NASA names UC grad Sagan fellow

Astronomer Kevin Wagner is searching for new planets beyond our solar system

NASA awarded a prestigious physics fellowship to a University of Cincinnati graduate who is hunting for planets new to science.

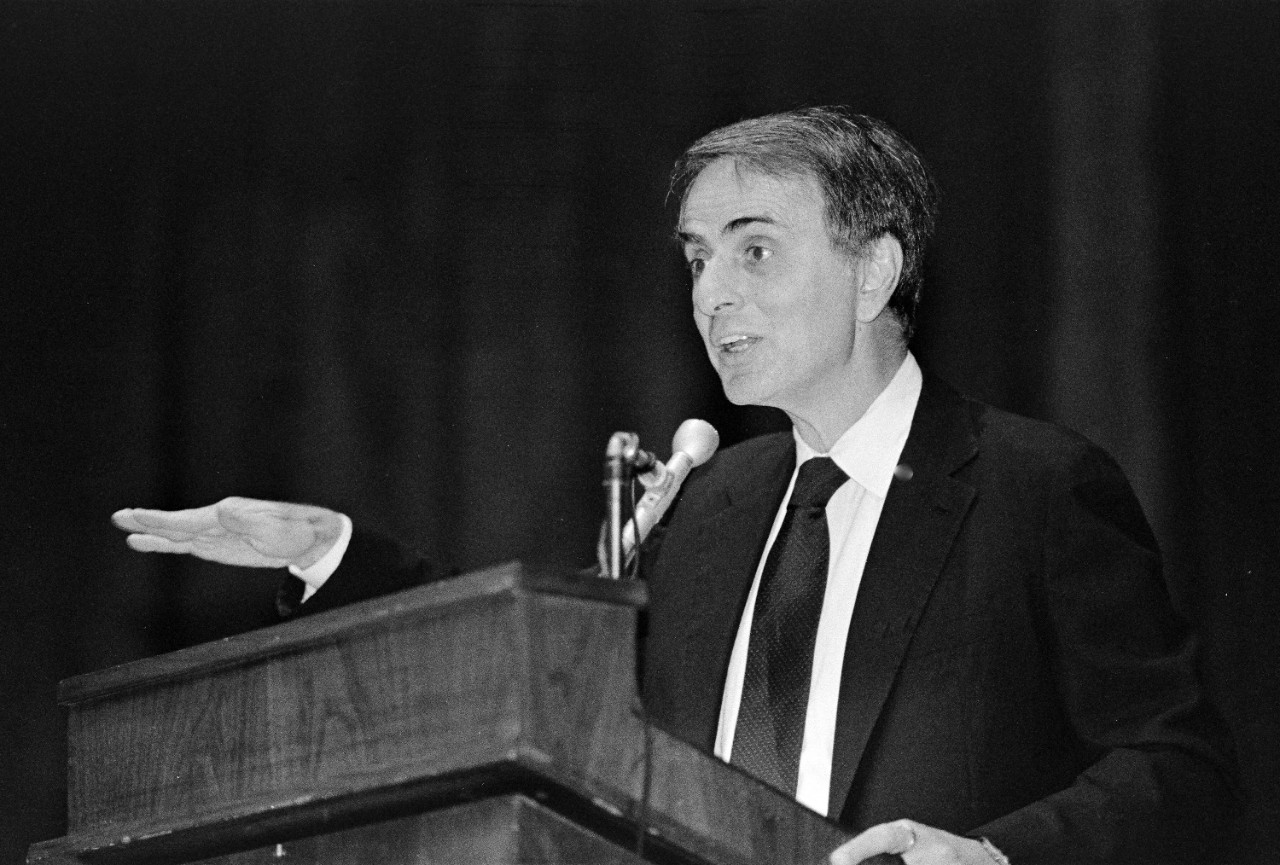

UC College of Arts and Sciences graduate Kevin Wagner was named a Sagan Fellow as part of NASA’s Hubble Fellowship Program. The late Carl Sagan was a famed astronomer and astrophysicist known for his popular PBS series “Cosmos.”

Wagner is working on his doctoral degree at the University of Arizona, home to the Steward Observatory. He is studying how planets form. He also has been looking for solar systems with potentially habitable planets like ours.

“He’s one of the best students I ever had,” UC physics professor Michael Sitko said.

“He is definitely an overachiever. He was lead author of a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal, one of the top astrophysics journals, before he even graduated from UC,” Sitko said.

“He also received a National Science Foundation research fellowship even before he left for Arizona,” Sitko said. “I knew he was going to be doing great things.”

The W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii uses laser-guided optics. Photo/Kevin Wagner

Student-led research

In 2018, Wagner and a team of international researchers imaged a newly forming planet with the Magellan Clay telescope in Chile.

Wagner, a native of northern Kentucky, said he will use his fellowship to continue his quest for new planets outside our solar system. Improvements in imaging technology allow astronomers to look for smaller and smaller objects in the vastness of space.

The late Carl Sagan. Photo/Kenneth C. Zirkel/Wikimedia Commons

Until now the planets that researchers have imaged are colossal — far bigger than even the biggest planet in our solar system, Jupiter. For his fellowship, Wagner will use the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona to identify the infrared signature of much smaller planets.

“The specific project is to upgrade the imaging capabilities of the Large Binocular Telescope. It’s the largest optical imaging telescope in existence,” Wagner said.

It uses twin 27-foot-wide mirrors that provide formidable tools to peer into the universe. It has a suite of cameras and other sensitive equipment to record the telescope’s observations.

“With this program I want to push our limits to the size of Neptune,” he said.

Neptune, too, is huge — 17 times more massive than Earth. But it’s 19 times smaller than Jupiter. Being able to find planets this size opens up a huge window of opportunity for discovery, Wagner said.

It’s always in the back of our minds. Is there someone else out there? What is life on another planet like? Now we can answer those questions.

Michael Sitko, UC physics professor

Equally important, Wagner will be looking for these planets in close proximity to their stars to potentially harbor life. Physicists call this the “habitable zone.” And it’s comparatively tiny.

Wagner said this is the combination of distance from the sun and atmospheric conditions to support liquid water on a solid planet.

Wagner is not alone in this quest.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in 2018 published the Exoplanet Science Strategy, a blueprint for harnessing the world’s astronomical resources to search for potentially habitable planets like ours.

“For generations, humans have looked up at the stars and wondered whether we are alone,” the academy’s lead author, Aaron Gronstal, wrote.

“Wonder at this very question unites us. The Exoplanet Science Strategy describes how researchers can aim to address this question in a generation. It is unknown whether this generation will be the first to learn that life is common throughout the galaxy or the first to discern hints of a cosmic lonesomeness. What we do know is that we can be the first with the technological and scientific ability to answer the question, if we so choose.”

UC’s Sitko has worked with his former student on several research projects, including ongoing studies of how planets form. Sitko said one prevailing theory is that newly formed stars spin. Cosmic dust surrounding them gathers at the sun’s equator in a planet-forming disk that astronomers can detect from Earth.

Knowing how to identify these disks can help astronomers predict where they might find exoplanets, Sitko said.

“You can use the structures of these disks as a diagnostic tool: ‘There should be a planet right about here,’” he said.

UC physics professor Michael Sitko and UC graduate Kevin Wagner are looking for new planets beyond our solar system. Photo/Kevin Wagner

Life-supporting planets

Sitko and Wagner collaborated on a 2018 article published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics that used spectroscopy to study a triple-star system. And last year they worked together with a research team that used the Subaru Observatory in Hawaii to examine a protoplanetary disk that could harbor a hidden planet or planets for a study in the Astrophysical Journal.

“Every time there is new technology, we can do things we couldn’t do before. That will always guarantee new discoveries,” Sitko said. “Once we invented radio telescopes, we could identify cosmic background radiation. With optical telescopes we could find out the universe was expanding.”

And the unspoken question connecting virtually all of the research: Are we alone in the universe?

“It’s always in the back of our minds. Is there someone else out there? What is life on another planet like?” Sitko said. “Now we can answer those questions.”

Wagner said he has been spending the recent COVID-19 quarantine working on his dissertation. A former member of UC’s Mountaineering Club, Wagner is an avid rock climber. He scaled the 3,600-foot-tall granite peak El Capitan in Yosemite National Park just days after world-famous climber Alex Honnold did so without benefit of safety ropes as documented in the independent documentary, “Free Solo.”

“We happened to be on El Cap a week after he did that and followed the same route he took. We could see some of his chalk tick marks on finger holds he used,” Wagner said.

“It took us a week to summit El Capitan — the same time it takes to image a Neptune-sized exoplanet!” Wagner said.

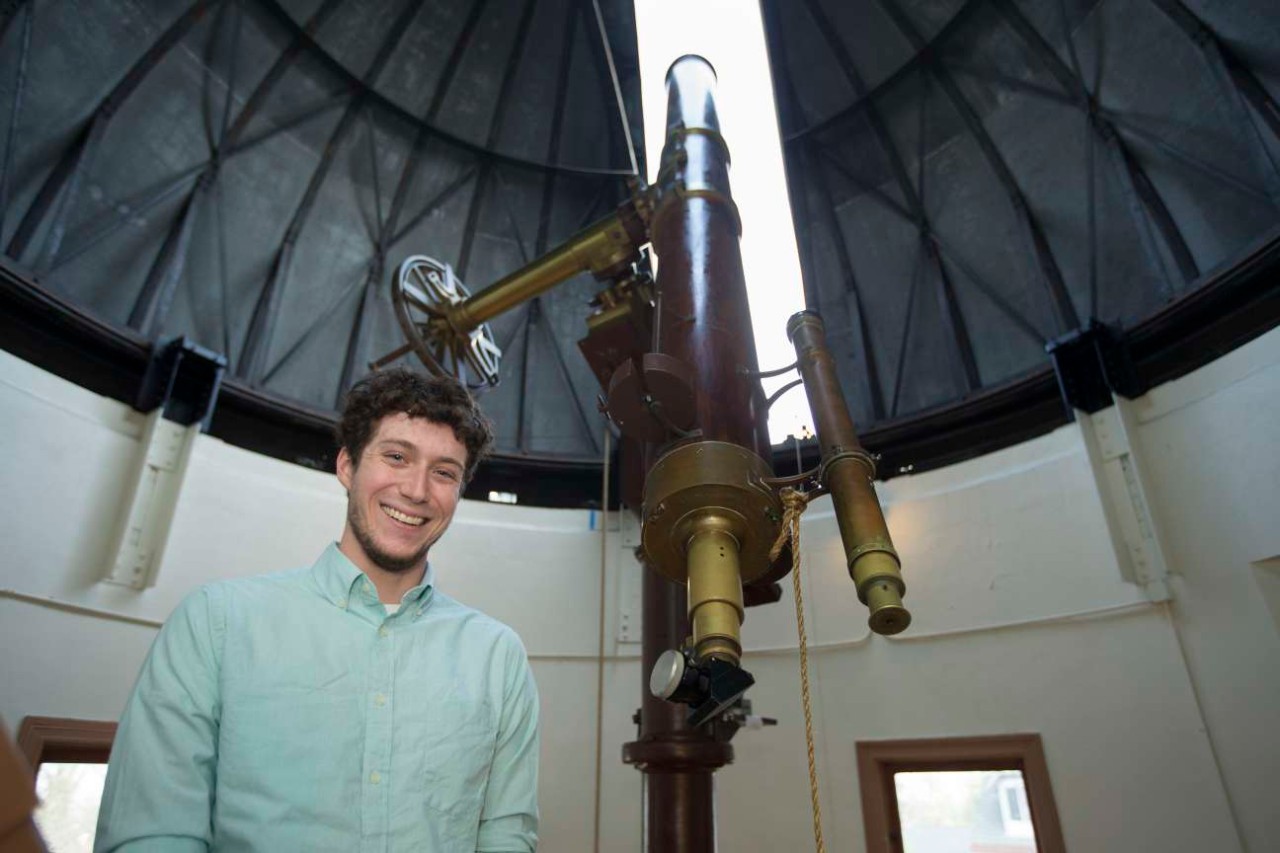

UC graduate Kevin Wagner poses in front of the historic telescope at the Cincinnati Observatory. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Creative + Brand

University of Cincinnati graduate Kevin Wagner poses at the Cincinnati Observatory where he volunteered as a student. He is pursuing his doctoral degree at the University of Arizona. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Creative + Brand

Impact Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Take a UC virtual visit and begin picturing yourself at an institution that inspires incredible stories.

Related Stories

UC celebrates record spring class of 2025

May 2, 2025

UC recognized a record spring class of 2025 at commencement at Fifth Third Arena.

UC students recognized for achievement in real-world learning

May 1, 2025

Three undergraduate University of Cincinnati Arts and Sciences students are honored for outstanding achievement in cooperative education at the close of the 2024-2025 school year.

‘Doing Good Together’ course gains recognition

May 1, 2025

New honors course, titled “Doing Good Together,” teaches students about philanthropy with a class project that distributes real funds to UC-affiliated nonprofits. Course sparked UC’s membership in national consortium, Philanthropy Lab.