UC contributes to global plant database

The National Science Foundation project will open new research opportunities

The University of Cincinnati is sharing its massive collection of plants in a new digital database sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

UC joins two dozen other institutions in contributing to this enormous catalog of lichens and bryophytes, the group of small green plants that include mosses.

“What I find interesting about them is the unseen diversity that’s right under our toes,” said Eric Tepe, a botanist and director of UC’s Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium.

UC’s herbarium on the top floor of Crosley Tower is a repository of 127,000 plant specimens collected from around the world. UC has already cataloged much of its collection in one botanical database — a sort of “wood wide web” called iDigBio.

“So many collections are made up of the more obvious and charismatic flowering plants,” said Tepe, an assistant professor of biology in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Our collection is unusual in that about half of the specimens are bryophytes and lichens and the other half are vascular plants.”

The project demonstrates UC's commitment to research as described in its strategic direction called Next Lives Here.

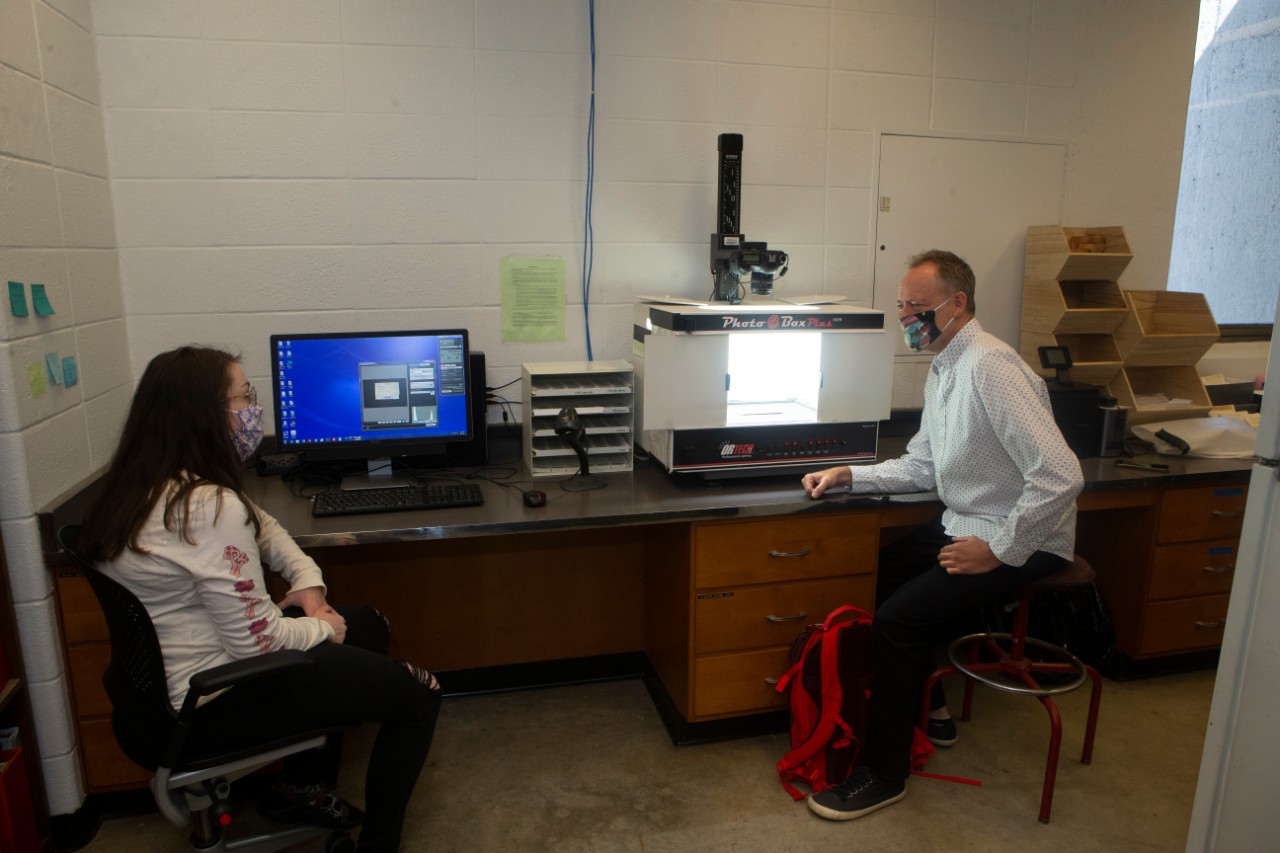

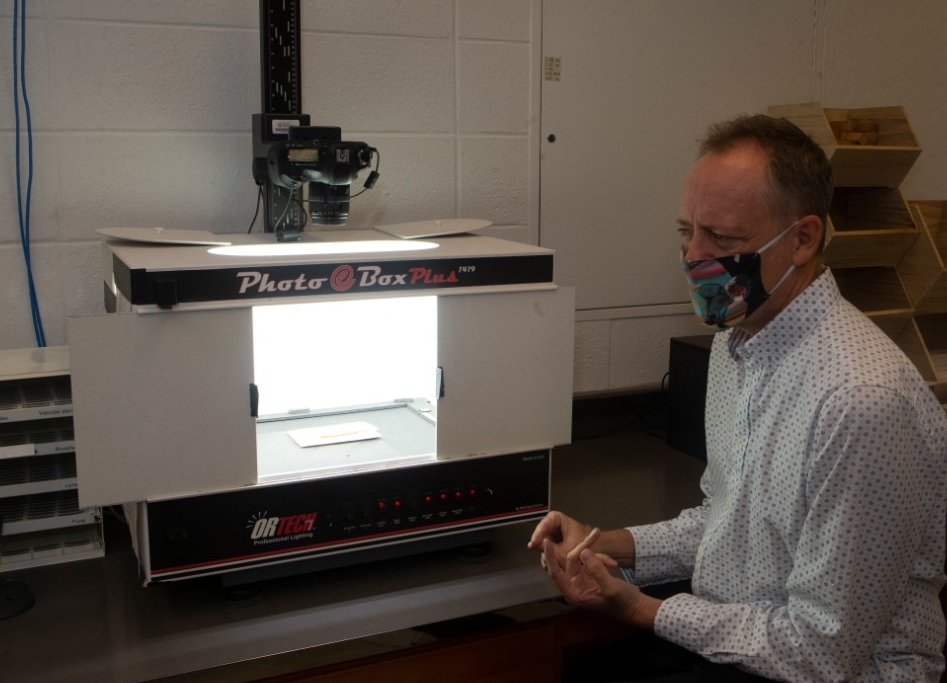

UC assistant professor Eric Tepe uses a lightbox to capture images of specimens from UC's herbarium. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

UC undergraduate student Olivia Leek has been working on the NSF digitization project since July. In some cases, she has to transcribe labels that botanists scrawled on collection envelopes nearly 100 years ago.

UC student Olivia Leek. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

“Some people have very bad handwriting,” she joked.

Leek said she has an appreciation for UC’s collection.

“Mosses have a lot of uses in culture, too. I was reading how Native Americans used them as bed mats and diapers,” she said. “This is my first research project in my undergrad career. I feel it’s nice to be able to contribute. I feel validated.”

Mosses represent the earliest terrestrial plants on the planet. More than 470 million years ago, ancient mosses and their relatives began to fill the air with the oxygen that makes our atmosphere breathable today, according to the magazine New Scientist.

UC's Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium has more than 127,000 plant specimens from around the world. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

UC’s collection of bryophytes includes bizarre plants called hornworts and liverworts. Bryophytes don’t have roots or seeds. Instead, they reproduce through spores like fungi.

They are found virtually everywhere, even in inhospitable places like the Sahara Desert and Antarctica. But they’re far more common in wet places like rainforests. Scientists can use bryophytes as a bellwether for pollution, Tepe said.

“They’re incredibly important ecologically. They’re especially sensitive to acid rain and air pollutants, which makes them early indicators of degrading environmental conditions,” Tepe said.

“In clean areas, you see a huge diversity of species. When you start to get contaminants in the air or water, species begin to drop out. And which species and how many go can tell you a lot about the quality of the air and water in the area.”

UC students conduct botany fieldwork at UC's Center for Field Studies. Photo/Ravenna Rutledge/UC Creative + Brand

Funded by a three-year $3.6 million NSF grant, UC and its partner institutions are building a giant digital collection of bryophytes and lichens.

“Digitization is a game changer,” Tepe said. “For centuries, natural history collections have been locked up in museums, available only to a handful of visitors. Large-scale digitization efforts, like this project, open the museum doors to the world, making specimen data and, in many cases, images freely available to everyone.”

The University of Tennessee at Knoxville is leading the project.

UC has an incredible bryophyte collection and I am really grateful to be able to work with it. Bryophytes are fascinating.

Laurie Heldman, UC student

“Natural history collections are a physical record of our planet’s biodiversity across space and time,” said Jessica Budke, the principal investigator for the project and director of the herbarium at UTK.

“These specimens not only serve as records of the past, but they are a critical resource for our future. They help us to answer important questions surrounding invasive species and conservation biology and to describe species that are new to science.”

The grant will pay to create a new online catalog of 1.2 million lichen and bryophyte specimens from the participating universities’ herbaria. UC’s collection alone features more than 50,000 specimens.

Margaret H. Fulford, the UC herbarium’s founder and namesake, was an expert in bryophytes. She began UC’s collection in 1927 and supervised it until her retirement in 1974.

“She was the world authority on Latin American liverworts. During her time as curator, she accumulated the majority of UC’s liverwort collection,” Tepe said.

Her successor, UC botanist Jerry Snider, was a moss expert who turned UC’s moss collection of a few hundred specimens into a repository of more than 24,000 specimens when he retired in 2001.

“As a curator, I am thrilled that the specimens held in the herbarium at the University of Cincinnati will be available to anyone working with these fascinating organisms,” Tepe said.

Tepe, too, is adding to UC’s collection with his fieldwork. He is adept at finding the tiny plants during his field surveys.

“They’re hard to find. They’re small. They’re inconspicuous,” he said.

And UC’s collection has a surprising geographic reach. The herbarium has specimens from as far away as the Indian Himalayas.

UC biologist Eric Tepe holds up an envelope containing a specimen collected in 1960 by Towson State College in Maryland. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

Tepe’s biology students are taking advantage of the resource for their studies.

UC student Laurie Heldman is working with bryophytes from the Amazon rainforest gathered in the 1950s by pioneering UC ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes.

“UC has an incredible bryophyte collection and I am really grateful to be able to work with it,” Heldman said. “Bryophytes are fascinating. I am really impressed with how many people are so passionate about them, even though most people don’t know much about them.”

The biggest benefit of this digital catalog is to open the door to future research by botanists around the world. Already, UC’s collection has been cited in six new articles in research journals in as many years, he said.

“So it’s put us on the map in a really cool way,” Tepe said.

Until recently, if researchers wanted to examine a collection, they would have to pay travel expenses to visit the institution. And lending samples to other institutions carries its own risks. Australian customs officials in 2017 destroyed 200-year-old specimens from Paris that were requested by the Queensland Herbarium in Brisbane.

“Digitization levels the playing field for researchers around the world, making it possible for scientists from countries with limited resources to carry out important work,” Tepe said.

Featured image at top: UC student Olivia Leek, left, and UC assistant professor Eric Tepe use a lightbox to photograph specimens for a new National Science Foundation project. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative + Brand

UC assistant professor Eric Tepe stands in front of a cabinet containing specimens from UC's Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Creative + Brand

Impact Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Stay up on all UC's COVID-19 stories, read more #UCtheGood content, or take a UC virtual visit and begin picturing yourself at an institution that inspires incredible stories.

Related Stories

RevolutionUC hackathon highlights student ingenuity at 1819

March 14, 2025

The University of Cincinnati’s 1819 Innovation Hub recently hosted three of the Queen City’s premier hackathons: RevolutionUC, MakeUC and UC Startup Weekend.

UC chief digital officer named 2025 Ohio ORBIE Awards Enterprise...

March 14, 2025

University of Cincinnati’s Vice President & Chief Digital Officer Bharath Prabhakaran was named 2025 Ohio ORBIE Awards Enterprise CIO of the Year. This award recognizes Bharath’s leadership in digital transformation, fostering innovation, and enhancing student success at the University of Cincinnati.

Cold-blooded and they make great friends

March 13, 2025

First-year student Josh Lantz starts a Herpetology Club at the University of Cincinnati.