Mentor program to aid Black men in medical school

Retired orthopedic surgeon launches UC effort to reverse alarming trend

The 40-year trajectory for black men practicing medicine in the United States has a downward slope.

In 1978, 1,410 Black men applied to U.S. medical schools, and in 2014 that number was 1,337. During that same time period the number of Black males attending medical school dropped from 542 to 515. The depressing statistics prompted the American Association of Medical Colleges to sound the alarm in a 2015 special report called Altering the Course, Black Males in Medicine.

This continuing trend spurred Alvin Crawford, MD, to ponder who will take the reins in medicine as his generation of trailblazing Black physicians move into retirement. At UC, 26 of 721 medical students are Black men.

Crawford, a University of Cincinnati professor emeritus of orthopaedic surgery and founding director of the Crawford Spine Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, is convinced that mentorship will improve the numbers of Black men becoming successful physicians.

“I am focused on getting Black men through medical school,” says Crawford, also a retired UC Health orthopaedic surgeon. “I am not talking about simply entering medical school, but completing a medical degree and becoming practicing physicians. I think anything we can do to help support these young humans to get to the next level is something that will be valuable for society at large.”

He says diverse physicians can lead to better health outcomes for a diverse population of patients.

“It’s been found that middle-aged and older African-American males, the most vulnerable at-risk group to multiple health disorders, have better outcomes when treated by African-American male physicians whether it be related to trust or compliance or a combination of factors,” says Crawford.

Crawford launched a program at UC this year designed to mentor Black males in medical school. Black Men in Medicine Cincinnati (BMIMC), in its infancy, attempts to pair incoming medical students with older medical students and those who are closer to completing their medical degree with residents and attending physicians. The thinking is that camaraderie, networking and a defined support system might ease isolation and lead to a boost in numbers of Black male physicians.

Crawford is currently recruiting physicians — male and female along with Black and non-Black clinicians — who share his goal without reservation.

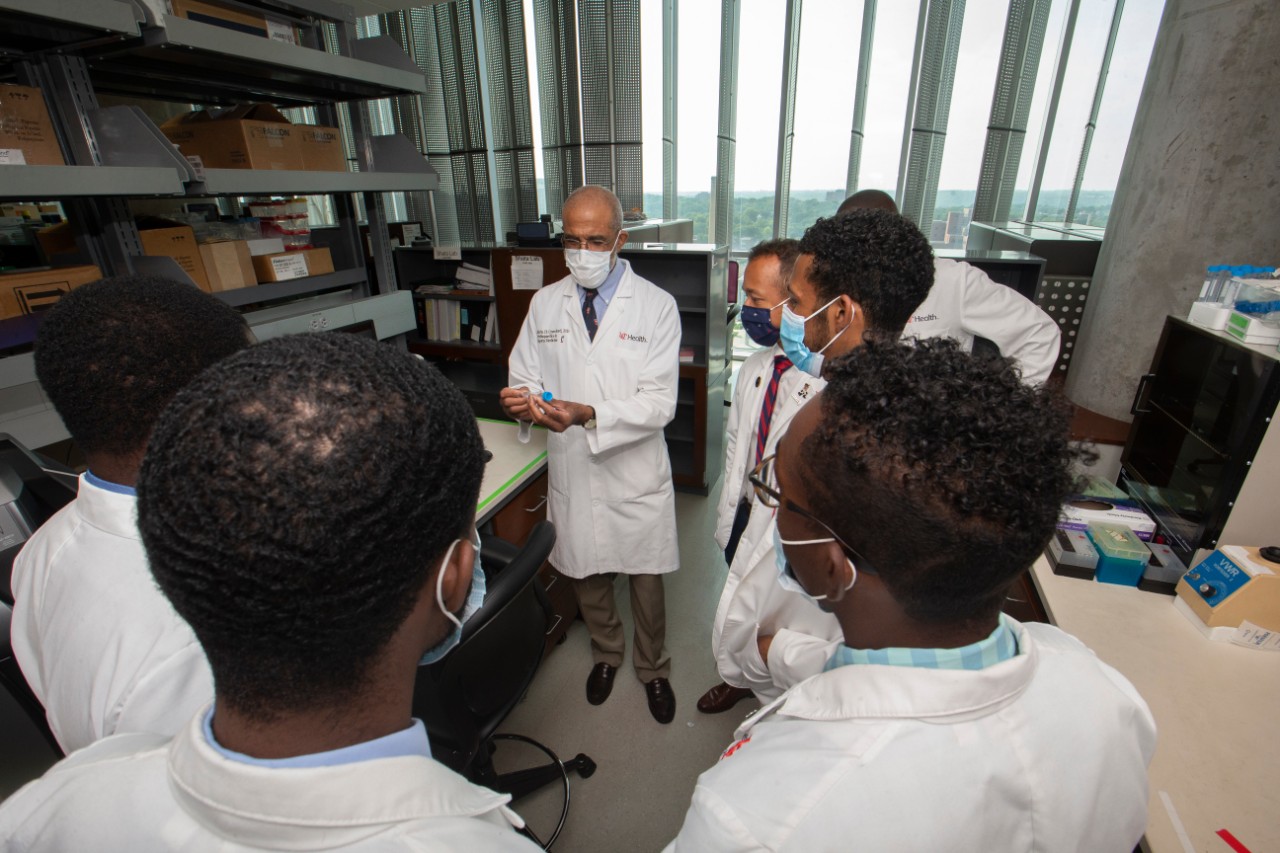

From the rear: Derek Kwakye, MD, Austin Thompson, Michael Deal, Alvin Crawford, MD and Adam Butler are shown in the UC College of Medicine. Photo by Joe Fuqua/UC Creative + Brand.

Crawford is already working with UC medical students — Austin Thompson, Adam Butler and Michael Deal. He’s also mentoring Derek Kwakye, MD, a medical resident at UC Medical Center and a 2018 UC College of Medicine graduate.

“Our mentoring effort has to be cross-cultural and open to all genders,” says Crawford. “The critical issues of Black males have to be the focus of our efforts to make any progress.”

Medical student Thompson, a 2019 UC Arts and Sciences graduate, says he and his fellow medical students have been meeting with Crawford off campus since the summer either remotely or in small groups — masks and social distancing are part of the routine — in the wake of as a result of COVID-19.

Thompson says first-year Black male medical students are the initial target for the BMIMC program, but plans are in place to also reach out to pre-med undergraduates at UC as well as Cincinnati institutions, likely this spring. Additionally, the group hopes to target students in local high schools eventually.

“We are working on how to form correct mentor and mentee relationships,” says Thompson. “That relationship can exist where it is not beneficial. It has to be a very good dynamic for both parties. However, we are catering these relationships more toward the mentees. We don’t want mentors who are too busy. Your mentee should not feel the burden that they are bothering you.”

Thompson says students may find that a medical specialty that interests them might not have Black male physicians represented and available for mentorship, yet, finding supportive allies is crucial.

“A lot of times in medicine there are people in positions we need to connect with that don’t necessarily look like us,” says Thompson. “We want a network that includes individuals regardless of what you look like,” says Thompson. “Our purpose is to increase the numbers of Black males in medicine by increasing recruitment and retention. Any mentor who can align with that mission, we would be happy to have working with us.”

As an undergraduate, Thompson served as a mentor for incoming students. He also benefited from mentorship when deciding to attend medical school. His older brother, who is now finishing dental school, offered important guidance.

“When my brother began college he didn’t start off so hot,” says Thompson. “But from the first day I decided I wanted to pursue pre-med in college, I knew exactly what I needed to do. I would not have known these things if not for my older brother. I knew when to take and prepare for the MCAT and that research, shadowing physicians and volunteering were all necessities for applying to medical school.

“I would not have had anyone to tell me about this if not for my brother,” explains Thompson. “So I want to give back and pass it forward. I want to see other people like me in medical school and eventually complete their medical degree.”

Challenged by medicine: One doctor’s journey

Alvin Crawford, MD, the now retired orthopaedic surgeon and founder of Black Men in Medicine Cincinnati, often contrasts his own journey in medicine with the experience of younger Black men of today. It is part of what drives him.

“My journey has been unique,” says Crawford, a native of Memphis, Tennessee. “I majored in music and didn’t feel I would make it where I was since I was at a state school and not a conservatory. My brother said you like challenges, why not consider medicine?”

Crawford ended up graduating with degrees in music and biochemistry from what was then known as Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University, an all-Black institution and the forerunner of Tennessee State University. He decided to take his brother’s suggestion and pursue medicine and enrolled in Meharry Medical College, one of four historically Black medical schools.

It was 1960 and while legal segregation in the South was starting to fall it wasn’t going away quietly or easily. Crawford completed a quarter at Meharry Medical College when the Tennessee NAACP challenged practices that kept Black residents out of state-supported medical schools. His mother, a nurse, was very proud of her son’s accomplishments, and she worked with a physician who happened to be president of the NAACP, says Crawford.

“My mother could tell you how I was doing, well, anytime you saw her,” says Crawford. “She bragged about how well any of her children were doing. So much so, you would get out the way when you saw her coming.”

The University of Tennessee had been instructed to find a Black student to admit to its medical school, but the retort was they could find none qualified, says Crawford. That’s when the NAACP president approached Crawford’s mom.

“So the doctor said, ‘I hear your son is in medical school,’” says Crawford. “She told him yes, but we had to mortgage the house to get him there.”

The NAACP then submitted Crawford’s MCAT scores and other academic information to the University of Tennessee. The reply was that a qualified Black applicant had been found, but since he was in medical school elsewhere the case for admitting this student was closed, explains Crawford.

“Then we started thinking about it,” explains Crawford. “Meharry is a private school and much more expensive than the University of Tennessee which is a state school. We looked at it, and my mother said, ‘Well, you have always been up for challenges.’”

Crawford left Meharry after his first quarter and interviewed at the University of Tennessee for medical school. His meetings with the dean and provost were far from reassuring.

“The dean said, ‘Son, if my daddy, God rest his soul, could hear me now speaking to you he would turn over in his grave,’” says Crawford.

The dean acknowledged that Crawford graduated top of his class at Tennessee State, but his medical school credits at Meharry would not be accepted by the University of Tennessee which didn’t recognize Meharry as a “qualified accredited” medical school.

Crawford would have to take his initial classes over, and the provost offered a more blunt assessment.

“I think you will flunk out, but if you want to try we are mandated to accept you,” recalls Crawford.

Alvin Crawford, MD, speaks with a group of medical students at the University of Cincinnati. Photo by Joe Fuqua/UC Creative + Brand.

He enrolled but not before explaining to the dean of Meharry Medical College why he was leaving, and that opened another conundrum.

“The dean at Meharry said, ‘Son, you are number two in your class. If you go to the University of Tennessee they will flunk you out and we will lose a good doctor,’” says Crawford.

But that was just part of the problem, the Meharry dean explained. His respectable school trained scores of Black physicians, largely at the time because aspiring Black medical students were denied entry to white state schools across the South. If these students could now attend cheaper state-supported, predominantly white institutions, Meharry would be at risk of losing its best students.

That said, the Meharry dean still understood the need for an end to segregation in medical schools. Crawford settled in for a solitary journey at the University of Tennessee.

“I told my brother ‘you didn’t tell me how much of a challenge this would be,’” recalls Crawford. “Everyone expected me to fail. I never had an adviser and was never allowed to go into the major community hospitals where most of the clinical training occurred in the junior and senior year because they were all segregated. It was quite a unique experience.”

“There were no class parties, no picnics, no social life or get-togethers that I could attend primarily because Jim Crow laws at that time did not allow social integration in any form,” says Crawford.

The young medical student told the University of Tennessee medical school dean during an interview he would pass as long as he was given the same exam as others.

“My mother was a strange lady,” says Crawford. “She said, ‘Never let your oppressor know you are a victim. I don't want any of my children to be victims.’ As a result, there were no outward protests or outcries.

Crawford did graduate, and he was in the top of his class. He went on to train at residencies in the U.S. Naval Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital both in Boston. He received the outstanding resident’s award from the Boston Orthopaedic Club in 1970.

Crawford also did fellowships at the New England Baptist Hospital and Children’s Hospital Medical Center, both in Boston, and at Alfred I. DuPont Institute in Wilmington Delaware. During all of these impressive training Crawford was the only Black male.

Crawford joined the UC College of Medicine faculty in 1977 and continued until becoming an emeritus professor in 2013. Crawford is best-known for his tenure at Cincinnati Children’s where he spent 29 years as chief of orthopaedic surgery. He has also practiced orthopaedic surgery at Good Samaritan, Jewish and Christ hospitals along with UC Health. His tenure in medicine has spanned five decades.

But his experience as a young medical student isn’t one he would want others to repeat. He says that while the legal and social barriers he faced during his day are significantly different, other obstacles for Black men completing medical school remain today.

“The obstacles are binary,” says Crawford. “We like to think that it is about prejudice, and we have to do something about it. There is a decrease in males going into medicine even from legacy families in which the grandfather and father were physicians. The extent for entrepreneurship is dwindling as medicine is now controlled and the indemnity fee for service has more or less disappeared.”

“Black males aren’t applying as much to medical school even though their grades have increased dramatically since the 1970s and 1980s,” says Crawford. “Other fields are now open to these academically-talented individuals today.”

He says the rigors of medical school aren’t insurmountable but that persistence even with a few stumbles is crucial. Crawford, who participates in an academic appeals, review committee for the UC medical school, describes a difference in students who have encountered difficulties and had to repeat courses through summer study or other means. He noticed that when this has occurred for Black students, the paths for Black men and Black women can differ.

“The females will usually trudge persistently along and get it done, but the males will look for other opportunities and leave,” says Crawford. “It is my desire that our mentoring program will give our most at risk group for failure a more nourishing and supportive environment.”

“It’s comforting to think of changing the dynamic of ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’ to ‘I see and will be,’” says Crawford.

Featured image at top: (left to right) Senu Apewokin, MD, speaks with Alvin Crawford, MD, and medical students Adam Bulter, Austin Thompson and Michael Deal. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's medical, graduate and undergraduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Ohio could soon make breast cancer screenings more affordable

May 9, 2025

The University of Cincinnati Cancer Center's Ann Brown was featured in Local 12 and Cincinnati Enquirer reports on a bill introduced by Rep. Jean Schmidt in the Ohio legislature that seeks to eliminate out of pocket medical expenses such as copays and deductibles associated with supplemental breast cancer screenings.

Preparing students for artificial intelligence in education

May 8, 2025

Laurah Turner, PhD, associate dean for artificial intelligence and educational informatics at the University of Cincinnati's College of Medicine, recently joined the For The Love of EdTech podcast to discuss the usage of personalized learning and AI coaches to enhance educational experiences.

UC lab-on-a-chip devices take public health into home

May 8, 2025

University of Cincinnati engineers created a new device to help doctors diagnose depression and anxiety. The “lab-on-a-chip” device measures the stress hormone cortisol from a patient’s saliva. Knowing if a patient has elevated stress hormones can provide useful diagnostic information even if patients do not report feelings of anxiety, stress or depression in a standard mental health questionnaire.