UC professor examines bias in pigment studies

Molecular anthropologist Heather Norton will speak at the annual American Anthropological Association conference

Recent studies have shown that the genetics underlying skin color are far more complex than we knew.

A University of Cincinnati anthropology professor said these genetic discoveries point to a long-standing Eurocentric bias with implications for forensic science, dermatology and even skin cancer.

Heather Norton, an associate professor of anthropology in UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences, is a molecular anthropologist who has written extensively about the genetics of human pigmentation. Norton will discuss the many genes that contribute to variable skin pigment this week during the American Anthropological Association’s annual conference in Vancouver.

The presentation demonstrates UC's commitment to research as described in its strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

UC anthropology professor Heather Norton says some studies of skin pigmentation reflected a European bias had far-reaching consequences. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

In a paper published last year in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Norton and her co-authors discussed how some studies demonstrated a European sampling bias, providing an incomplete picture of genes responsible for melanin. But new DNA sequencing technology and predictive modeling are revealing just how many genes influence pigmentation and exposing blind spots in studies of melanin.

More than a dozen genes are known to contribute to skin pigmentation. But much of what we know about the underlying genetics of pigmentation comes from studies of European populations.

“That means we have a limited understanding of this complex trait,” Norton said.

“Look at forensic reconstruction. Because forensic panels were developed in this European ancestry context, it’s not necessarily going to be applicable or could wrongly predict appearance,” she said.

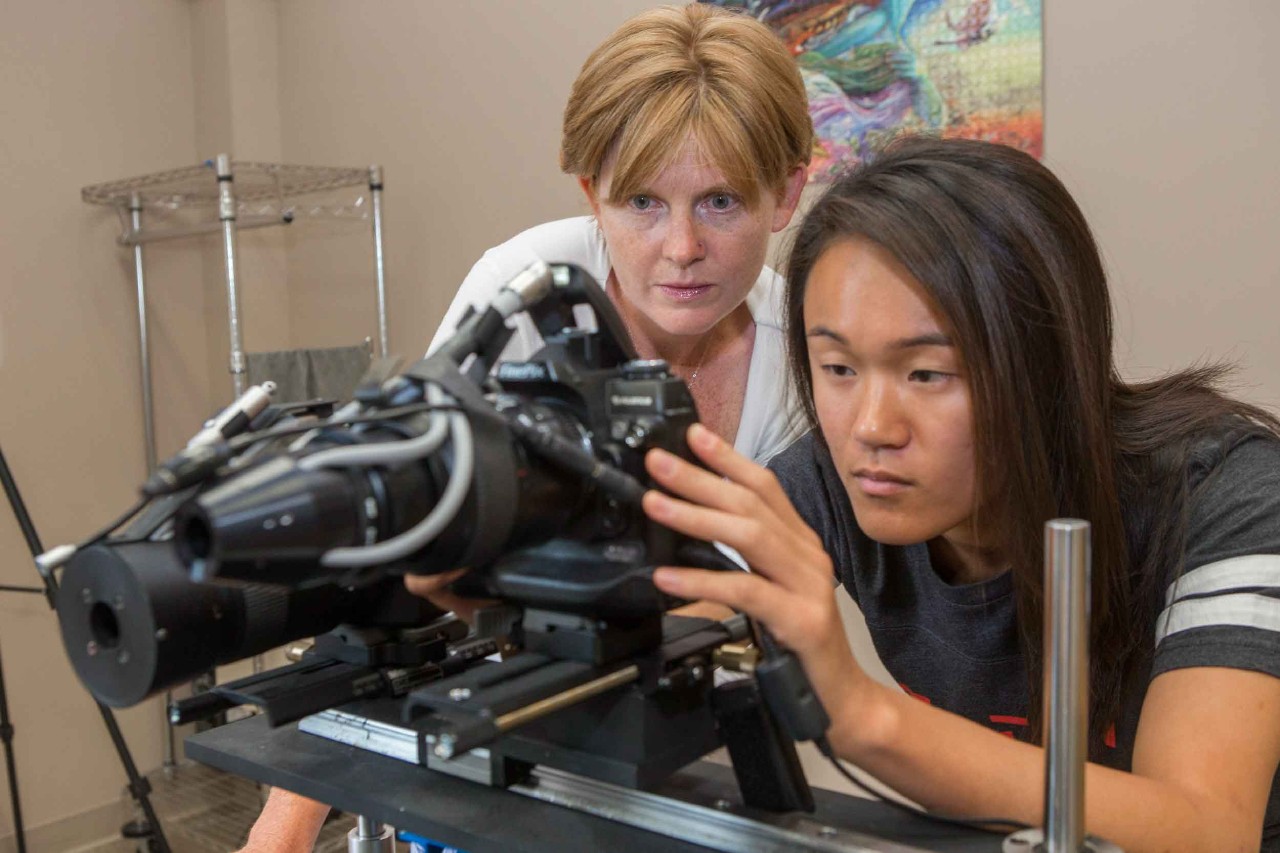

UC anthropologist Heather Norton, left, studies the genetic variability of skin, eye and hair color in her lab. Here she and UC neurobiology student Rebecca Snyder line up a camera. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Melanin is often related to geography and altitude. Generally, people have more melanin in places where the sun’s rays are strongest, along the equator and at higher elevations.

“The pigment in our skin acts as a natural sunscreen, preventing ultraviolet light from penetrating our skin,” she said.

But skin color is extremely variable with the many associated genes passed down from generation to generation. Norton said she wants to understand how different forces shape this genetic variation.

“One of the first things we do is look at how much variation there is across human species,” Norton said.

Dominique Apollon's tweet about an adhesive bandage this year generated a broad conversation about skin pigmentation.

The absence of a diverse genetic map can have broad implications, she said.

“Ultraviolet radiation can cause mutations that can lead to skin cancer. So a lot of times we focus on skin cancer risk in lighter-skin populations,” she said.

Until relatively recently, pigment bias was obvious in consumer goods, too, such as crayons, nylons and makeup.

Just this year, California resident and activist Dominique Apollon tweeted about the surprising emotions he felt wearing his first darker-colored Band-Aid. The tweet generated 546,000 likes and hundreds of concurring comments from people such as Star Wars actor John Boyega, who said makeup artists have to paint his adhesive bandages when he gets cuts on set. Others mentioned the recent availability of ballet slippers and other products matching different skin tones.

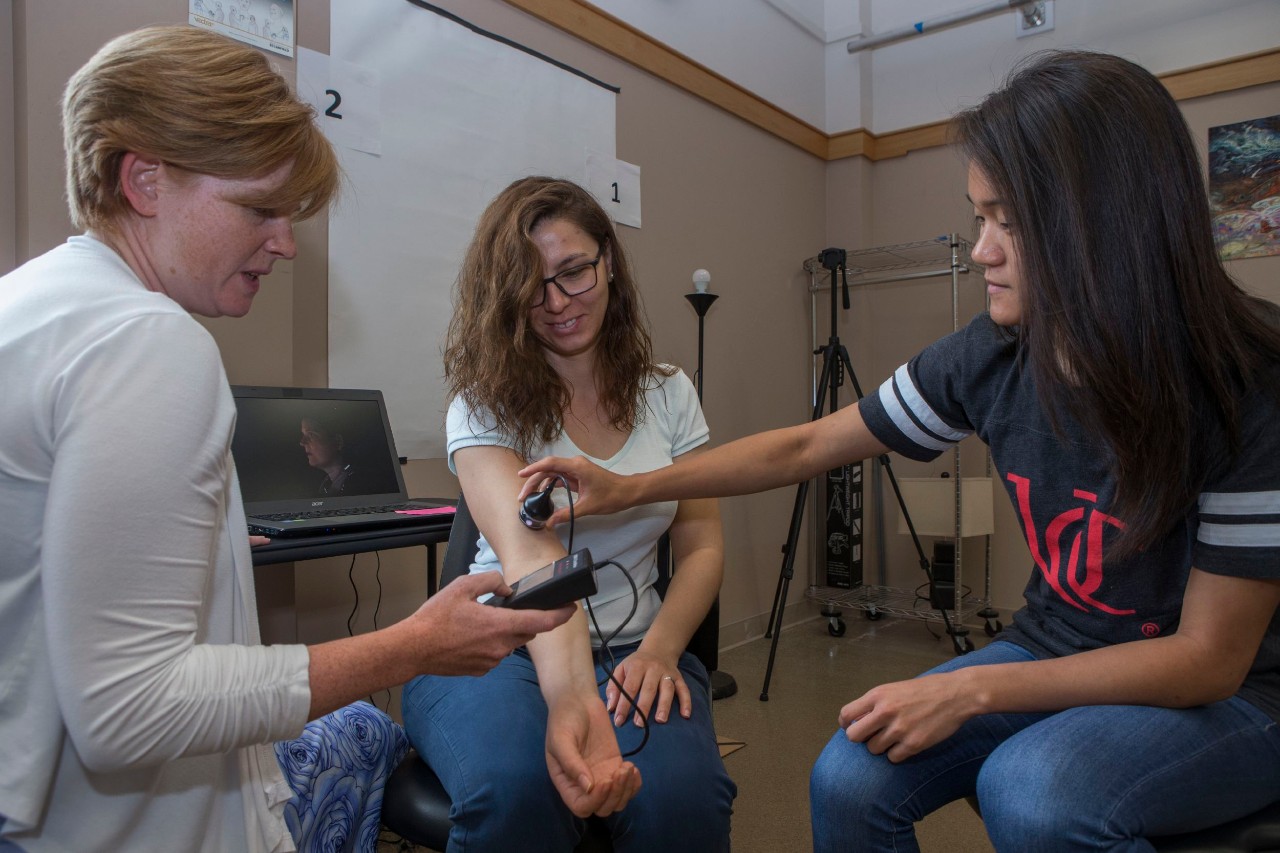

A spectrophotometer measures melanin in the skin. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

“If you start paying attention to the way in the United States and western societies we thought of lighter skin color as the default, it’s not the statistical norm but the cultural norm,” Norton said. “Once you see it, you can’t ‘not’ see it.”

But if melanin is conflated with concepts of race or ethnicity, the risk of skin cancer could be underestimated in some populations, she said.

“There’s a lot of phenotypic variation in those groups. We ignore some of that variation and assume everyone is at the same risk of cancer,” she said.

A 2009 study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology demonstrated that nonwhite patients were more likely than white patients to have undiagnosed psoriasis, a skin condition that increases the risk of developing other medical complications.

And in an increasingly mobile and diverse society, it’s not always possible to make generalizations about the genetics of melanin based on geography.

“We have a good handle on the genes that influence pigmentation in European populations,” Norton said. “More recently, work in other labs examined populations across Latin America and Africa.”

UC associate professor Heather Norton, left, and UC student Rebecca Snyder, right, measure the melanin content of a student's arm. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

A 2019 study in Nature Communications found a broader range of genes that influenced melanin in 6,000 Latin Americans with ancestry from Europe, Africa and North America, she said. The study identified a gene that affects pigmentation in East Asians and Native Americans.

Likewise, a 2017 study of diverse African populations by the University of Pennsylvania identified genetic variants related to skin pigmentation.

“When people think of skin color in Africa, most would think of darker skin, but we show that within Africa there is a huge amount of variation, ranging from skin as light as some Asians to the darkest skin on a global level and everything in between,” Penn professor Sarah Tishkoff told Science Daily.

“Africa is a huge continent with lots of variation. If we don’t look at these other genes, we end up with a flawed view and model,” Norton said.

Featured image at top: UC associate anthropology professor Heather Norton's work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Justice and Procter & Gamble. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC associate professor Heather Norton studies genetic variation in skin, hair and eye color among diverse populations. She serves as co-director of UC's Women in Science and Engineering program. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Become a Bearcat

- Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100.

- Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

It’s a mindset: Meet the visionaries redefining innovation at...

December 20, 2024

Innovation is being redefined by enterprising individuals at UC’s 1819 Innovation Hub. Meet the forward thinkers crafting the future of innovation from the heart of Cincinnati.

UC’s spring Visiting Writers Series promises robust, diverse...

December 20, 2024

Lovers of literature, poetry and the written word can look forward to a rich series of visiting writer presentations, offered through UC’s College of Arts and Sciences department of English, coming this spring.

UC students well represented in this year’s Inno Under 25 class

December 20, 2024

Entrepreneurialism runs through the veins of University of Cincinnati students, as confirmed by the school’s strong representation in this year’s Inno Under 25 class.