UC engineers a quieter future for drones, flying cars

What happens if a disruptive technology literally disrupts daily life?

One obstacle to realizing the dream of flying cars is noise — imagine 1,000 leaf blowers intruding over your backyard barbecue.

It’s not just flying cars but drones as well. Complaints about the high-pitched keening of propellers could lead to restrictions or regulations that could hamper the growth of a new commercial drone industry.

University of Cincinnati aerospace engineering students are studying solutions to dampen sound in assistant professor Daniel Cuppoletti’s lab in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science. If flying cars are to succeed, Cuppoletti said, they'll have to be quiet.

UC aerospace engineering students Natalie Reed, Matthew Walker and Peter Sorensen presented papers with Cuppoletti at the Science and Technology Forum and Exposition this month in San Diego, California. Hosted by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, it’s the world’s largest aerospace engineering conference.

“I’m looking at noise from a societal impact,” Cuppoletti said. “These vehicles have to be imperceptible in the environment they fly in or someone will have to take the brunt of that impact.”

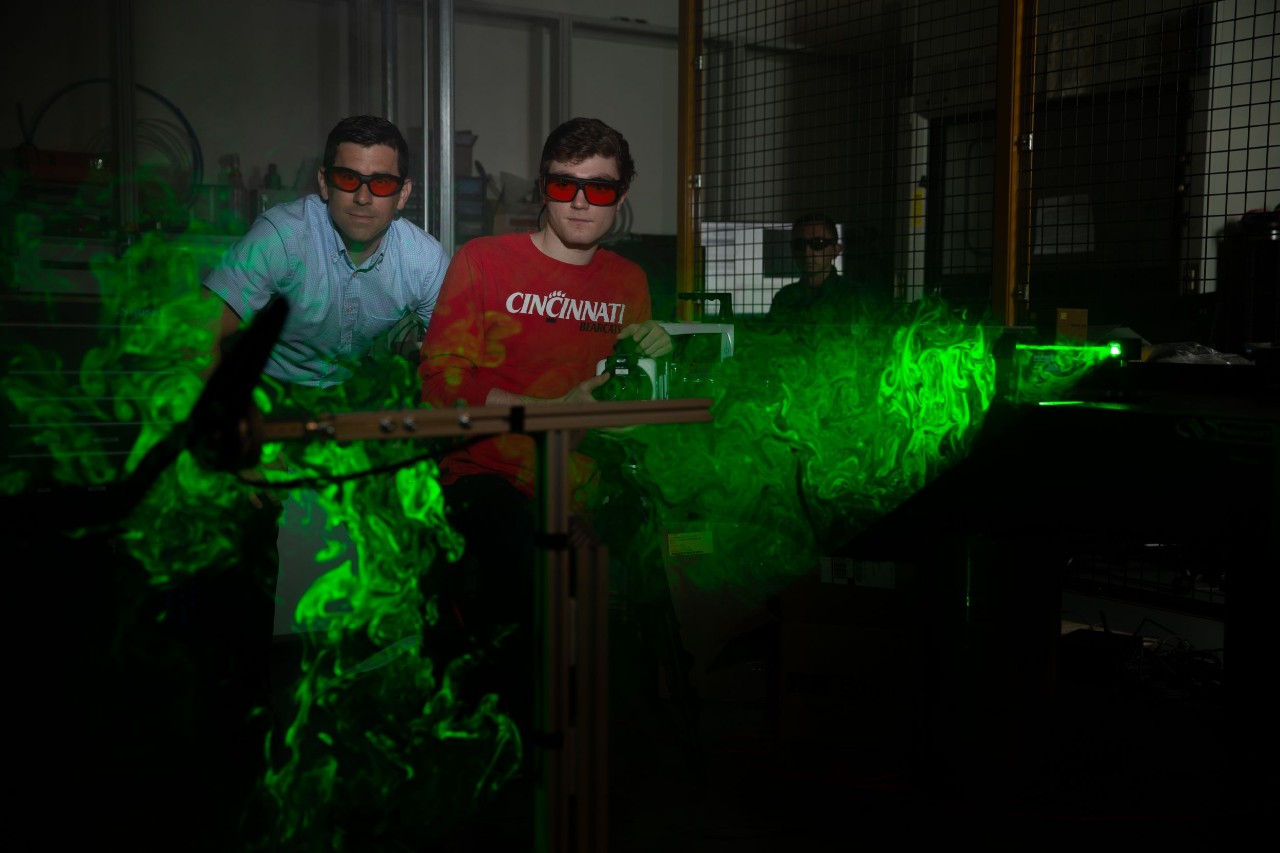

Aerospace engineering students in assistant professor Daniel Cuppoletti's lab use laser light to study the noise and flight characteristics of propellers at the UC College of Engineering and Applied Science. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Too often, the impact is felt in lower-income neighborhoods, he said.

Airports across the country are the subject of tens of thousands of noise complaints per year filed by aggravated residents. In an FAA survey published last year, two-thirds of respondents said they were “highly annoyed” by aircraft noise. Noise from planes and helicopters were a far bigger annoyance than cars, trucks or neighbors, the survey found.

Likewise, engine noise is a huge concern of the military and commercial aviation. Hearing loss and tinnitus are the leading causes of medical disability claims filed with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Drones don’t pose the same risk for hearing loss as bigger aircraft because they’re not much louder than a kitchen appliance. But the unique quality of their buzzing rotors stands out against the ambient background, which makes them irritating and distracting.

“One helicopter flying over your roof will keep you up,” Cuppoletti said. “If you want 1,000 drones flying over cities in urban centers, noise will be a huge problem.”

This is a very exciting time for aerospace.

Daniel Cuppoletti, Assistant Professor in UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science

A potential aggravating factor is sheer scale. While the United States sees about 5,700 commercial aircraft flights each day, drones with their diverse applications have the potential for thousands of flights in major metropolitan areas each day.

Cuppoletti said a variety of factors affect the way people perceive sound. Aircraft noise is far less noticeable in congested cities than suburbs or countrysides. And the time of day matters as well. Evenings tend to be quieter, making aircraft more noticeable.

“Studies have found that just seeing an aircraft can cause people to think they’re loud,” Cuppoletti siad. “There are subjective human factors you can’t control.”

Drones are being used in more commercial and public applications each year. UC aerospace students are studying ways to make them quieter. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Cuppoletti is studying how to manipulate sound from drones through engineering design. He tests sound in a room lined with sound-absorbing padding that eliminates echo.

Using an anechoic chamber, a room covered on all sides by sound-dampening material and outfitted with a suite of eight microphones, Cuppoletti tests the frequency, wavelength and amplitude of sound, among other factors that affect our perception of noise. He and his students are developing a guidebook that manufacturers of drones and flying cars can use to anticipate what their novel designs will sound like based on UC’s engineering and physics experiments.

Every rotor has its own noise signature. Simply by changing the configuration of two rotors can add or reduce sound by 10 decibels or more, UC student Reed said.

She tested 16 rotor configurations for the paper she presented at the SciTech conference.

“Changing the vertical gap influences the noise. So I looked at what happens if we change the vertical or horizontal spacing,” she said.

UC student Sorensen studied differences in sound in rotors rotating in the same direction versus opposite directions: co-rotating or counter-rotating. So far, the results are inconclusive.

With flying cars taking wildly imaginative forms on the drawing board, UC engineers hope to help create quieter designs.

“This is a very exciting time for aerospace,” Cuppoletti said. “New aircraft designs are at the preliminary and conceptual design stages. We can influence what they will sound like based on decisions designers make now.”

UC’s sound experiments will help manufacturers make more informed design decisions, he said.

Featured image at top: UC aerospace engineering professor Daniel Cuppolettie holds a scale-model propeller in a padded chamber that minimizes echoes. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Daniel Cuppoletti, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering in UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science, is studying ways to reduce the noise of flying cars and drones. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's medical, graduate and undergraduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

CCM Composition Professor awarded 2025 Guggenheim Fellowship

April 22, 2025

UC College-Conservatory of Music Composition Professor Mara Helmuth is appointed to the 100th class of Guggenheim Fellows, including 198 distinguished individuals working across 53 disciplines.

UC student over the moon about NASA co-op

April 22, 2025

When he graduates from UC’s School of Information Technology in May 2025, Colin Malott will have three years of interning with NASA to put on his resume. Malott was awarded a Scholarship for Service through the government agency whose leadership says he has all of the qualities that make a model intern.

Engineering doctoral student studying cyberattack prevention...

April 21, 2025

As a top graduating student in his undergraduate class, Logan Reichling came to the University of Cincinnati to further his education through the direct-PhD program in computer science. His initial connection to UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science was through his current advisor, Boyang Wang, in an undergraduate research program. Since arriving at CEAS, Reichling has been honored with several awards, including being named Graduate Student Engineer of the Month.