UC’s chemistry museum dates back to days of alchemy

The UC College of Arts and Sciences boasts one of the nation's few museums dedicated to chemistry

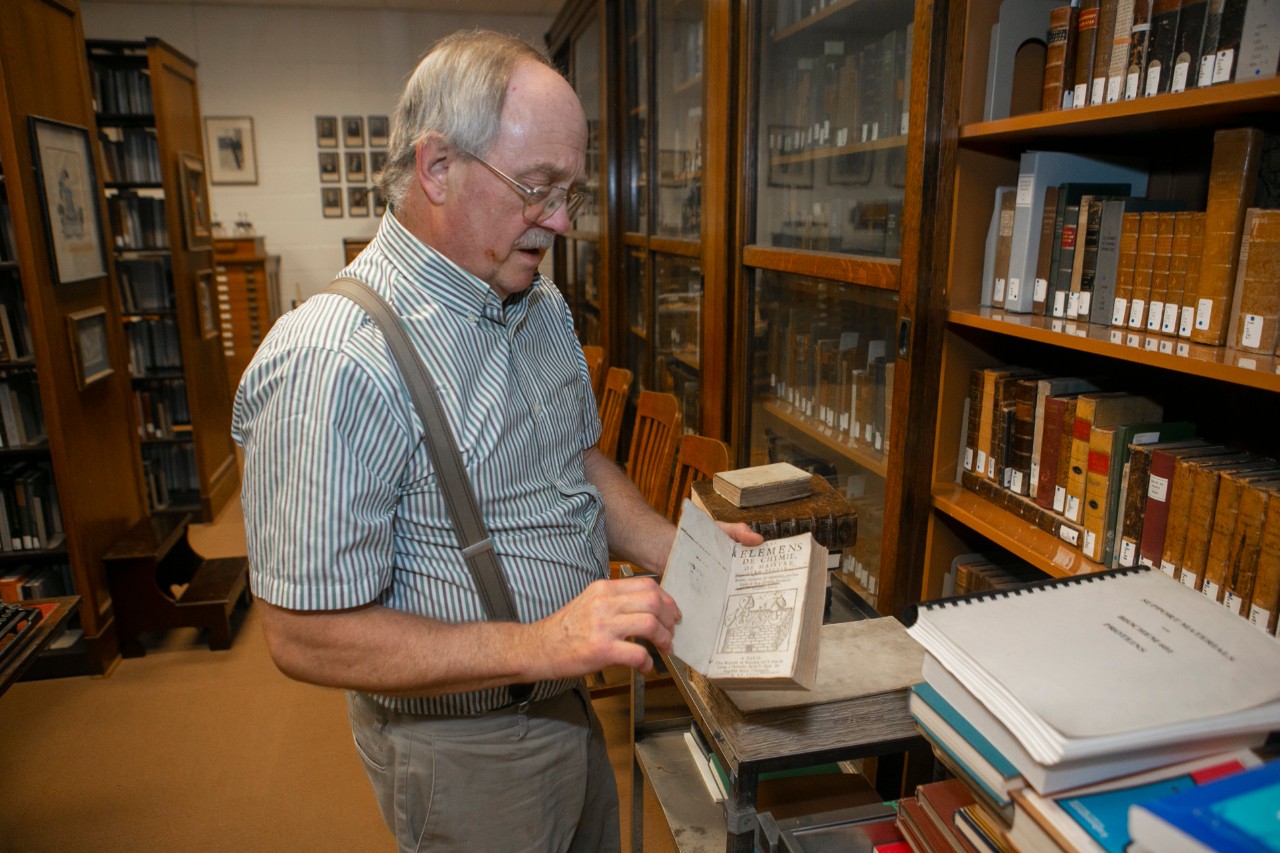

Rudy Thomas plucked a leatherbound book off a shelf and opened its crinkled cover.

“Elemens de Chymie,” French for “Elements of Chemistry,” was published in 1624 — just eight years after England mourned the death of William Shakespeare. Today, the book is among hundreds of rarities in the University of Cincinnati’s chemistry library and museum known as the Oesper Collection.

“Even by our standards, this book is old — very old,” said Thomas, a research associate in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Everything is relative. I come from a geochemistry background as an inorganic chemist. Some of the minerals I study date back 600 million years.”

Besides rare books, the collection on the fifth floor of Rieveschl Hall houses laboratory equipment dating back two centuries. Its odd instruments, custom glassware and bottles of inert compounds would look at home in a Harry Potter movie.

The chemistry museum recognizes the foundations of science even as UC researchers lead advances in the field as part of UC's strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

UC's chemistry museum contains a collection of rare chemistry books, signed portraits of scientists and historical laboratory equipment. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Historical context

UC is one of the few universities in the United States with its own dedicated museum to chemistry. But embracing the past is important to understanding the foundations of research, department head Thomas Beck said.

“I think it gives students context of where things came from. It also teaches you modern technology is important but not essential to good science. Great experiments were done 100 years ago,” he said. “Just to get that context of historical development is really important.”

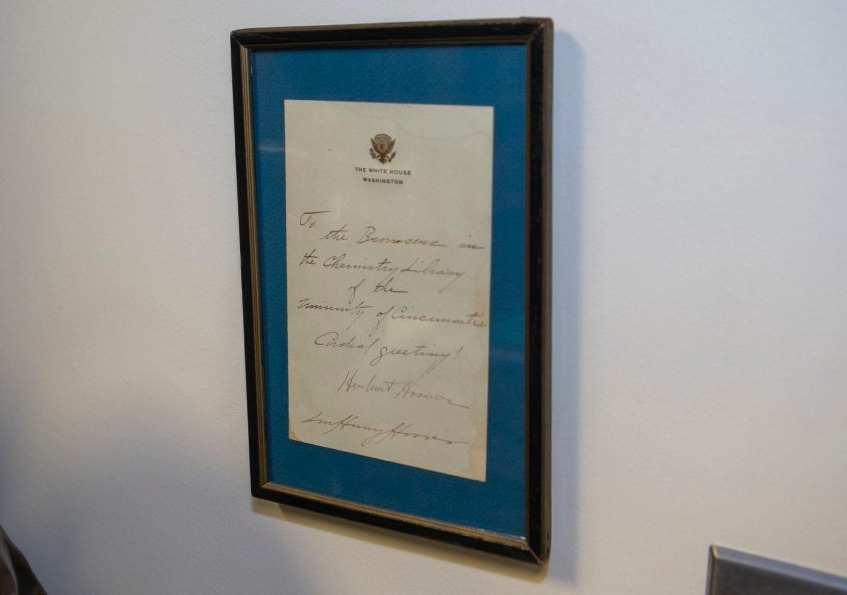

Near the entrance to the museum library, a framed letter on White House stationery reads, “To the Browsers in the Chemistry Library of the University of Cincinnati, cordial greetings!” It was signed by President Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry Hoover, both of whom worked as geologists.

I have always been puzzled that anyone could devote their career to a subject and not have any curiosity about where all of this stuff came from.

William Jensen, Longtime curator of UC's Oesper Collection

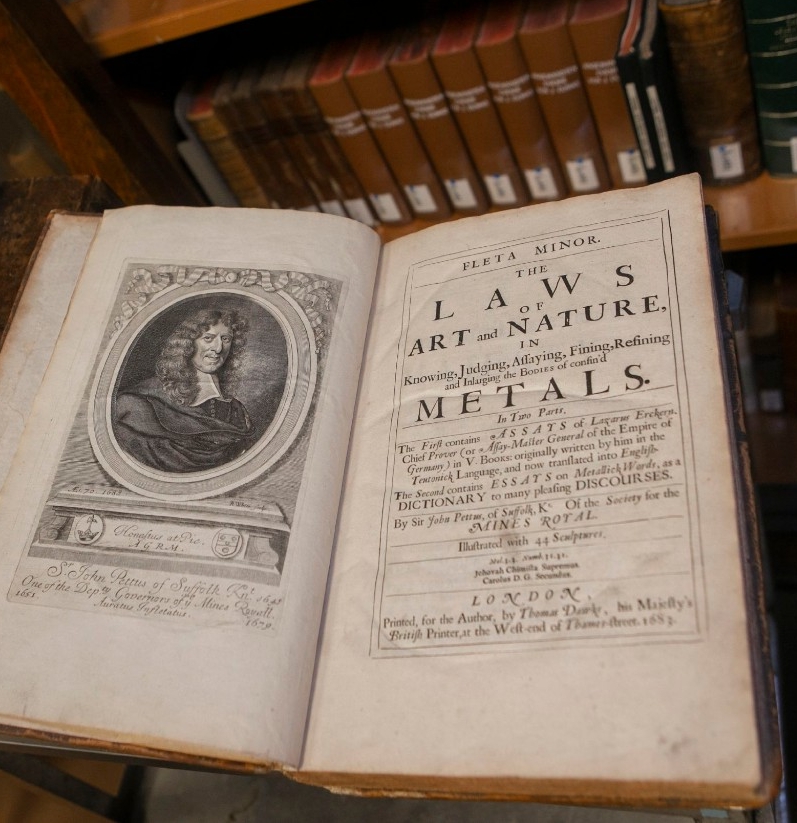

The couple in 1912 worked together to translate a Latin chemistry text from 1556 called “De Re Metallica” (“On the Nature of Metals”) by German metallurgist Georgius Agricola. When Hoover was campaigning for federal office in 1928, the UC museum’s curator at the time and now its namesake, Ralph Oesper, scrambled to obtain copies of Hoover’s translation, bound in white calfskin.

Today, it’s Thomas’ favorite book in the entire collection.

“It’s a goodie. I’m an inorganic chemist so I deal with the periodic table. I have a huge interest in geochemistry,” he said.

UC professor emeritus William Jensen, left, talks about the Oesper Collection with UC chemistry department head Thomas Beck and UC research associate Rudy Thomas in the chemistry museum. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Hunting for rarities

UC professor emeritus William Jensen for years has worked as the museum’s curator. Like Oesper before him, Jensen has been on a lifelong quest for rare chemistry texts and unusual equipment.

“I would travel from Georgia to Minnesota to give talks on the history of chemistry and chemistry equipment,” Jensen said. “Invariably, there were always people willing to take me down into some basement or show me old storerooms.They were happy to see this old equipment find a home rather than go in the trash bin.”

UC chemistry professor emeritus William Jensen curated the Oesper Collection after Ralph Oesper's retirement. He was able to save historical laboratory equipment that is now on display at UC. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Serendipity was not always in his favor.

“Sometimes they would tell me of things they had just thrown out,” Jensen said, wincing. “I was too late.”

Many of the books and journals are in foreign languages: Chinese, Japanese, Italian. As with any science, chemistry transcends language, Jensen said.

“We buy by subject matter. If it’s an important monograph, we bought it irrespective of language,” Jensen said.

Some of the Oesper Collection texts harken back to the medieval forerunner of chemistry called alchemy, which arguably was more art than science. Alchemy is associated with the quixotic effort to transmute lead into gold. But some esteemed scientists such as Isaac Newton were alchemists.

“I consider alchemy to be pseudoscience like astrology. But there are historians who argue it was a science,” Jensen said. “It made heavy use of metaphor. ‘The green lion eats the sun.’ This has been translated as nitric acid dissolving gold. The trouble with metaphors is one person’s guess is as good as another’s.”

UC research associate Rudy Thomas opens a copy of the chemistry museum's "Elemens de Chymie," a French chemistry book published in 1624. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Comprehensive collection

Like many chemists, Jensen loves books. He has two dozen just on chemical thermodynamics.

“Why would anyone want 24 books on the same topic?” Jensen asked. “Each book approaches the topic differently. And when you look at the different ways people have tried to grasp the subject, it enhances your own understanding.”

Before running for president, geologist Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry, translated a historic book on metals. UC's former chemistry museum curator, Ralph Oesper, purchased a copy during Hoover's successful presidential campaign. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services.

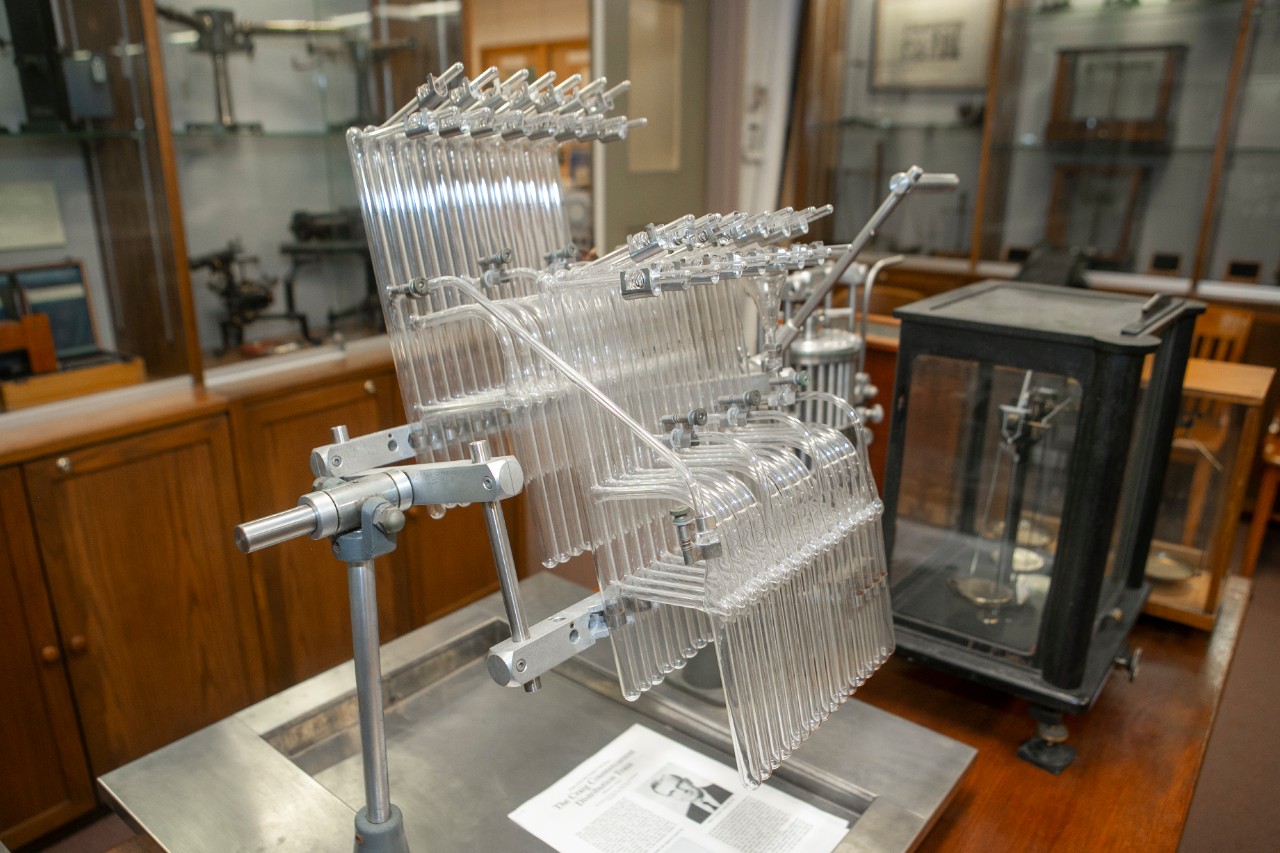

The museum features a laboratory re-created from 1900 complete with a custom-made wood cabinet and vapor hood. On a table is a bundle of glassware that resembles a pipe organ that chemists used to separate compounds from a solution. The shelves hold glass-stoppered bottles full of inert compounds with weathered, yellowed labels.

And the museum has a collection of signed photographic portraits of famous scientists such as Marie Curie and Niels Bohr.

The Oesper Collection is presided over by a white plaster bust of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, known as the father of modern chemistry. The tribute is somewhat ironic, said Jensen, who arranged for its purchase.

“Lavoisier got in trouble during the French Revolution and was beheaded by guillotine,” Jensen said.

A signed portrait of famed scientist Marie Curie hangs in UC's chemistry museum. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC’s collection includes more than 28,000 chemistry journals and 10,000 monographs dating back to the 16th century. But its wood cabinets, glass displays and artwork depicting early medieval laboratories evoke a sense of history.

Jensen said he has always had a keen appreciation for the groundbreaking work of early chemists and the innovative tools they designed for their experiments.

“I have always been puzzled that anyone could devote their career to a subject and not have any curiosity about where all of this stuff came from,” he said.

“I’ve always viewed my interest in the history of chemistry as part of my chemical education. It gave me a much more secure understanding of chemistry and its theories than I would have otherwise.”

Featured image at top: UC professor emeritus William Jensen poses in front of a display case in UC's chemistry museum, which contains rare books, portraits of scientists and historical laboratory equipment. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

A handwritten letter from President Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry, greets visitors to the library of UC's chemistry museum. The couple were geologists before they went into politics. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC chemistry department head Thomas Beck poses in the library of UC's chemistry museum. The library contains hundreds of historical books on chemistry from around the world. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC professor emeritus William Jensen stands in front of a custom chemistry cabinet that had a built-in fume hood in a re-creation of a 19th century lab in UC's chemistry museum. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC's chemistry museum features custom glassware equipment called a Craig countercurrent distribution train that chemists used to separate solutions. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC's chemistry museum features a bust of Antoine Lavoisier, known as the father of modern chemistry. The plaster tribute is somewhat ironic because Lavoisier was executed by guillotine during the French Revolution. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC's chemistry museum features a re-created 19th century chemistry lab. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Become a Bearcat

- Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100.

- Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

It’s a mindset: Meet the visionaries redefining innovation at...

December 20, 2024

Innovation is being redefined by enterprising individuals at UC’s 1819 Innovation Hub. Meet the forward thinkers crafting the future of innovation from the heart of Cincinnati.

UC students well represented in this year’s Inno Under 25 class

December 20, 2024

Entrepreneurialism runs through the veins of University of Cincinnati students, as confirmed by the school’s strong representation in this year’s Inno Under 25 class.

UC professor Ephraim Gutmark elected to National Academy of...

December 20, 2024

Ephraim Gutmark, distinguished professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati, was elected to the 2024 class of the prestigious National Academy of Inventors.