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Each week volunteers at the museum help prepare new donations of roadkill owls or unfortunate birds that flew into windows. Besides the true-to-life mounts, the museum keeps a vast catalog of individual specimens stored in rows of cabinets for scientific research.

At a table, a volunteer prepared the fanned tail of a pretty yellow-shafted flicker. While many have heard this loud bird calling in Ohio’s woods and suburbs, few people have seen the skittish bird’s colorful, patterned plumage so close.

Artist John James Audubon, the Cincinnati Museum Center's first zoology curator, left Cincinnati to work on his 'Birds of America' folio, including this painting of now extinct Carolina parakeets.

Famed wildlife artist John James Audubon painted his avian subjects from life, capturing their colors, shapes and patterns in exacting detail. Audubon was the Cincinnati Museum Center’s first zoology curator in 1819, the year UC was founded.

“He was here nine months before he started traveling for his ‘Birds of America’ book. I have big shoes to fill,” Farrington said.

Perhaps the museum’s rarest zoology specimen is a large penguin-like bird called a great auk. These flightless seagoing relatives of the puffin were hunted to extinction 20 years before the Civil War. The museum’s specimen might have been the very last living great auk in the world, taken during the last commissioned auk-hunting expedition in 1844. The museum is investigating that question now using genetic testing. The museum acquired the rare specimen in the 1970s. The auk was sold at auction in the mid-1800s from a lot of four specimens that went to museums around the world. Two went to museums in Great Britain.

“One went to Los Angeles. One came here. We’ll have it sampled to see if it indeed was the last known great auk,” Farrington said.

Heather Farrington opens a cabinet to reveal a collection of extinct birds, including the ivory-billed woodpecker, Carolina parakeet, Eskimo curlew and passenger pigeon. Also pictured in the middle is the museum's only taxidermy mount of a rare but recovering Kirtland's warbler. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

But the auk isn’t the museum’s only memento to human folly.

Farrington opened one cabinet drawer to expose a heartbreaking birder’s lament of natural treasures: ivory-billed woodpeckers, Carolina parakeets, passenger pigeons and Eskimo curlews, all lost to time. Most of these specimens came from zoos that tried in vain to save the species.

The Cincinnati Museum Center has several specimens of now extinct Carolina parakeets, the last of which died at the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Among these representatives of human-caused extinction is the museum’s only example of a rare songbird called a Kirtland’s warbler that was destined for the same fate. But among the many birds in the steel cabinet, only the Kirtland’s was alive in 1973 to benefit from the protections of the Endangered Species Act, which saved it from disappearing as well. This month the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared the warbler sufficiently recovered to take off the endangered list.

Today, museums such as the Cincinnati Museum Center play a major role in conserving wildlife. Farrington’s mentors at UC say there is nobody better to oversee that task.

“While she was a graduate student at UC, Heather did an exemplary job conducting research,” said Theresa Culley, head of UC’s Department of Biological Sciences. “She would often go right past the ‘what?’ and dive directly into the ‘why?’ and ‘how?’”

Culley served on Farrington’s thesis committee.

“I view Heather as the perfect person to lead the DNA lab at the Cincinnati Museum Center,” Culley said. “She is an integral link in UC‘s association with the center and a key player in the college’s recent initiative to promote science engagement with our partners in the community.”

Farrington said her experience while researching museum specimens for her dissertation at UC convinced her of how valuable these resources can be for future study.

“That is really what got me into museum work and the amazing things you can learn from museum specimens,” Farrington said.

Featured image at top: Heather Farrington poses in front of the mammoth sculptures outside the Cincinnati Museum Center's Geier Collections and Research Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Cincinnati Museum Center volunteers help prepare tissue samples and scientific specimens at the Geier Research Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The Cincinnati Museum Center's Darry Whitsett works on tissue samples at the Geier Collections and Research Center. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Cincinnati Museum Center collections manager Emily Imhoff points to a display screen in the museum's genetics lab. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The genetics lab keeps samples in a freezer that maintains a constant temperature of minus 80 degrees Celsius. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The Cincinnati Museum Center maintains a collection of preserved mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians at the Geier Research Center. Scientists such as curator Heather Farrington are turning to museums to study genetic changes of animal populations over time. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

A spooky-looking fruit bat from the Philippines is preserved on a shelf at the Geier Research Center. The center maintains a large collection of specimens donated by researchers from around the world. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

UC graduate Heather Farrington walks down an aisle in the Zoology Department of the Geier Research Center. Here the museum stores countless wildlife specimens for research. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Heather Farrington kneels next to the Cincinnati Museum Center's great auk, a penguin-like bird that went extinct in the mid-1800s. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

The Cincinnati Museum Center is investigating the origins of its great auk specimen using genetic analysis. Curator Heather Farrington describes how a tissue samples are taken from the base of the foot on these ancient specimens. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

UC graduate Heather Farrington, curator of zoology at the Cincinnati Museum Center, studied the genetics of Galapagos Island finches while she was at UC. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

Discover UC's commitment to Next Lives Here, the strategic direction with designs on leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.

Become a Bearcat

Do you like the idea of conducting your own biology research? Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100. Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

UC celebrates Earth Day 2025 with award-winning publication

April 21, 2025

Earth Day celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. Since its inception, Earth Day has gone global, and with its adoption have come federal intuitions such as the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and policies familiar to most: the Clean Air, Clean Water and Endangered Species acts. This year, UC’s College of Arts and Sciences has reason to celebrate as well. It’s a regional win, capturing the reformation of Fernald, a former nuclear production facility located in northwest Cincinnati. Professor and environmental historian Casey Huegel has received numerous awards for his book, “Cleaning Up the Bomb Factory: Grassroots Activism and Nuclear Waste in the Midwest,” (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books, 2024).

NEXT Innovation Scholar Charlie Harker

April 21, 2025

From strategizing with community leaders on the future of transportation solutions to collaborating with global corporate partners to dive into complex consumer insights, the NEXT Innovation Scholars (NIS) program at the University of Cincinnati empowers a new generation of leaders and problem solvers.

UC study examining overdose hot spots

April 21, 2025

WCPO covered a research collaboration between the University of Cincinnati and the Hamilton County Office of Addiction Response that takes a new approach to help combat the growing overdose crisis in the region.