Dr. Art Evans recalls 1968 Mexico City Olympics

Emeritus OB/GYN professor was rower on U.S. Olympic team

The threat of COVID-19 that athletes at the Tokyo Olympics currently face reminds Art Evans, MD, of the challenges of high altitude sickness that athletes faced during the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. Fifty-three years ago, many athletes battled light-headedness, fatigue and severe shortness of breath due to Mexico City’s 7,600-foot elevation. In extreme cases, some suffered high altitude pulmonary edema.

Evans, College of Medicine Class of 1974 and recently retired chair of the UC Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, knows firsthand. He was a member of the U.S. Olympic eight-man crew rowing team in Mexico City and spent a night in the hospital with high altitude sickness after his first rowing event there.

Evans began suffering from the effects of altitude sickness within a week of arriving in Colorado, where the team trained before going to Mexico City in October 1968. At the time, it was thought that six weeks of training in the higher altitude of Gunnison would properly prepare the athletes. Evans says that today, athletes would train for at least three months to prepare for high altitude competition. While in Colorado, Evans was not able to train normally and it was unknown whether he would be able to serve as stroke of the eight-man boat in the Olympics competition. The stroke sits facing the coxswain and is the most important rower as he is responsible for setting the pace and making strategic race decisions.

The team’s first heat in the 2,000 meter race was Sunday, Oct. 13, 1968, on Lake Xochimilco, and fortunately, Evans felt well enough to participate. The winner would qualify for the Olympic finals on Oct. 19.

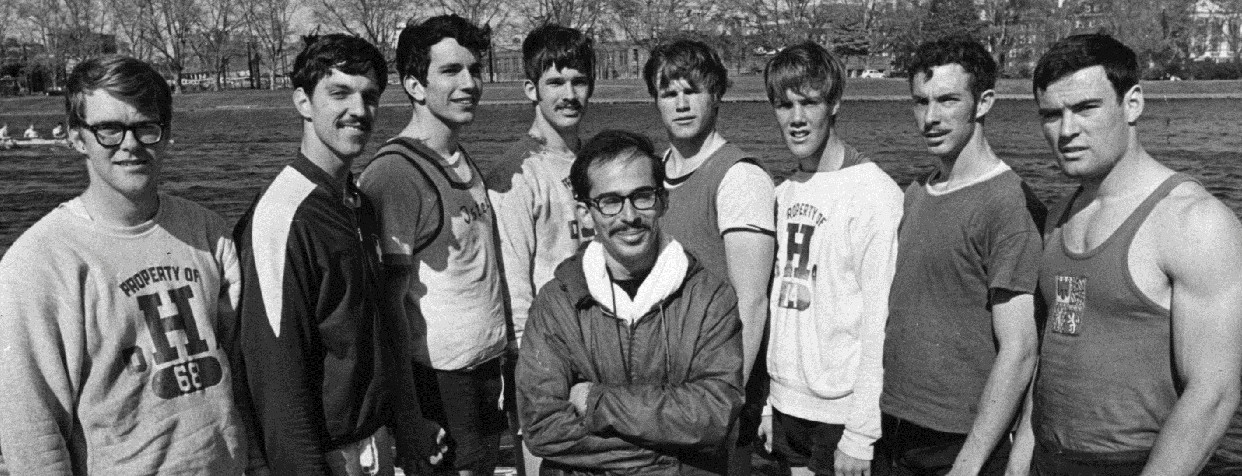

The 1968 U.S. Olympic eight-man rowing team. Dr. Art Evans is in the back row, second from left.

“When we got into the first race, I did fine for the first 1,500 meters,” Evans recalls. “We were half a boat length ahead of everyone and that’s when we usually turned it on and pulled away from everybody. At that point it was a like a dark cloud came down over my vision and I remember the Great Britain boat started moving on us. Normally I would have responded and picked it up and moved away from them and I just kind of watched them move on us. It didn’t really register. I don’t remember anything else. I went into high-altitude pulmonary edema and was in really bad shape. I finished the race, but I don’t remember finishing it and I was at that point close to getting intubated because I was in such respiratory distress.”

Evans spent a night in the hospital and was not able to compete again in the 19th Olympiad.

The U.S team finished fifth among the six boats in the heat, only beating Great Britain. New Zealand, East Germany, Russia and Holland finished ahead of the Americans, in that order.

“It was my fault. Essentially, I passed out. I finished the race rowing but I don’t have any recollection,” Evans says.

Coverage of the race in the Oct. 14, 1968, edition of the Boston Globe pointed to the team’s failure to adjust to the altitude, but did not specifically call out Evans’ illness. It also noted how Steve Brooks, the No. 3 rower, had a “cranky back,” and No. 2 rower, Cleve Livingston, had been hit by the flu the previous day “Each insisted he was all right although this was a tired crew physically and emotionally when it struggled across the finish line,” Globe reporter John Ahern wrote.

Evans also had been dealing with an allergic reaction to the treatment he was receiving for his altitude sickness. Most of the media coverage before the race questioned how the young American team would fare against more experienced, older rowers representing other countries. The American team was Harvard University’s eight-man crew with an average age of 20.6 years old. Evans was just 21.

The team qualified for the finals in the repechage that pitted boats which lost in the first heats. In the finals, the U.S. finished last of the six teams, with West Germany taking gold, Australia silver and Russia bronze.

Evans says that altitude sickness happened to numerous rowers. The bowman of the Swiss two-man team, which had not lost a race since winning the gold medal in the 1964 Olympics, almost died on the Mexico City course before he could be removed from the boat.

The 1968 Harvard eight-man rowing team, which would represent the U.S. in the Mexico City Olympics. Dr. Art Evans is the first rower at right.

He recalled how he developed symptoms within the first week of arriving in Colorado to train before the Olympics.

“As time progressed and the rest of the guys were able to accomplish the usual kind of workout, I just couldn’t do it,” Evans says. “I had always been able to do any workout and work at a very high level and all of a sudden, I just couldn’t do it. It was very scary because I had always been able to push through anything. I just couldn’t do it. Today they would have addressed and solved this problem, but exercise physiology was much more rudimentary in 1968.”

Unlike most of today’s athletes who begin training in their particular sport at a very young age, Evans’ path to the Olympics only took him three years. A standout football player at Mariemount High School and the son of Arthur Evans Jr., MD, professor and head of urology at the College of Medicine, Evans attended Harvard with the intention of continuing to play football. But when he got to college, he decided to focus his efforts on academics. Early in his first semester, however, he and his roommate were invited to the Harvard boathouse where they started to row, something he had never done before. His roommate stopping rowing after three weeks but Evans continued.

Evans laughed and said “I didn’t want to devote the time to playing football, and I ended up in a sport that was 10 times more demanding on my time. I liked the essence of the sport that was demanding physically and required a lot of intense focus and you made really deep and intense friendships with people.”

Evans rowed on the freshmen boat for a year and then moved up to the Harvard varsity boat his sophomore year. After an intense competition, Harry Parker, the leading crew coach in the country, selected Evans for the stroke position. He recalls that it took two years to develop the level of conditioning necessary to compete in collegiate and then Olympic rowing. The sport requires strength, balance and endurance and it works every muscle in the body, he says.

Evans believes Olympic organizers were remiss in planning for the Mexico City Olympics and failed to take the city’s high altitude into consideration.

Art Evans, MD

“The COVID situation is an analogous unknown to the altitude situation that we faced,” he says. “Even today they talk about not embarrassing the host nation and committee. If you look overall in the Olympic events in 1968, there was virtually no discussion about altitude and I think in the background there was a real push to suppress discussion of the altitude as a negative factor, to not be finger pointing, embarrassing to both the host nation and to the International Olympic Committee. There really should have been a huge uproar and investigation about why the International Olympic Committee would agree to host an Olympics at that altitude. Nobody’s competing at that altitude unless you’re in winter alpine sports. So why would you suddenly take athletes who are competing at sea level and put them at an altitude that has a major impact on performance. There was virtually no discussion about that. It’s a statement about the time. It was a totally different time.”

While Evans is disappointed that the team did not win the gold medal he is happy how his life played out. He finished his undergraduate education rowing for one more year at Harvard and as the stroke of the U.S. national eight team before moving on to medical school. Five of his teammates from the 1968 Olympics continued rowing and again represented the U.S. in the 1972 Olympics, winning the silver medal.

In the fall of 1970, Evans entered the College of Medicine and graduated with the Class of 1974. He would go on to do his OB/GYN residency at the Mayo Clinic and maternal-fetal medicine fellowship at the University of California-Irvine. With a career in academic medicine, he became the chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center before returning to Cincinnati in 2007 to chair the UC Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. He stepped down as chair in 2019 and retired as emeritus professor in July 2021.

“My wife often tells me ‘It’s a great thing you didn’t win the gold medal because it would have changed your life in a way that would have been far different from where you are today,’” Evans says with a chuckle. “She probably has better insight on this than I do. If we had won the gold, the pressure would have been to continue rowing. I was only 21 at the time and rowers typically reach their peak at about 25 to 28. The pressure would have been on us to continue competing. I probably would have deferred medical school and I might well have ended up going into coaching rather than medicine. Most importantly, while I was recovering from altitude sickness after the Olympics and before returning to Harvard for the winter semester, I started dating my wife, Catherine. She claims that never would have happened if we had been successful in Mexico City. We have nine grandchildren and just celebrated our 50th wedding anniversary, so how can I disagree with her.?”

Evans did not compete in rowing after he left Harvard, but he still rows on a home rowing machine, putting in 10,000 meters each day.

Feature photo: the 1968 Harvard eight-man rowing team, which would represent the U.S. in the Mexico City Olympics. Dr. Art Evans is at left.

Related Stories

UC professor Ephraim Gutmark elected to National Academy of...

December 20, 2024

Ephraim Gutmark, distinguished professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati, was elected to the 2024 class of the prestigious National Academy of Inventors.

UC study examines delivery timing in mothers with chronic...

December 19, 2024

In a study recently published in the journal O&G Open, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine physician researchers found 39 weeks of gestation is optimal for delivery in mothers with chronic hypertension.

Winter can bring increased risk of stroke

December 18, 2024

The University of Cincinnati's Lauren Menzies joined Fox 19's morning show to discuss risk factors for stroke in the winter and stroke signs to look for.