Why crayfish are successful invaders

UC biologists find that a generalist diet is helping Cincinnati's rusty crayfish take over streams

An invasive species of crayfish that is taking over streams from Wisconsin to Maine might be successful because it’s not a fussy eater, according to biologists with the University of Cincinnati.

In lab “taste tests,” this crayfish native to the Ohio River valley displayed no preference for protein or plants, even after weeks on an exclusive diet of one or the other, according to a new UC study. The crayfish has more cellulose-digesting bacteria when its diet is restricted to plants.

“They tend to be more aggressive than native crayfish,” said Mark Tran, a UC biologist who led the project. “They have relatively large claws compared to their body size. They will either force the other crayfish out or outcompete them for food.”

Tran and his colleagues presented findings from two studies at the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology conference in January.

The continuing project demonstrates UC's commitment to research as outlined in its strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

UC microbiologist Amy Miller holds up an agar plate of bacteria from UC's latest study on rusty crayfish, a species native to Ohio that is invading streams across the north. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

The rusty crayfish looks like a little bronze lobster with its thick body and formidable pincers. It is native to creeks and ponds in Ohio, northern Kentucky and Indiana.

Wildlife managers suspect fishermen who catch rusty crayfish for bait introduced them into streams as far away as Oregon and Canada, where they are outcompeting native crayfish and destroying fish nurseries with their ravenous appetites. According to the Minnesota Sea Grant, the hungry crayfish feed on aquatic vegetation along with invertebrates that baby fish eat.

The irony is that bass fishermen are responsible for releasing them into waters where they end up reducing the native sportfish population.

Mark Tran, UC assistant professor of biology

“The irony is that bass fishermen are responsible for releasing them into waters where they end up reducing the native sportfish population,” said Tran, an assistant professor of biology for UC Blue Ash.

In Canada, Ontario took the extraordinary step of outlawing the transport of any crayfish anywhere in the province to try to stop the rusty crayfish from spreading. Fishermen there have to catch crayfish for bait in the same waters they fish.

“They tend to be opportunistic,” Tran said. “They will actively kill things and eat them. But in the streams we studied, they tend to be more omnivorous. They eat a lot of plant material and supplement it with dead fish or eggs they find.”

UC biology students collected rusty crayfish from a suburban Cincinnati stream for their studies. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

For the project, UC obtained a collection permit from the Great Parks of Hamilton County. Students collected 40 female crayfish from a suburban Cincinnati creek. Half were fed a plant-based diet; the others a meat-based diet.

After a month, the crayfish with the vegetarian diet had more cellulose-digesting bacteria compared to the meat-eating crayfish.

UC assistant professor Mark Tran holds up a rusty crayfish in his biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

“Plants can be hard to digest because of their cell walls,” Tran said. “To get nutrients from the plants, they need bacteria in their gut that can digest that cell wall. Rusty crayfish have a digestive system that is good at breaking down the plant’s cell walls.”

After a month on the strict diet, the crayfish were presented a choice of protein- or plant-based food through plastic tubes in an experimental arena. During a second trial, students offered each crayfish the two food choices in its individual habitat container.

Surprisingly, researchers found variety is not the spice of life for crayfish. The crayfish expressed no statistically significant preference for one food over another in either experiment despite their monthlong restricted diet.

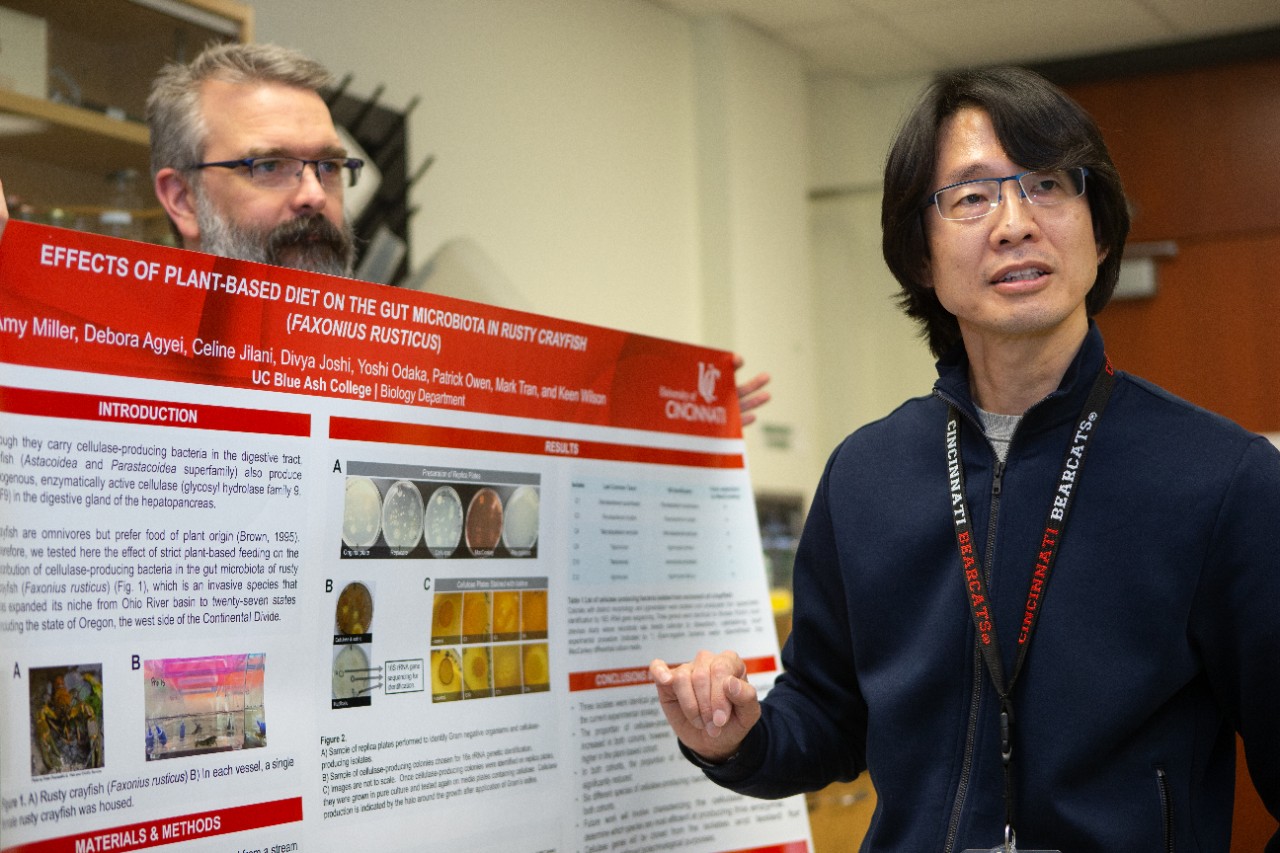

UC biologists Yoshi Odaka, right, and Keen Wilson discuss one of two recent dietary and behavioral studies of rusty crayfish in a UC biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

The findings support what is known about rusty crayfish – they are generalists that will eat almost anything, which helps to explain why they are so successful colonizing new habitats where they are introduced as invasive species.

“Unfortunately, rusty crayfish are well established in Ontario and cannot be eradicated,” said Jolanta Kowalski, a spokeswoman for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. “The introduction of the species occurred in the 1960s and they have become well established.”

This was the third year of UC’s crayfish project, which was conceived to give undergraduate students lab experience, associate professor Keen Wilson said.

“The point is to give students an introduction to a variety of biology specialties,” Wilson said.

“For example, I don’t go outside. I know that about myself, so I stick to lab work,” he said. “But you might not know that about yourself as a freshman. So you go out in the field and collect crayfish and say, ‘I’ll never do that again as long as I live.’ But you might love working in the lab or looking at the microbiology plates.

UC gives undergraduate students the rare opportunity to conduct research, Wilson said.

“When I went to grad school, it was my very first time in a research lab. And that’s not the best way to go in,” he said. “So this is a great opportunity to get your feet wet.”

Increasingly, biology students are interested in doing research projects as undergraduates, assistant professor Yoshi Odaka said.

“Many incoming students are interested in research,” Odaka said. “At open houses, students come up to ask about our undergraduate research programs. We offer great opportunities.”

Featured image at top: Rusty crayfish are thriving in northern streams where they are an invasive species. Photo/Missouri Department of Conservation

UC assistant professor of biology Keen Wilson opens a DNA storage freezer kept at a balmy -80 degrees in a UC biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

UC assistant professor Mark Tran looks through a microscope in his biology lab. He and his colleagues are using rusty crayfish to introduce students to the many specialties of biological sciences. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

UC associate professors Patrick Owen, right, and Keen Wilson discuss their latest collaboration on rusty crayfish in a UC biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

UC associate professor Amy Miller discusses UC's study on bacterial growth in rusty crayfish. UC found that crayfish have more cellulose-digesting bacteria when their diet is restricted to plants, which could explain their success in adapting to new habitats. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

UC biologists Keen Wilson, left, Patrick Owen, Mark Tran, Amy Miller and Yoshi Odaka presented research on rusty crayfish in January at the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology conference in Austin, Texas. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Become a Bearcat

- Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100.

- Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

UC celebrates record spring class of 2025

May 2, 2025

UC recognized a record spring class of 2025 at commencement at Fifth Third Arena.

‘Doing Good Together’ course gains recognition

May 1, 2025

New honors course, titled “Doing Good Together,” teaches students about philanthropy with a class project that distributes real funds to UC-affiliated nonprofits. Course sparked UC’s membership in national consortium, Philanthropy Lab.

DAAPworks reveals 2025 Innovation Awards – discover the winning...

May 1, 2025

Visionary projects stole the show during DAAPworks 2025, from wayfinding technology for backcountry skiers to easy-to-use CPR training kits for children.