When art reflects life

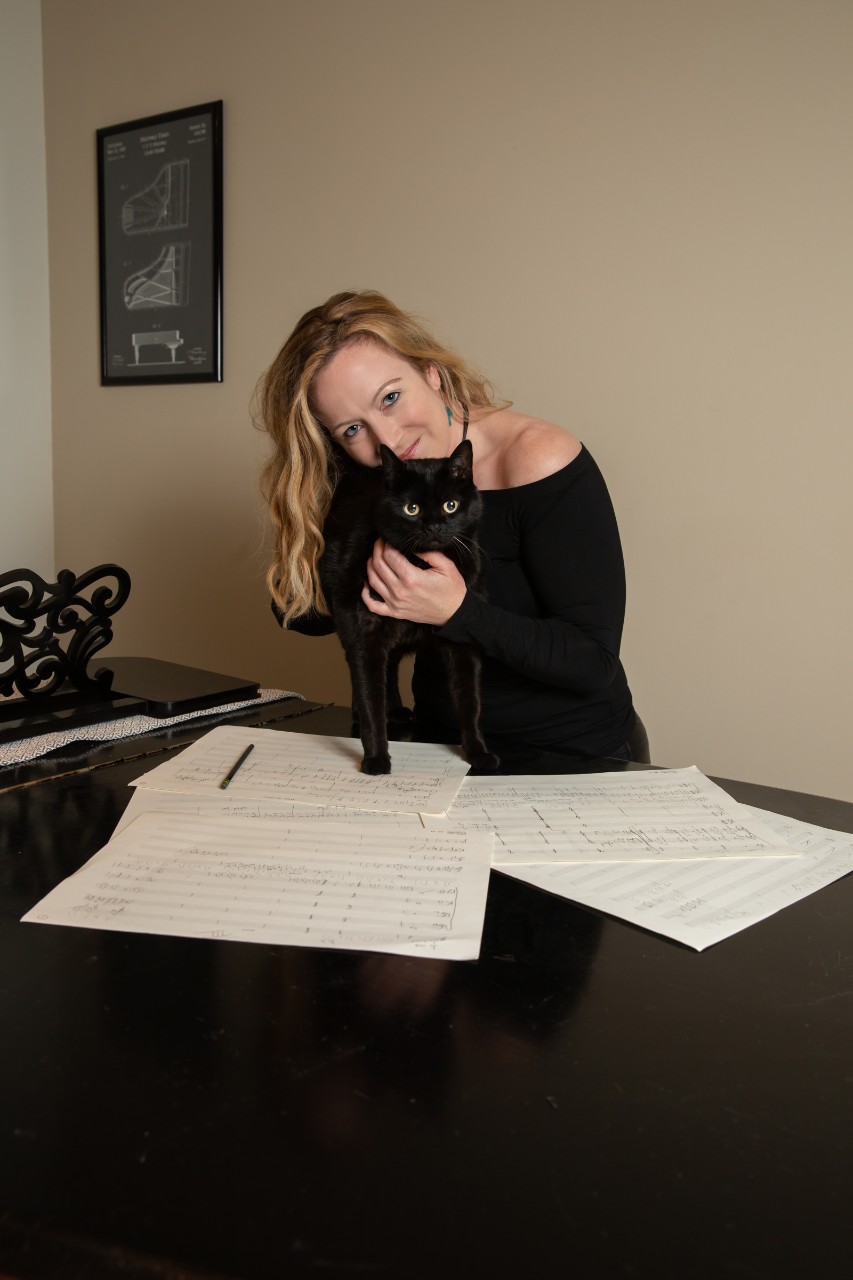

Composer Sarah Hutchings (CCM ’13) looks at COVID-19 and racial injustice as material for the ages

By Cindy Starr

With performance halls closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing requirements, Sarah Hutchings (CCM '13) is feeling like musicians everywhere: homebound. She suffered her share of disappointments when several scheduled premieres of her compositions were canceled this spring, and her regular trips between her home in South Florida and colleagues in New York City are on hold. At the same time, Hutchings finds herself at a thrilling juncture in her career. As both a composer and an editor at a major music company, she is immersed in an explosion of new music erupting from the anxiety of COVID-19, the demands for racial equity, and the long-hidden sorrows exposed by the #MeToo movement.

In her “day job” as publishing editor at the FJH Music Company, Hutchings has a front-row seat to music history as she reviews art music submitted by fellow composers. “There’s so much going on,” Hutchings says. “There’s social upheaval, the pandemic. As composers, we’re very reactionary. We’re asking these important questions — should I react to this? how should I react to this? — as we’re writing. I think in some respects the best thing right now is to listen to and promote the voices of others. I want to give diverse creators the platform to say what they want.”

As the pandemic took hold during the winter and early spring, Hutchings received many new works that reflected feelings of loss and anxiety. Then, following the Black Lives Matter protests and riots sparked by the brutal killing of George Floyd while in police custody, Hutchings received a wave of music that cried out with fury at racial oppression. The art generated by this period of societal upheaval and reassessment, Hutchings believes, will be riveting to audiences when it is ultimately performed.

“I think we as a nation are very beat down by all of this in many different ways, and the reactions are very angry, they’re very anxious, they’re very violent,” Hutchings says. “In a lot of the music I’m getting, you can just see the action on the page and know immediately that something is really going to happen on this page when you play it or hear it. That’s exciting because many of the submissions I received before the virus were very placid.”

Hutchings credits her experience at CCM, where she earned a Doctoral of Musical Arts (DMA) in Composition, with helping her adapt to the COVID-19 era. “I can’t truly express how much my education there meant, because it was so comprehensive on so many levels and gave me so many skills I have to draw on now. There is no siloed career anymore. I consider myself very lucky to have a job in music. Even with this virus that has destroyed some people’s careers, I feel so lucky to be able to do this work that I love.”

Making Music of Her Own

Sarah Hutchings, DMA (CCM, ’13) served as graduate school president while earning her doctorate and remembers that role as one of her most enriching experiences at CCM. Mentored by Robert Zierolf, professor of music theory and history, she developed the administrative skills required for effectively running meetings and negotiating with customers and colleagues. To others whose employment has been impacted by COVID-19, Hutchings says: “Be very real with yourself and sit back and reassess what skills you have. We were so obsessed with career paths prior to this – you know, it must be done this way – and I feel like that has broken down. If you can think back on any of the classes you took, any of the jobs you had, reassess the skills you picked up and how you can translate them into the next opportunity.”

Away from her day job, Hutchings is traveling new paths in a composing career that has seen her works commissioned and performed by the Washington National Opera, the Glimmerglass Festival and members of the Metropolitan Opera, Washington National Symphony, Stuttgart Philharmonic, CCM Philharmonia and Prague Talich Chamber Orchestra. She is working on multiple compositions for small chamber ensembles, which are finding traction with online performances, while embarking on a new concept she has coined “rage music.”

Inspired by #MeToo, female ensembles approached Hutchings about writing music “they can rock out to,” Hutchings says. “There’s a stereotype that female composers will write about flowers and love, and that female ensembles will play it. But they said we just want to rock out. And I said, ‘What if we just got angry together?’ So, I started writing these pieces. They tell me stories about experiences they have had, and I start riffing off of those ideas and coming up with very energetic music.”

In one of her newest compositions, for solo cello, Hutchings explored how women resist sexual aggression and, in the process, launched a new trajectory in her compositional career. During interviews with female survivors of domestic violence, she asked, “What would you want to say to the psychopath in your life? And what, in one sentence, did the psychopath say to you?”

Working at the piano with manuscript paper and pencil, Hutchings notated the syntax of the women’s responses and embedded them in the pitches and rhythms of the music. “So, there’s this wild movement where things are said back and forth,” Hutchings says. “I told them, ‘Even if you don’t read music, I hope I can send you a recording someday so that you know that your statements of resistance against the psychopaths in your life were said somewhere.”

The title of the work, “Psicopata.yellow,” includes Hutchings’s ability to “see” color in sound, a perceptual phenomenon that was confirmed while Hutchings was at CCM. Known as synesthesia – a union of the senses -- it occurs when stimulation of a sensory or cognitive pathway triggers a different sensory or cognitive pathway.

“I didn’t know that synesthesia is a thing,” says Hutchings, who in her previous studies was chided for using a watercolor painting to help describe her ideas for a musical composition. “In Cincinnati, my composition teacher Joel Hoffman, who has synesthesia, tested me on aural skills as part of my entrance exam. He played this tonal cluster on the piano and asked me to identify the intervals. I relaxed and thought about the colors, and I started telling him the intervals. When I made some offhand comment -- ‘It’s kind of this color, it’s purple’ -- he looked at me strangely and said, ‘Do you have synesthesia?’ He explained to me what that was and what that meant, so I found a kindred spirit there, and it didn’t make me feel weird anymore.”

When writing music, Hutchings normally gravitates toward her favorite colors, blue and purple. But for “Psicopata.yellow” (psicopata is Portuguese for psychopath), she infused yellow, which she hears, musically, as “one of the more sickening colors, but with an intense edge to it.”

The work, part of a commission that fell through because of lost funding during the pandemic, is available online for purchase by musicians who wish to play it. In the meantime, Hutchings continues to write and will wait for a day when her new song cycles and other chamber works can be performed. A children’s opera and a mono-drama, an opera with a single singer, are on hold. “Performances or recordings will have to wait, so it’s a time of just writing and writing and writing and seeing what we can do,” Hutchings says. “I’ve had so many requests for new art songs, I could write all day long.”

The UC Alumni Association exists to serve the University of Cincinnati and its 315,000+ alumni across the United States and throughout the world. Learn more about how to stay connected with your alma mater and get involved in more than 50 college-, interest- and location-based alumni networks, including the UC CCM Alumni Network.

Related Stories

UC Day of Giving connects Bearcats across the globe

Event: April 8, 2025 12:00 PM

For 24 hours on April 8-9, this celebration underscores the profound impact of philanthropy and its ability to transform the UC and UC Health community.

REVIEW: CCM's 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' an 'exuberant triumph

March 10, 2025

The Cincinnati Business Courier praises UC College-Conservatory of Music's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. Presented as part of the Opera Series on March 6-9, the production was directed by Robin Guarino and conducted by alumni guest artist William Langley.

Study: Long sentences for juveniles make reentry into society...

March 10, 2025

University of Cincinnati criminologist J.Z. Bennett has a new study that appears in the journal Criminology. The study, "Thicker Than Blood: Exploring the Importance of Carceral Bonds for Those Formerly Serving Juvenile Life Without Parole Sentences," examines the societal barriers to reentry for juveniles who served long prison sentences.