UC unlocks genetic lives of bugs

Ambitious international project maps 500 million years of insect evolution

Biologists at the University of Cincinnati are unraveling the genetics behind the flying, swimming, diving, stinging, biting and building diversity of insects.

Joshua Benoit, associate professor of biological sciences in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences, is a co-author of an extensive genetic study on insects, spiders and other arthropods, the largest and most diverse group of animals living on Earth. To date the project’s international researchers have analyzed the genomes of more than 70 species to learn how they evolved and what makes each unique.

The study was published this week in the journal Genome Biology.

“We compared 76 individual genomes from arthropods,” Benoit said. “The goal is to take these and figure out: What makes a fly a fly? What makes a butterfly a butterfly? What is special about insects?”

The international project demonstrates UC's commitment to research as outlined in its strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

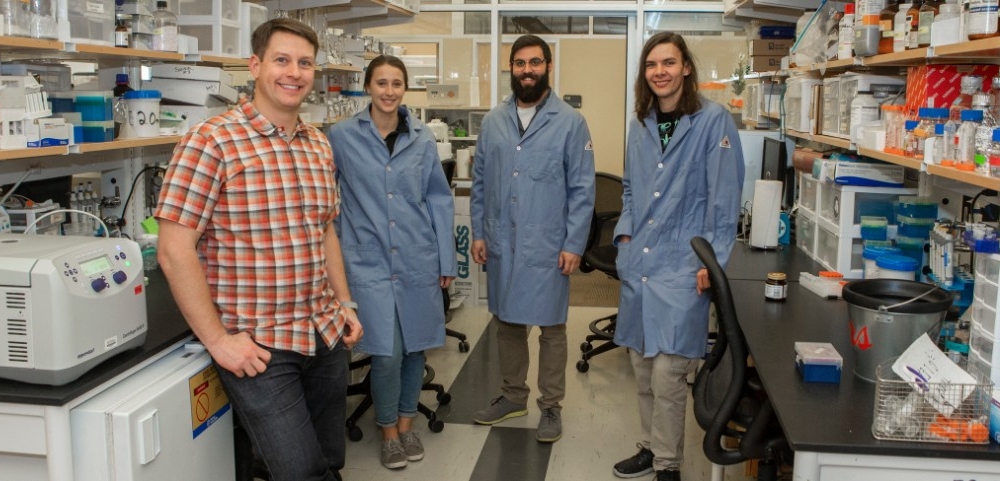

UC biologist Joshua Benoit, left, worked in his lab on an international genome project with his team of graduate students including doctoral students Elise Didion and Chris Holmes and master's student Sam Bailey. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Saving endangered species

The project is called “i5K,” a reference to its goal of mapping 5,000 species of arthropods. It is expected to provide a fundamental understanding of insect genomes for future research that could lead to improvements in pest management and food safety, advances in medicine or conservation of endangered species.

“After almost 10 years, the first phase is wrapping up,” Benoit said.

UC students worked on several of the genomes, including bedbugs, stink bugs and milkweed bugs.

To me, it shows how science needs collaboration.

Elise Didion, UC student on the international i5K project

Sequencing the DNA of an insect is no less complicated than sequencing the human genome. Most humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes. The fruit fly has just four pairs. Others like the female atlas blue butterfly have more than 225.

“In some ways it’s easier today to sequence a human because we’ve sequenced so many human genomes and we can use other genomes as a scaffold. We know what our chromosomes are,” Benoit said. “A lot of these insects were sequenced for the first time. You don’t know where the genes are located and no genome is available.”

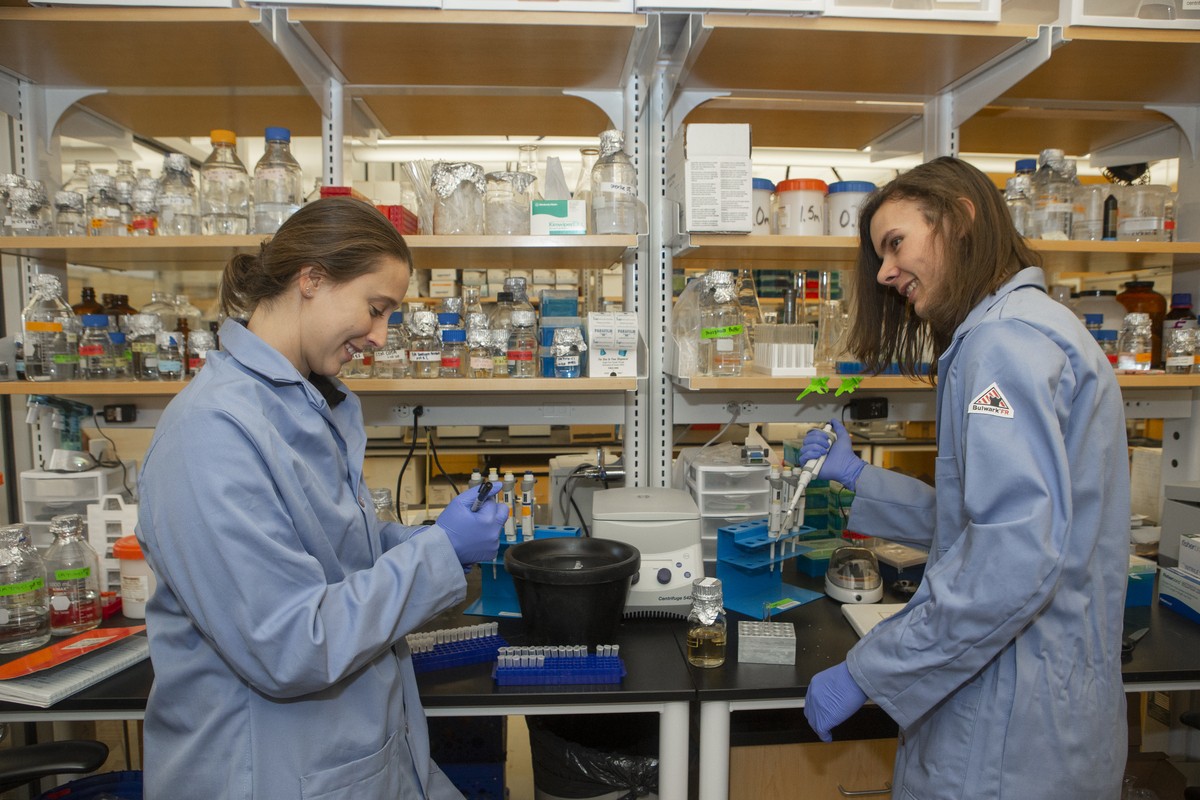

UC students Elise Didion, left, and Sam Bailey worked on the genome project to map arthropods such as bedbugs and milkweed bugs. Here they prepare a genetic sample for a similar project. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Valuable lab experience

Likewise, it’s not easy to get enough DNA from tiny insects to sequence. Initially, the process required interbreeding sibling insects over multiple generations to create genetically similar specimens for sampling.

“Now you can do a genome on a single fly,” Benoit said.

The research is helping scientists understand the genetics that make insects the world’s most diverse creatures, capable of spinning silk, waging chemical warfare or building enormous earthen castles in the sky. And it’s giving biologists an appreciation for how arthropods were able to colonize virtually every habitat on Earth.

The project, led by the Baylor College of Medicine, is helping researchers chart the family trees of arthropods over 500 million years of evolution. The work is building a comprehensive genomic catalog of life on Earth, home to more than 1 million described arthropod species and an estimated seven times that number waiting to be discovered.

“It’s pretty awesome to work on this project,” UC biology student Sam Bailey said.

The project has implications for a range of practical applications such as controlling agricultural pests or vectors for disease, he said.

“You have to find new ways to address these agricultural pests because they can become resistant to pesticides,” Bailey said. “Pesticides can be harmful to more beneficial species like honeybees. So you need to find more effective solutions.”

Joshua Benoit. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC doctoral student Chris Holmes said the project has provided a lot of valuable experience.

“It’s fundamental science to understand insects and their genomes,” Holmes said. “Before this I hadn’t worked in bioinformatics. It was great to get this experience and work with other experts.”

Dozens of biologists from institutions around the world are contributing to the project.

“To me, it shows how science needs collaboration,” UC doctoral student Elise Didion said. “And it’s giving us a great base of data to do future research. People can use these genomes as a springboard for other projects.”

Benoit said UC and other institutions will continue working on other genome projects, publishing as they go.

“One cool thing about a project like this is meeting so many colleagues,” Benoit said. “It opens up a lot of research opportunities you wouldn’t otherwise have.”

Featured image at top: A buckeye moth. Photo/Michael Miller

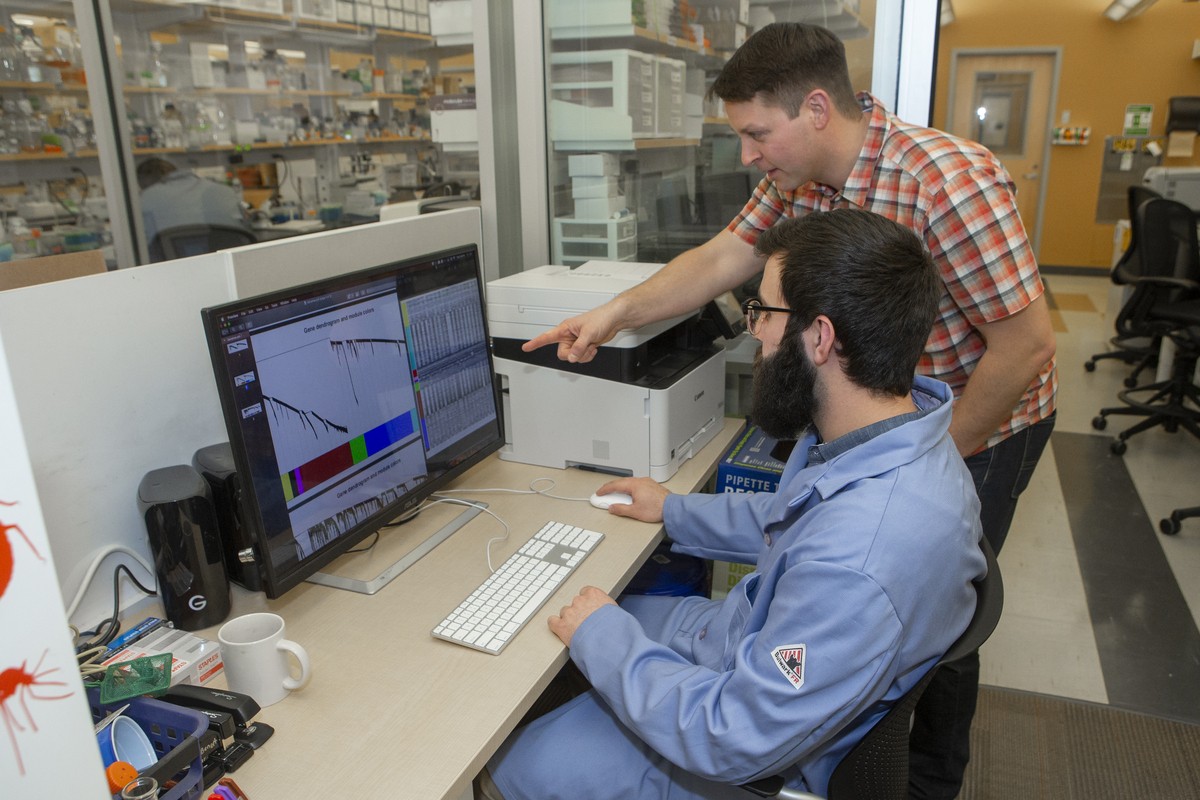

UC associate professor Joshua Benoit, standing, talks to UC doctoral student Chris Holmes about experimental data in an office outside Benoit's biology lab. Benoit's research has taken him around the world, including several expeditions to Antarctica. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Become a Bearcat

- Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100.

- Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

UC students use 1819 Makerspace to build award-winning scoliosis...

December 18, 2024

Three University of Cincinnati students used the 1819 Ground Floor Makerspace to invent and test a groundbreaking treatment for pediatric scoliosis.

How tadpoles make the leap to frogs

December 18, 2024

In his biology lab, UC Professor Daniel Buchholz and his students are using a National Science Foundation grant to study the hormones that trigger metamorphosis in frogs.

UC receives $3.75M in federal funding for K-12 mental health...

December 18, 2024

A three-year, $3.75 million grant from the Department of Education aims to address critical gaps in the mental health and educational landscape by providing tuition stipends for UC graduate students majoring in school and mental health counseling, school psychology and social work.