Conversion process turns pollution into cash

Converting carbon dioxide to ethylene holds commercial promise, professor says

Engineers at the University of Cincinnati have developed a promising electrochemical system to convert emissions from chemical and power plants into useful products while addressing climate change.

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science assistant professor Jingjie Wu and his students used a two-step cascade reaction to convert carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide and then into ethylene, a chemical used in everything from food packaging to tires.

“The world is in a transition to a low-carbon economy. Carbon dioxide is primarily emitted from energy and chemical industries. We convert carbon dioxide into ethylene to reduce the carbon footprint.” Wu said. “The research idea is inspired by the basic principle of the plug flow reactor. We borrowed the reactor design principle in our segmented electrodes design for the two-stage conversion.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Catalysis in collaboration with the University of California Berkeley and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

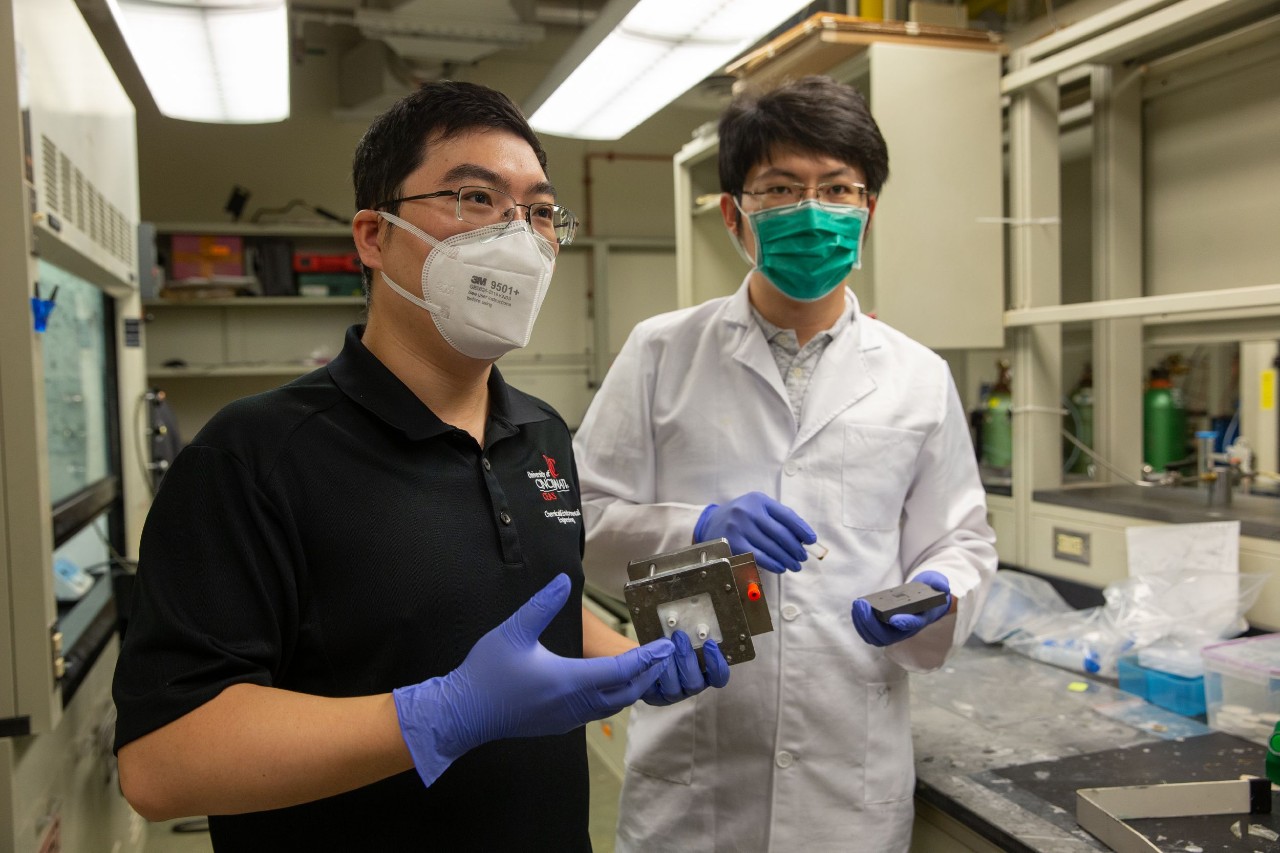

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science assistant professor Jingjie Wu, left, and UC graduate Tianyu Zhang are studying ways to convert carbon dioxide to useful products to address climate change. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science graduate Tianyu Zhang, one of the study’s lead authors, led a similar study last year that examined ways to convert carbon dioxide into methane that could be used as rocket fuel for Martian exploration.

“The significance of the two-stage conversion is that we can increase the ethylene selectivity and productivity at the same time with the low-cost strategy,” Zhang said. “This process can be applied to various reactions because the electrode structure is general and simple.”

Selectivity means isolating the desired compounds. Productivity is the amount of ethylene the reactor can produce.

“We’re selectively reducing carbon emissions into something considered valuable because of its many downstream applications,” Zhang said.

In the next 10 years, I’m optimistic we’ll see similar advances. This is a game changer.

Tianyu Zhang, UC College of Engineering and Applied Science graduate

Applications include a variety of industries from steel and cement plants to the oil and gas industry, he said.

“In the future, we can use this technique to reduce carbon emissions and make a profit from it. So, reducing carbon emissions will not be a costly process anymore,” he said.

Ethylene has been called “the world’s most important chemical.” It’s used in a range of plastics from water bottles to PVC pipe, textiles and rubber found in tires and insulation.

Professor Wu said the chemical they produce is known as “green ethylene,” because it is created from renewable sources.

“Ideally we can remove greenhouse gas from the environment while simultaneously making fuels and chemicals,” Wu said. “Power plants and ethylene plants emit a lot of carbon dioxide. Our goal is to capture the carbon dioxide and convert it to ethylene using electrochemical conversion.”

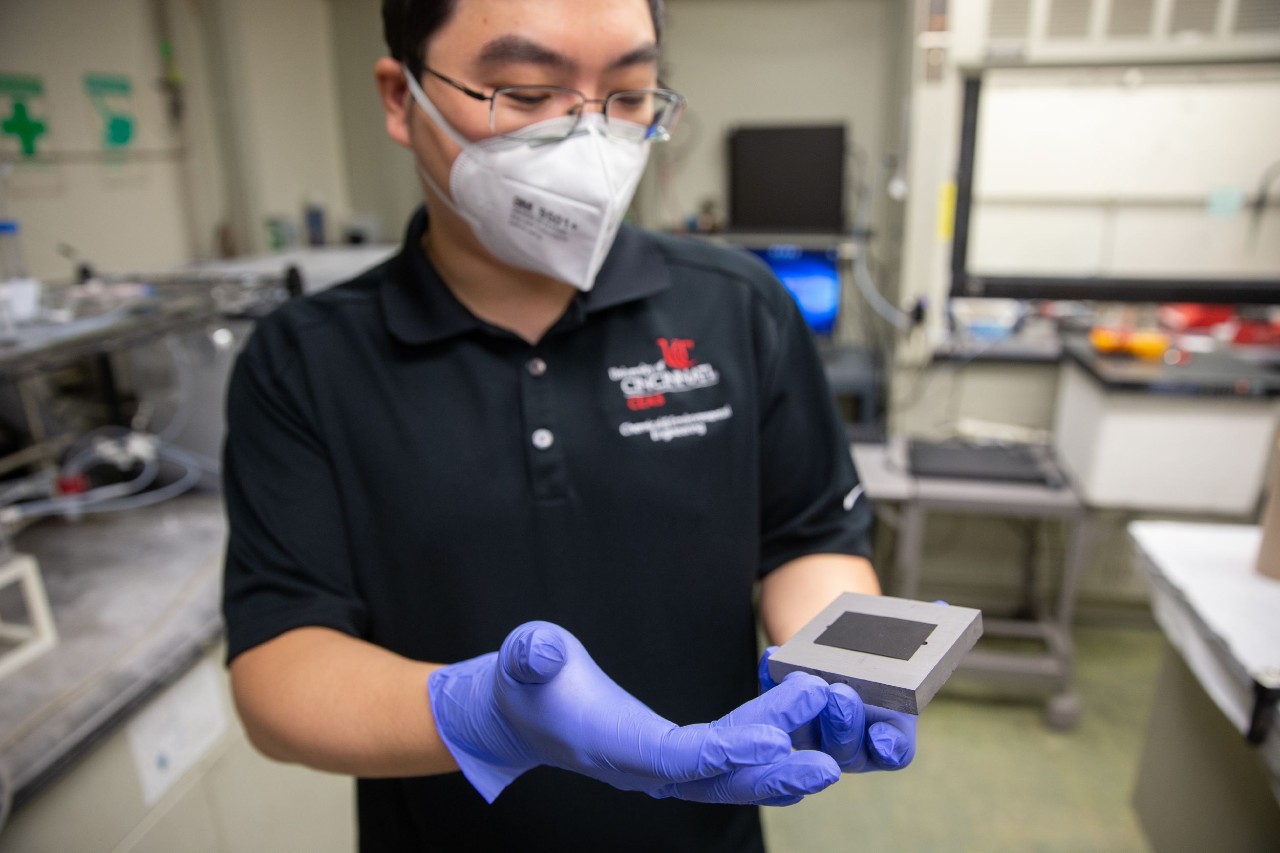

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science assistant professor Jingjie Wu is studying ways to convert carbon dioxide into useful products. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

So far, the process requires more energy than it produces in ethylene. By using tandem electrodes, UC engineers were able to boost productivity and selectivity, both of which are key indicators toward making the process commercially attractive to industry, Wu said.

There are huge environmental advantages to containing and converting greenhouse gases, Wu said.

“It’s being pushed by the government. In the future, we’ll need sustainable development so we’ll need to convert carbon dioxide,” he said.

And Wu said copper isn’t necessarily the best catalyst for this reaction, so industry experts have likely alternatives that could boost productivity and efficiency even more.

“Our system is very general, but you can use preferred catalysts,” Wu said. “But even with commercial copper we were able to more than double the performance. With an even better catalyst, we could solve the economic issue.”

Wu last year applied for patents for their design.

Zhang said the system will take some time to become economical. But already they have made tremendous strides, he said.

“The technology has improved a lot in 10 years. So in the next 10 years, I’m optimistic we’ll see similar advances. This is a game changer,” Zhang said.

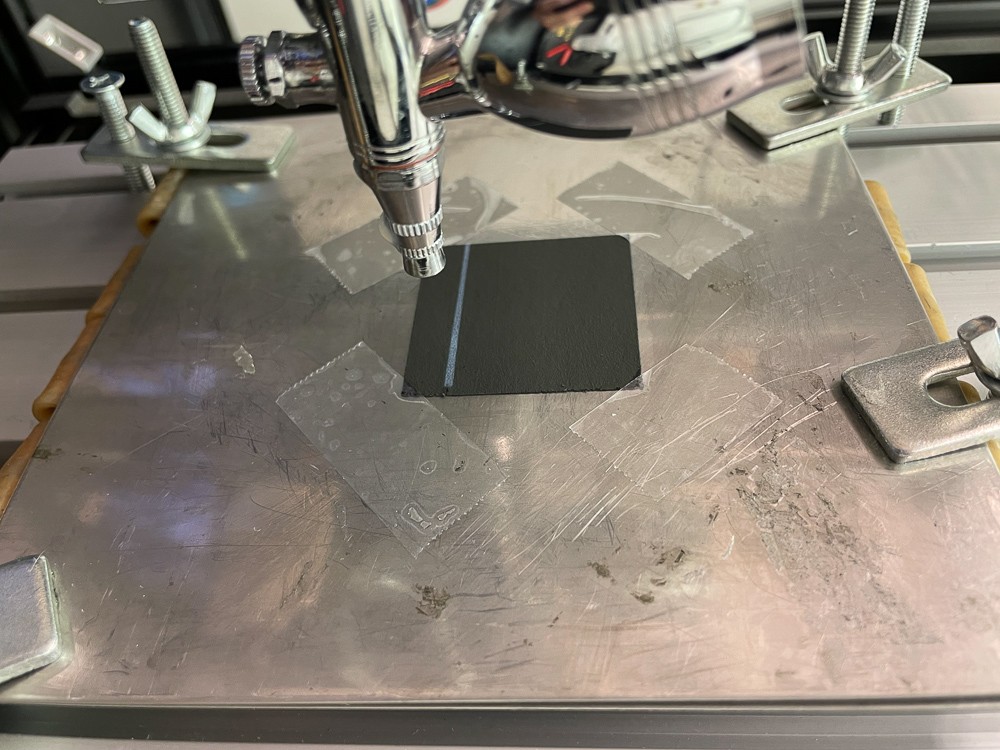

Featured image at top: UC chemical engineers are developing new processes to convert carbon dioxide into useful products using tandem electrodes. Photo/Jingjie Wu

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

PHOTOS: Welcoming spring with a festival of colors

April 15, 2025

UC’s campus was awash in color for an annual festival celebrating the start of spring. Students celebrated the holiday of Holi, which includes throwing colorful powders, painting revelers in a rainbow of hues. UC student photographer Kallista Edwards captured the technicolor festivities.

Paralyzed Veterans of America grant funds UC research with end...

April 15, 2025

University of Cincinnati researchers, in collaboration with end users in the community, have received a $200,000 grant from Paralyzed Veterans of America to design a user-centered, easy-to-use assistive device to help restore hand grasping motions for people with spinal cord injuries/diseases.

UC program tackles health care worker shortage

April 15, 2025

The Healthcare Exploration Through Patient Care course allows University of Cincinnati students to train and work as patient care assistants (PCAs) within the UC Health system, offering them paid, hands-on experience in hospital settings while earning academic credit.