Ohio’s COVID-19 experience offers lessons

UC found airports and highways helped coronavirus spread across Ohio's high-density populations

COVID-19 has spread fastest across Ohio in the counties with the densest population and with commercial airports, according to a study by the University of Cincinnati.

The study in the journal Health & Place was the first published by UC’s Geospatial Health Advising Group, which has been helping Ohio track the global pandemic across the state and make future projections.

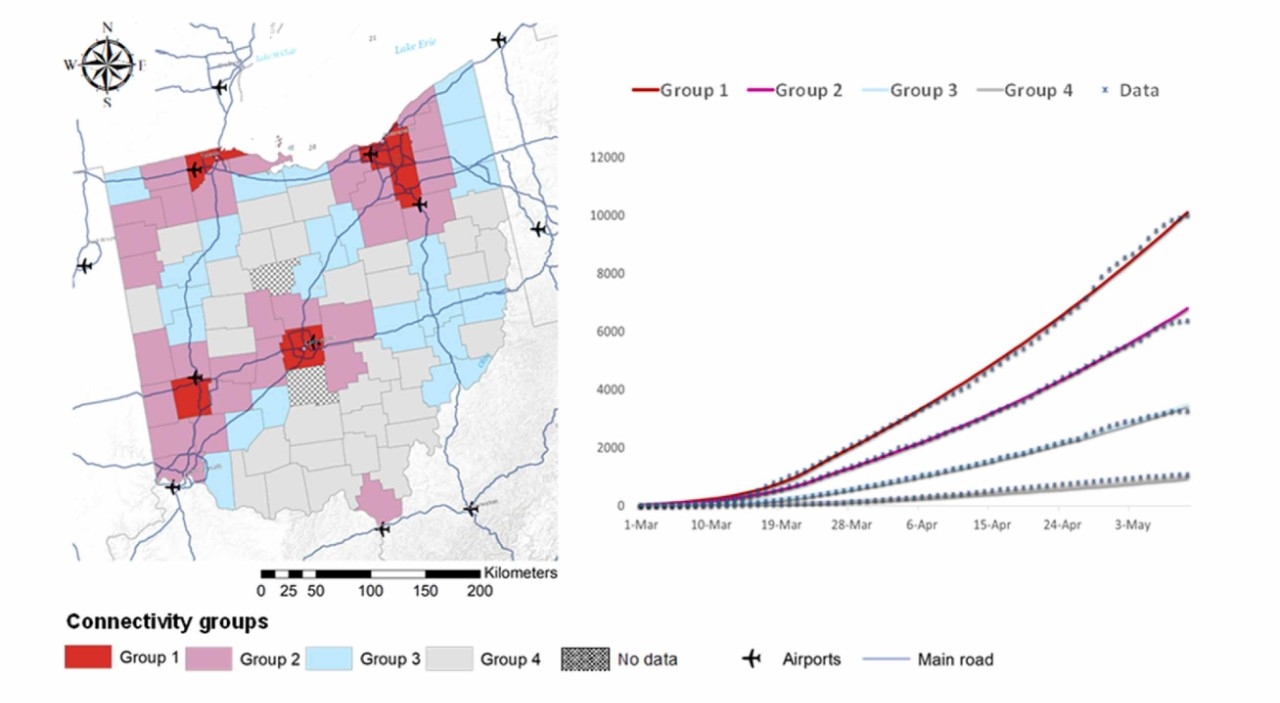

The study describes the uneven impact COVID-19 has on populations based on their density and how connected or removed they are to larger metropolitan areas. They found that per capita infection rates are far higher in high-density areas compared to rural ones.

“The most important part was to show the spatial differences between urban and rural areas. Urban or highly connected areas had a faster spread of the disease,” said Diego Cuadros, lead author and an assistant professor of geography in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences.

The study demonstrates UC's commitment to research as described in its strategic plan called Next Lives Here.

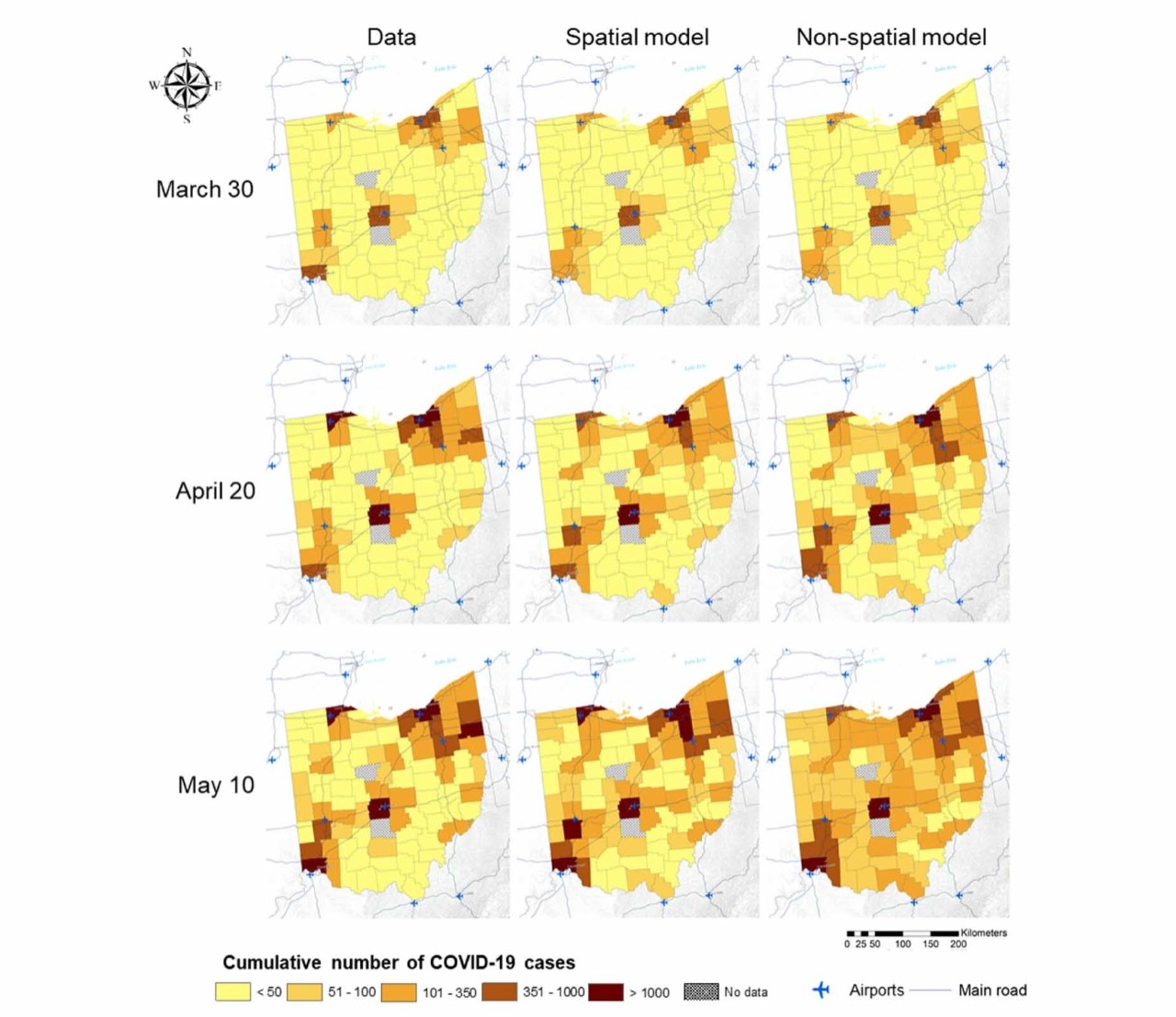

UC found a correlation between the spread of coronavirus and airports and highways in Ohio. Graphic/UC

UC’s group submitted two public health policy briefs containing its projections to Ohio’s Department of Health in April and May based on its geospatial analysis. The group includes members from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, UC’s College of Pharmacy and UC’s departments of math and geography.

UC’s projections were spot on. In April, UC researchers projected 21,430 new cases by May 10. The confirmed number: 20,763. UC researchers projected 4,318 related hospitalizations. The actual number: 4,054. And they estimated 1,529 coronavirus-related deaths where the actual number was slightly lower at 1,421.

UC in April also projected the consequences for different scenarios to reopen Ohio after the weeks-long quarantine. Had Ohio lifted all social-distancing restrictions, UC predicted the state would see a surge in cases that would require another shutdown after just six weeks.

Meanwhile, the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy also examined the UC group's work in an article published in August. UC researchers found that Ohio's interventions such as closures and social-distancing rules saved 700 lives and cut hospitalizations by 10,000 patients through mid-April.

UC College of Pharmacy Dean Neil MacKinnon, a study co-author, told the journal that lifting social-distancing restrictions too quickly can have dire consequences.

"Hopefully, our brief is a powerful reminder that if you relax restrictions too fast, there is a very high likelihood that people will die unnecessarily," he told the journal. "If states let up, we may be back where we were before, where we are worried about capacity issues."

This tracks with what we saw. We weren’t hit as hard early on in the pandemic. It’s interesting that the UC maps bore that out.

Richard Shonk, Health Collaborative

Cuadros runs UC’s Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab. He has studied diseases such as malaria and HIV in countries around the world.

The way COVID-19 has spread fastest across Ohio’s population centers is consistent with the experience of other countries, Cuadros added.

“We are seeing the same patterns in many other countries,” he said. “Places with international airports are the first to see infections. The infection spreads very fast in those provinces and places where there is a lot of connectivity from highways and circulation of people.”

UC's analysis found that coronavirus spread quickly and broadly in counties that included or were adjacent to major commercial airports. The rate of cases was highest in these counties. Graphic/UC

Researchers examined the spread of the disease in Ohio from March 1 to April 25 and validation data from April 26 to May 10 although it appears the first COVID-19 infections in Ohio were in January, Cuadros said.

UC found substantial variation in the spread and intensity of infection among risk groups in different places.

The study found that nearly half of confirmed cases in Ohio were concentrated in just five counties with similar characteristics. They all had dense populations and are home to high-traffic airports that likely facilitated the spread of coronavirus from other states or Ohio cities.

“As projection models go, it lined up well with our experience,” said Richard Shonk, MD, chief medical officer for the Health Collaborative, a nonprofit group based in Cincinnati dedicated to improving medical care and health outcomes and coordinating a regional response to disasters such as the current pandemic.

“This tracks with what we saw. We weren’t hit as hard early on in the pandemic. It’s interesting that the UC maps bore that out,” he said.

Shonk was not part of the UC study but has closely followed COVID-19 cases across the state, particularly in southwest Ohio.

“Most of the folks in the business of doing projection models tell you it’s never exact,” he said. “But anecdotally, the projections mirrored our experience here. Greater Cincinnati was not as much of a hot spot compared to Franklin and Cuyahoga counties.”

Shonk said he is curious why Hamilton County in the early stages of the pandemic didn’t see the same high rates of infection as other high-population places in Ohio with major air hubs like Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport.

“We seemed to be relatively spared,” he said. “We’d like to think it’s because we were more proactive in addressing the threat of infection in the nursing home population, identified as the most vulnerable to this disease.”

Now researchers are trying to understand why coronavirus is surging in some rural parts of the United States, Cuadros said.

Understanding local COVID-19 transmission is crucial in designing effective control programs, the study said.

Featured image at top: An airport terminal before the pandemic. Photo/Tomek Baginski/Unsplash

UC assistant professor Diego Cuadros has studied diseases such as malaria and HIV around the world. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

UC experts tackle coronavirus

UC's Geospatial Health Advising Group has been studying the spread of coronavirus across Ohio. Photo/Volodymyr Hryshchenko/Unsplash

Researchers in colleges across UC have been studying aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- UC launches Phase 3 clinical trial for COVID-19 vaccine

- UC COVID-19 research examines the safety and efficacy of immune-regulating drug

- Silk offers homemade solution for COVID-19 prevention

- UC study uncovers clues to COVID-19 in the brain

- Residents in some Ohio counties face greater risk from COVID-19

- UC provides road map to reopen Ohio

Impact Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Stay up on all UC's COVID-19 stories, read more #UCtheGood content, or take a UC virtual visit and begin picturing yourself at an institution that inspires incredible stories.

Related Stories

UC students recognized for achievement in real-world learning

May 1, 2025

Three undergraduate University of Cincinnati Arts and Sciences students are honored for outstanding achievement in cooperative education at the close of the 2024-2025 school year.

DAAPworks reveals 2025 Innovation Awards – discover the winning...

May 1, 2025

Visionary projects stole the show during DAAPworks 2025, from wayfinding technology for backcountry skiers to easy-to-use CPR training kits for children.

Everything you need to know about scents and your hair

May 1, 2025

The University of Cincinnati's Kelly Dobos was featured in an NBC News article discussing the science behind hair fragrances and shampoos.