Improbable life story responsible for Law Alumna’s Legal Journey

Judge Marilyn Zayas (Law, '97), the first Latina on Ohio’s Court of Appeals, gives back

By Keith Stichtenoth

“Spanish Harlem”

There is a rose in Spanish Harlem

A red rose up in Spanish Harlem

It is the special one, it’s never seen the sun

It only comes out when the moon is on the run

And all the stars are gleaming

It’s growing in the street

Right up through the concrete

But soft and sweet and dreaming

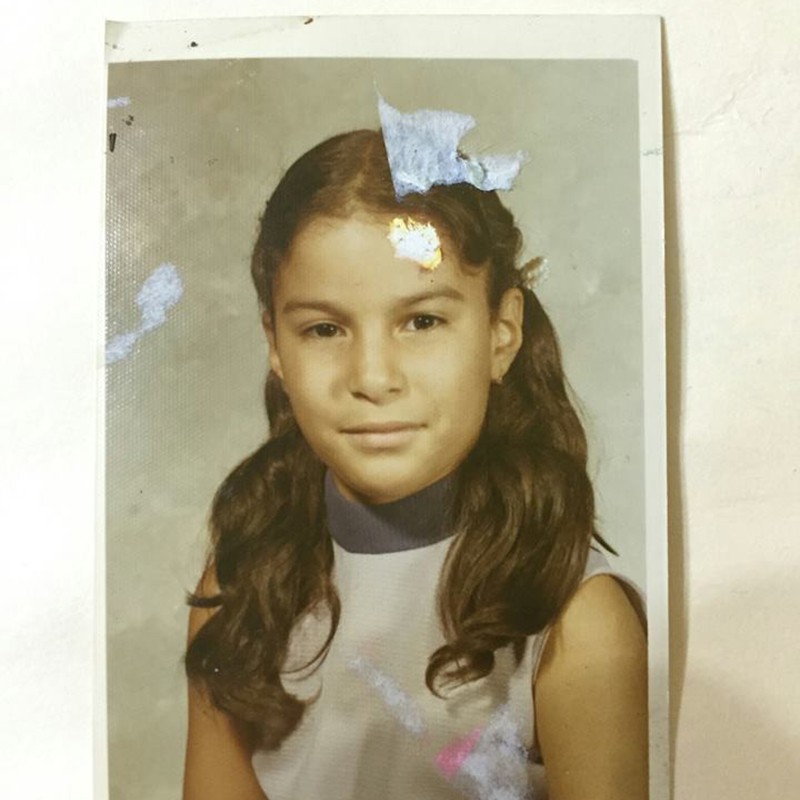

Growing up in East Harlem, young Marilyn Zayas was already forming the perspectives and values that would take her far in life.

In the years shortly after “Spanish Harlem” was recorded by Ben E. King in 1960, Marilyn Zayas was born of Puerto Rican migrants who spoke little English, and she began to grow up in that distinct neighborhood of Upper Manhattan. Given the discrimination facing boys and girls like her, it wasn’t the sort of upbringing that predicted success, let alone the kind for which she was destined.

Little Marilyn Zayas of East Harlem, New York, became Judge Marilyn Zayas, UC College of Law ’97, of Ohio’s First District Court of Appeals in Hamilton County in 2016, elected to fill a vacated seat on the bench. Thus she became the first Latina elected to any Ohio Court of Appeals and the state’s highest-ranking judge of Latino heritage. She was re-elected two years later in a landslide. How in the world did this happen? And why is Ohio fortunate that it did?

In a world where diversity can too often be narrowly defined or appreciated, the presence of Marilyn Zayas on the bench offers unflinching testimony to the notion that there are many ways to reach the same destination. That’s important because there’s a much greater chance that justice will be blind when arbiters of the process understand life and truth through their compelling personal histories and the lessons derived from them.

“When I was in middle school,” Judge Zayas recalls, “my Social Studies teacher showed an old film from probably the ’60s. It said, ‘The typical middle-income family has a house in the suburbs, a car, a dog, and a washer and dryer.’ And I’m sitting there going, ‘Not me, not me, not me, not me.’ Afterward, the teacher explains about blue- and white-collar workers, and says something along the lines of, ‘Some of you may become blue-collar workers someday, but most likely you will not be a white-collar worker.’ And I remember thinking, ‘Well, why not?’”

Not lesser than, not more than

As she grew, the harsh circumstances created by her ethnicity and environment caused young Marilyn to become gripped by two intertwined feelings. The first, she says, was to rebut the illogic: “I had this very strong and innate sense that I’m not lesser than, but I’m also not more than … which then means that you’re not lesser than, or more than. So that’s how I see everyone. I meet people for who they are. They’re not lesser than, they’re not more than — they’re just who they are, right?”

The second takeaway was a sober recognition that she must leave her unproductive environment in order to flourish. Because she saw college as the key to unlock that door, she enrolled at City College of New York. And because she understood her own affinity for the rigors of complicated and structured thinking, she studied electrical engineering at first before eventually graduating with a degree in computer science. Degree in hand, she followed an exciting career opportunity to Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati as an IT manager (“Wow! You can’t get any more ‘white-collar worker’ than that!” she exclaims, recalling middle school).

This doesn’t suggest the specific sort of gray matter one might expect to find adjudicating appellate cases, but it reflects how Judge Zayas processes information, which she turns to the court’s advantage as few of her peers can. “I break down a lot of my cases into flow charts, which come from my computer days. You get to see the connections of everything, and to see if something is missing.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, she also admits to always being able to handle complexity more easily than simplicity. She calls it her “engineering brain” and illustrates through the old “forest for the trees” analogy. “I’m pretty good at seeing both the forest and the trees, but really I’m about seeing the moss growing under the trees, and recognizing why the moss is on one side of the trees and not the other.”

It’s a good thing she relishes complexity and detail. The First District Court of Appeals receives civil and criminal cases from all trial courts in Hamilton County — domestic relations, foreclosures, contract issues, insurance claims, wills, adoptions, car accidents, murders and more. Anytime a case has been decided by a lower court and someone feels something went wrong, an appeal sends the case to the appellate court (69 judges statewide). When cases reach Judge Zayas, they will be greeted by a dispassionate, fact-driven perspective free of pre-judgment or bias. It’s the very conscious antithesis of the judge’s youthful recollections of East Harlem.

“It’s not about getting caught up in the emotions of the case; it’s about getting caught up in the law,” she says. “I don’t come to a case thinking, ‘This is what the answer should be, or this is the rule of law I would like to create.’ Rather, let me and my team do research — and I think people would be shocked at the amount of time we spend doing research. Let us review the record, go through transcripts and exhibits and motions that were filed, and make sure we leave no stone unturned.”

A responsibility to help others

Verjine Adanalian, Law ’17, right, has become great friends with her mentor, Judge Zayas, Law ’97.

Given the road she has traveled, it’s not surprising that this mother of three adult children feels an enormous responsibility to help younger members of her broader legal family as they embark on their own careers. After her election in 2016, Judge Zayas created the Educating Tomorrow’s Leaders program in which high school, college and law students are invited to the Court of Appeals to interact with judges and attorneys, learn about the law, and allow themselves to dream about where their aspirations might take them. She has also taught at the UC College of Law and spoken at many events within the legal community, including the commencement ceremony for UC Law’s Class of 2017, at which she was honored with the school’s Nicholas Longworth III Alumni Achievement Award. One of the graduates that day was a first-generation American whose parents are Armenian. Verjine Adanalian found herself incredibly inspired by Judge Zayas’ remarks.

“I remember literally sitting on the edge of my seat and feeling like I identified with someone who I admired greatly,” Verjine recalls. “My grandmother later said that hearing Judge Zayas’ story made her believe that anything could be possible for me, too.”

The desire to share this feeling and connect with the judge led Adanalian to reach out to her. She had passed the bar exam by this point but hadn’t yet found the right first job. There was a networking event on a bitterly cold February evening and Adanalian almost didn’t go, but she was rewarded by finding Judge Zayas there, then by overcoming her anxiety to approach the judge — a move that forever changed both women.

“When I met her,” says Judge Zayas, “I knew in my heart that I needed to know, ‘Who is Verjine? What are her goals? What can I do for her?’ Because as we establish our relationship, that’s my goal and responsibility as a mentor — to help them become more successful than they would have been otherwise.”

As their mentorship and friendship quickly grew, Judge Zayas helped provide Adanalian with exposure within the judge’s network along with responsibilities that would cultivate the skills Adanalian needed to gain the type of job she wanted. Before long, a fellowship opened at the Ohio Justice and Policy Center working with trafficking victims. It became a perfect example of the value of insightful mentoring and courageous personal growth.

“What makes Judge Zayas special as a mentor is how generous and thoughtful she is,” Adanalian says. “I’ve appreciated how she has fostered my growth and empowered me to be confident and bold. Her authenticity makes it easy to confide in her and to trust that you’re safe.”

Case in point: Adanalian wasn’t going to apply for the position, believing she wasn’t qualified and that she should spare herself the rejection. Judge Zayas saw it otherwise and said so, knowing that she had been advising Adanalian on specifics that strengthened her marketability. Sure enough, she bested her competition and remains in the job today. She also teaches at Wright State University, and in seeking out opportunities to converse with bar associations throughout the state, she’s becoming a go-to expert in Ohio on the unfortunate topic of human trafficking.

Unequal circumstances, equal before the law

Judge Zayas became the first Latina to sit on Ohio’s Supreme Court in 2018, temporarily replacing a recused justice.

As Judge Zayas considers her journey and her opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others, she feels a variety of emotions — but mostly she’s simply thankful.

“When I reflect on being elected and then re-elected to the bench, I feel an incredible amount of gratitude. I came literally out of nowhere, and yet the community entrusted me with this seat and its responsibility. People saw something in me, something different. And yet this has little to do with just Marilyn Zayas — it’s far bigger and more meaningful than that.”

A unique personal journey and its sometimes painful lessons created the unusual opportunity for all of this to happen — for the judge and everyone she influences. And she recognizes she defied some long odds to do so, becoming the first Latina elected an appellate judge in Ohio, the first elected to any position in Hamilton County, and the first to ever sit on the Ohio Supreme Court when she temporarily replaced a judge who was recused. But again, diversity goes way beyond that.

“How many people in IT have ever made it to the bench?” she asks. “When I came out of law school, I was an intellectual property litigator, and coming to the bench from that specific field is more rare than a Latina doing it. What’s the likelihood that someone born and raised in New York City and who came to Cincinnati in their 20s would even be elected? So the levels of diversity here are kind of crazy — in a good way!”

The UC Alumni Association exists to serve the University of Cincinnati and its 315,000+ alumni across the United States and throughout the world. Learn more about how to stay connected with your alma mater and get involved in more than 50 college-, interest- and location-based alumni networks, including the UC College of Law Alumni Network and the UC Latino Alumni Network.

Related Stories

New Dungeons & Dragons ethics seminar takes flight

July 7, 2025

On a blisteringly hot summer day, laughter echoed through the cool, damp basement of the Avondale branch of the Cincinnati Public Library. Young teenagers huddled around a table littered with pencils and paper, rolling dice and bonding over a game of Dungeons & Dragons. University of Cincinnati undergraduate student Charitha Anamala sat behind a trifold card with a blazing red dragon on it, serving as the group’s Dungeon Master (DM) or campaign organizer. Within the fantasy setting she described, it was hard to tell the adventure was a lesson in ethics.

‘Blind Injustice’ performance features Cuyahoga Falls singer

July 7, 2025

The Akron Beacon Journal showcases the contemporary opera, "Blind Injustice," which tells the story of six Ohio Innocence Project exonerees. OIP is based in the University of Cincinnati College of Law.

Making sense of the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings during its...

July 1, 2025

Anne Lofaso, a professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Law, discusses rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court with WVXU's Cincinnati Edition.