UC maps the long road for HIV patients

Many patients in Sub-Saharan Africa have to drive more than an hour to get health care

Many patients living with HIV in rural Africa are not receiving regular treatment, despite recent efforts to increase access to health care across the continent.

Researchers with the University of Cincinnati found that 28% of HIV-positive patients 15 and older in eastern and southern Africa and 42% of patients in western and central Africa were not receiving the latest anti-retroviral therapy.

The findings demonstrate the challenges of serving rural populations, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study concluded that improving access to health care is key to reducing the incidence of HIV.

“A large number of people living with HIV in Africa are lacking treatment and care, particularly the latest antiretroviral therapy, due to limited health-related resources,” said Hana Kim, a doctoral student in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences and lead author of the study.

The study was published in the journal PLOS Global Public Health.

UC doctoral student Hana Kim worked with researchers around the world to map health care disparities in Africa. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative + Brand

Africa is big — far bigger than you might realize. The United States could fit inside Africa three times over. In fact, Africa could hold the United States, China, India and Mexico with room to spare. Providing health care to rural populations is an especially daunting challenge, Kim said.

African countries have not only an outsize geography but also disproportionate rates of HIV compared to global averages. HIV infection remains a leading cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest number of new infections in the world.

“HIV prevalence, or the rate of infections, is extremely high in the Africa region despite a lot of mitigation efforts focused on Africa for several decades,” Kim said.

The United Nations Program on AIDS in 2015 announced a goal of boosting HIV diagnosis and treatment by 2020 in a bid to end the scourge of AIDS by 2030. The effort recognized that expanded access to treatment is crucial for success.

“Access to the nearest healthcare facility is one of the most important measures for HIV treatment success,” said co-author Diego Cuadros, an assistant professor and director of UC’s Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab.

“Viral suppression is very important because these HIV positive individuals with viral suppression are healthy individuals that also are not infectious and thus do not transmit the disease,” he said.

In contrast, those who are not receiving treatment are far more likely to get sick or even die and to transmit the disease to others, he said.

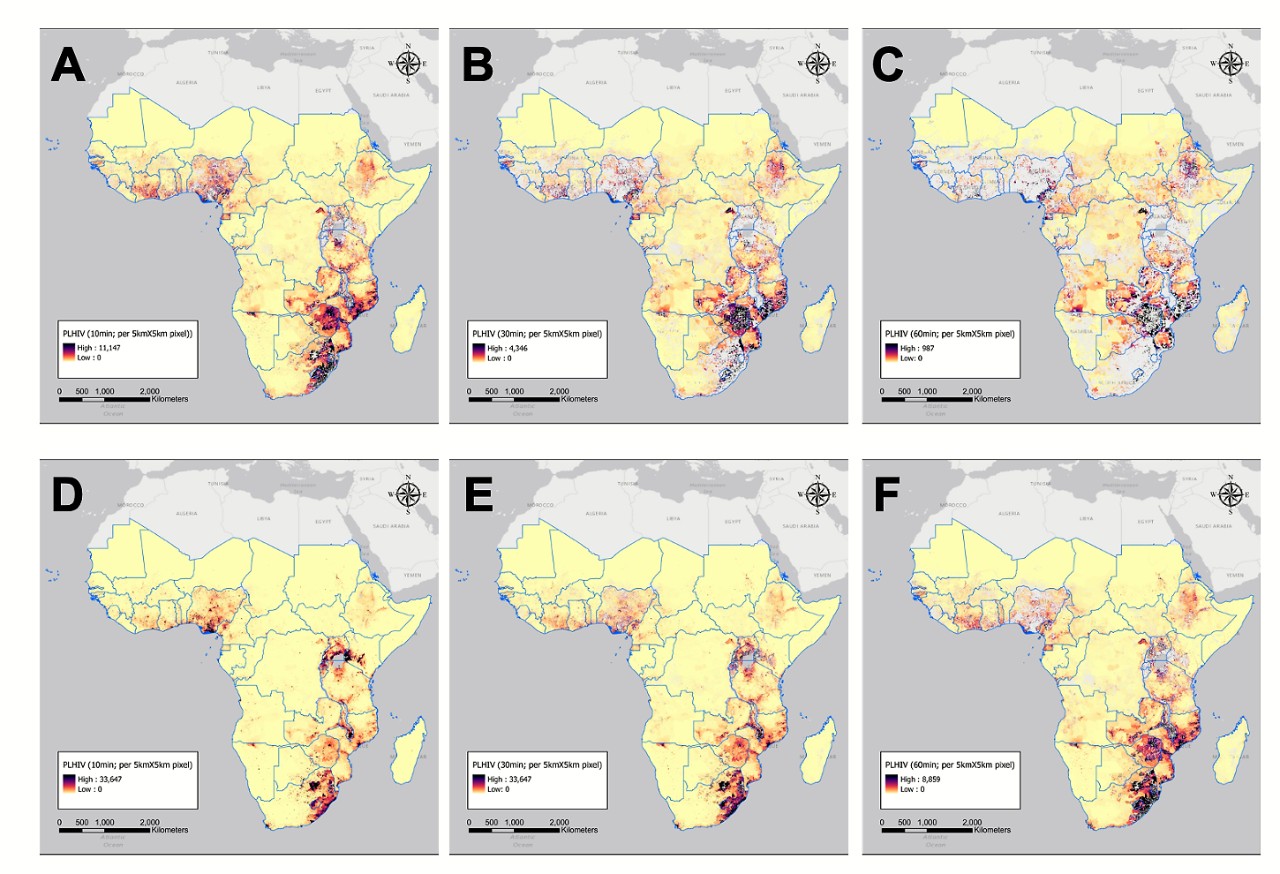

Maps of Sub-Saharan Africa show HIV-positive populations living within a 10-, 30- or 60-minute walk or drive to the nearest health care provider: A. 10-minutes by car. D. 10-minute walk. B. 30-minutes by car. E. 30-minute walk. C. 60-minute drive. F. 60-minute walk. Graphic/UC Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab

The study is an international collaboration between UC and scientists in Zimbabwe and Dubai and Oregon State University.

For her doctoral program, Kim has been examining vulnerable populations living in areas underserved by health care providers. Kim said identifying critical issues such as accessibility to health care is the first step to solving them.

Researchers created maps of sub-Saharan Africa identifying populations living within a 10-, 30- and 60-minute walk or drive. They found that 1.5 million people living with HIV lived more than an hour’s drive from the nearest health facility.

It is expected that health outcomes linked to HIV have worsened during this past year in Africa.

Diego Cuadros, UC's Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab

The study identified disparities in the availability of care across countries. People living in more than 90% of Sudan and Mauritania had to drive more than an hour for health services.

In 17 countries, about half of the population with HIV live in places with limited access to health care, the study found.

And in Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi, almost nobody has to drive more than an hour to the nearest clinic, doctor’s office or hospital for treatment.

The study concluded that expanding health care in these underserved communities could improve not just HIV response but the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health issues as well.

“The massive global health crisis of COVID-19 and associated travel restrictions have presented enormous challenges for accessibility to health care for people living with HIV,” the study found. “Unfortunately, people living with HIV are at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and they suffer more acute symptoms than the general population due to having a weakened immune system and lacking access to health services.”

Diego Cuadros, director of UC's Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab, spent the past year tracking COVID-19 across Ohio and other parts of the world. Students in his lab have studied malaria, hepatitis C and the opioid crisis, among other pressing public health issues. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Another consideration is the transportation infrastructure in rural Africa. Kim said public transportation is not readily available in some rural areas while storm-damaged roads and bridges can temporarily limit access. Mobile health care has often filled the void in these areas, she said.

“This strategy has already worked in some countries in Africa such as Malawi and South Africa,” Kim said.

Faculty adviser Cuadros said the pandemic has disrupted many of these mobile strategies over the past two years.

“It is expected that health outcomes linked to HIV have worsened during this past year in Africa,” Cuadros said.

Kim said she plans to build on the study to examine the spatial prevalence of other infectious diseases in underserved areas.

“I am very excited that I have lots of potential opportunities to build my research path, and many thanks to my adviser who always encourages my research,” she said.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Featured image at top: Neighbors clear a road in rural Uganda after heavy rains caused overnight mudslides. An international study led by the University of Cincinnati found that many rural Africans live far from the nearest health care provider. Photo/Michael Miller

UC doctoral student Hana Kim conducts research in UC's Health Geography and Disease Modeling Lab. Photo/Jay Yocis/UC Creative + Brand

UC's influence in Africa

UC College of Nursing student Sabrina Bernardo examines a patient in a makeshift health clinic set up in a schoolhouse in rural Tanzania as part of UC's partnership with Village Life Outreach. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Creative + Brand

University of Cincinnati students and faculty are making a big difference around the world. Here are some of their stories.

Become a Bearcat

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

RevolutionUC hackathon highlights student ingenuity at 1819

March 14, 2025

The University of Cincinnati’s 1819 Innovation Hub recently hosted three of the Queen City’s premier hackathons: RevolutionUC, MakeUC and UC Startup Weekend.

UC chief digital officer named 2025 Ohio ORBIE Awards Enterprise...

March 14, 2025

University of Cincinnati’s Vice President & Chief Digital Officer Bharath Prabhakaran was named 2025 Ohio ORBIE Awards Enterprise CIO of the Year. This award recognizes Bharath’s leadership in digital transformation, fostering innovation, and enhancing student success at the University of Cincinnati.

Cold-blooded and they make great friends

March 13, 2025

First-year student Josh Lantz starts a Herpetology Club at the University of Cincinnati.