Understanding racial health disparities

UC study examines biological reasons for increased dementia in Black population

When raising children, one approach does not fit all. Even though siblings may physically look similar, parents typically need to adjust how they discipline or reward children based on what they respond to.

In the same way, patients with the same disease that looks similar can respond to treatments differently depending on biological differences. Hyacinth I. Hyacinth, PhD, MBBS, said that as the medical field continues to identify and address systemic issues that lead to racial health disparities, it is also important to acknowledge and identify these biological differences across racial groups.

Hyacinth said he was drawn to researching conditions like stroke, cognitive impairment and dementia when he saw that these diseases significantly affect more patients of African ancestry compared to patients of European ancestry. His focus is to see how understanding biological differences can help reduce disparities.

“Obviously, we are all of the human race, but there are underlying differences in our genetic architecture and thus the proteins that result from these genetic architectural differences,” said Hyacinth, associate professor of neurology and rehabilitation medicine and the Whitaker and Price Chair in Brain Health in UC’s College of Medicine. “We should harness such signs of diversity, even at the [genetic] level, and use that to guide our development of therapy and even preventative strategies. If you develop a drug that takes into account these basic biological differences, a larger segment of the population will benefit.”

Hyacinth is currently leading a study seeking to determine how biological differences among racial groups contribute to higher rates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias among non-Hispanic Black compared with non-Hispanic white patients. Dementia is more than twice as prevalent in non-Hispanic Black populations compared to non-Hispanic white populations in the United States, after controlling for known risk factors.

Hyacinth I. Hyacinth, MBBS, PhD. Photo/Andrew Higley/University of Cincinnati.

Small vessel disease impact

Part of the study will focus on cerebral small blood vessels that supply nutrients and oxygen to different parts of the brain.

Hyacinth said that the cerebral small blood vessels can develop disease that can result in “tiny strokes,” the deterioration of healthy neuron fibers (called white matter hyperintensity) and small amounts of bleeding in the brain (called cerebral microbleeds), but the symptoms usually are not severe enough in the acute stage to be identified clinically. Typically, cerebral small vessel diseases (CSVD) are identified through MRI scans.

The UC study will research whether there is a higher disease burden of CSVD in non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients by analyzing MRI scans from participants who developed stroke or TIA while enrolled in a parent study known as REGARDS. Hyacinth said this dataset of stroke patients is being used because otherwise healthy people do not typically have MRI scans to analyze.

“If it is true, the higher CSVD burden may be one reason why non-Hispanic Black patients are more likely to have cognitive impairment and dementia compared to non-Hispanic white patients,” Hyacinth said.

Dr. Hyacinth works in his laboratory. Photo/Andrew Higley/University of Cincinnati.

Genetic impact

Researchers will also study the correlation between two separate gene variants and CSVD. Both genes have previously been identified as contributors that increase a person’s risk for cognitive impairment and dementia.

The first gene being studied and two variants of the second gene are more commonly found in non-Hispanic Black patients, while another variant of the second gene is more prevalent in non-Hispanic white patients.

“We are asking whether the presence of these genetic variations has anything to do with the burden of these cerebral small vessel diseases that we see,” Hyacinth said. “Because then that could tell us that it is very likely that part of the reason we see this high burden in non-Hispanic Black patients may in part, be due to the higher prevalence of these gene variants.”

Once this analysis is complete, Hyacinth said the researchers will combine the two factors to understand how much of the racial disparity in cognitive impairment and dementia can be explained by the differences in CSVD burden and underlying genetic variations. Understanding how these factors contribute to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias can potentially lead to identification of new drug targets, he said.

“Usually the cerebral small vessel disease tends to result from hypertension and inflammation, both treatable conditions,” he said. “So if we are able to show that it is part of the problem, then maybe we could develop more targeted drugs that better control hypertension or inflammation and so address the development of cerebral small vessel disease, leading to reduction of racial disparity in cognitive impairment and dementia.”

By seeing some of these differences, we can actually provide health education that’s more ethnically and biologically relevant, because right now our science and health education approach doesn’t look like the population.

Hyacinth I. Hyacinth, MBBS, PhD

Study impact

Hyacinth said that this is currently one of the largest studies of CSVD proposed among Black patients to date.

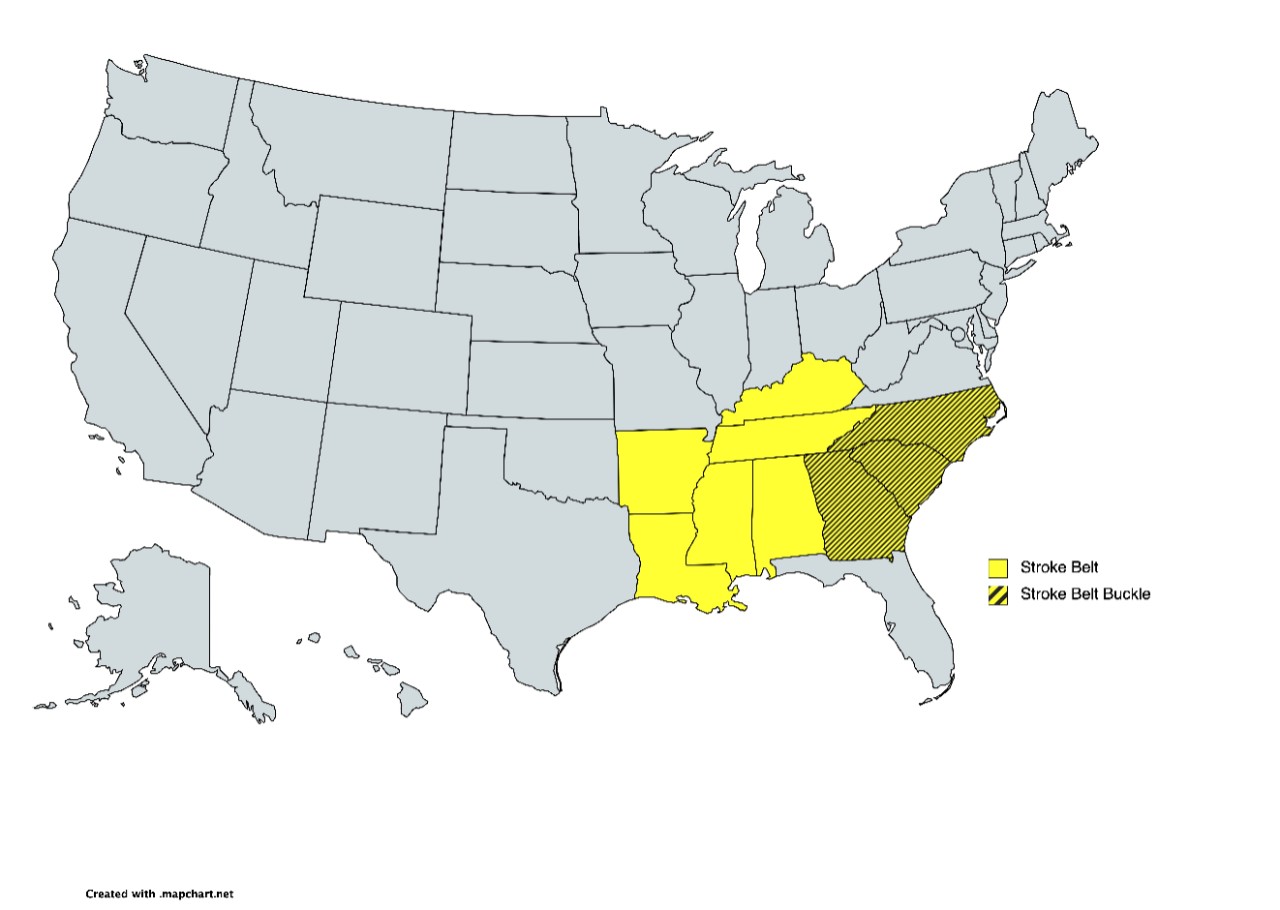

When completed, the study is also expected to help researchers learn about regional differences in CSVD burden, as well as other contributing factors, because the dataset being used includes about 28% of participants from the U.S. “stroke belt” and “buckle” of the stroke belt.

The stroke belt includes Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee (some add southern Virginia), with the buckle consisting of counties in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia having a higher incidence and mortality rate of stroke than anywhere else in the country.

“One exciting aspect of this study,” Hyacinth said, “is that for the first time, we will be able to examine the prevalence and burden of cerebral small vessel disease among participants in the stroke belt and compare with that of participants outside the stroke belt.”

Using data from the stroke belt and stroke belt buckle, Hyacinth said the research will help provide more insights on regional differences leading to cerebral small vessel disease, Alzheimer's and related dementias. Map created with mapchart.net.

If the difference between racial groups due to CSVD and genetics is quantified, Hyacinth said it could help guide how health care providers approach prevention efforts. By examining racial differences in risk at the biological level, health educators and providers could provide more specific and better tailored health education as well as treatment strategies.

“We talk about health care access issues, but maybe we need to re-tailor the way we provide health education, gearing health education to basically address group specific risk,” Hyacinth said. “If you think about it, when we provide education in our schools, we attempt to tailor it to the needs of our students. By seeing some of these differences, we can actually provide health education that’s more ethnically and biologically relevant, because right now our science and health education approach doesn’t look like the population.”

There is also potential that knowledge from the study could help encourage patients to take proactive steps to improve their health since CSVD is caused by treatable factors.

The research is funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, a division of the National Institutes of Health.

Featured photo at top of MRI brain scan. Photo/Ravenna Rutledge/University of Cincinnati.

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's medical, graduate and undergraduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Winter can bring increased risk of stroke

December 18, 2024

The University of Cincinnati's Lauren Menzies joined Fox 19's morning show to discuss risk factors for stroke in the winter and stroke signs to look for.

High-dose vitamin C shows promise in pancreatic cancer treatment

December 17, 2024

The University of Cincinnati Cancer Center's Olugbenga Olowokure was featured in a Local 12 story discussing new research from the University of Iowa that suggests that high doses of vitamin C, when combined with standard chemotherapy, may significantly extend the life expectancy of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

The American Prize recognizes CCM Composition Professor

December 17, 2024

UC College-Conservatory of Music congratulates CCM Distinguished Teaching Professor of Music Theory and Composition Miguel Roig-Francolí on his recent recognition from the American Prize.