UC members of NASA science team celebrate first year of Perseverance mission

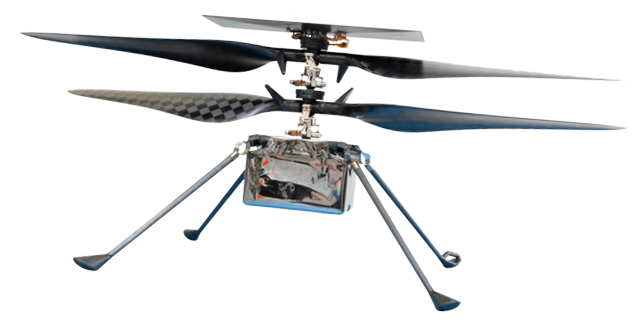

he first year of the Perseverance rover mission on Mars captured the imaginations of scientists and the public alike with an interplanetary helicopter flight and the first chance to hear the sounds of the red planet.

But two students at the University of Cincinnati say the best is yet to come in year two as the rover and their Perseverance science team begin in earnest to look for ancient life on another planet.

UC College of Arts and Sciences geology students Desirée Baker and Andrea Corpolongo are working on the NASA science team, using the rover and its helicopter sidekick, Ingenuity, to explore Jezero Crater near an ancient river delta that might hold clues of the first known extraterrestrial life.

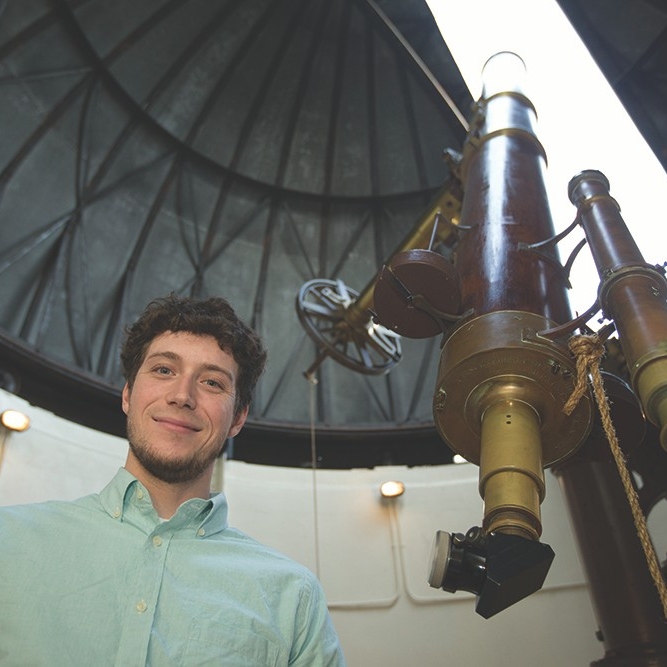

UC associate professor Andy Czaja served on the NASA advisory board that picked where to send the rover for the best chance to find evidence of ancient life. Now he and his two students are members of the mission science team helping NASA explore the red planet to answer fundamental questions about the origins of life in the universe.

One fundamental task of the mission: collect rock samples on the Martian surface to bring back to Earth during a future mission.

Czaja, who studies Precambrian paleobiology, astrobiology and biogeochemistry, is one of 16 scientists around the world named in June to a new NASA science group that will plan how the global scientific community will share and study those samples. The team includes experts in geology, geochemistry, planetary physics and epidemiology, among others.

“Mars is at the frontier of science. I’m excited and honored to be part of it,” Czaja said.

UC doctoral student Andrea Corpolongo, left, and associate professor Andy Czaja serve on the Mars 2020 team that is using the Perseverance rover to look for evidence of ancient life on the red planet. Here they pose with the telescope at the Cincinnati Observatory. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Strong spirit of exploration

Baker and Corpolongo work shifts as tactical documentarians, taking notes on daily decisions and their rationales to help the hundreds of other science team members stay informed and get back up to speed when they are not working. In particular, Baker documents decisions and discussions about an instrument called SHERLOC that uses cameras, spectrometers and a laser to search for signs of past microbial life on Mars.

“Each day on Mars is called a sol. For each day’s planning, we document what the pilot and scientists have in store for the next sol,” Baker said.

UC doctoral student Desirée Baker holds a rock containing fossilized mats of bacteria. As a member of the Mars 2020 science team, she is helping to look for similar evidence of ancient life on Mars. Photo/provided

The science team has a strong spirit of exploration, she said.

“It’s mind-blowing to think about,” she said. “You’re exploring another planet, looking at things never before seen until now and helping to interpret and share them.”

The rover conducts tasks in both daylight and darkness, so science team members work unusual hours during the Martian sol, which is 37 minutes longer than Earth’s 24-hour day.

Corpolongo also serves as a campaign implementation documentarian, which plans out the mission two days in advance of the tactical team.

That team will set up a plan for two sols in advance if everything goes perfectly,” Corpolongo said. “Then starting each tactical shift, you look at the previous campaign implementation documentarian report to get that high level picture of what’s going on today.”

Typically, the rover’s itinerary and objectives go as planned, but when there are surprises or challenges, the campaign implementation team adjusts accordingly, she said.

“I call it a science party. It is hard for me to put into words how cool it is to be part of this international mission with eyes all over the world on it,” Corpolongo said.

Helicopter sidekick

Baker said after its historical flights proved successful, the helicopter Ingenuity is serving as an advance scout for Perseverance, helping to identify potential pitfalls and intriguing rocks on its designated route.

UC doctoral student Andrea Corpolongo, left, and associate professor Andy Czaja serve on the Perseverance science team exploring Mars in search of evidence of ancient life. Photo/Andrew Czaja/UC Marketing + Brand

“That’s been an unexpected bonus for Ingenuity. Now we’re finding new ways to use it,” Baker said. “The rover has to be careful where it drives. It’s a desert environment with soft sand.”

Czaja said he doesn’t know if Perseverance will find evidence of ancient life on Mars. But he has confidence in the rover’s ability to look for it. And the location NASA selected for the search is promising, he said.

Jezero Crater lies next to what scientists believe to be an ancient river delta. On Earth, these are likely places to harbor evidence of ancient life since organic life would get swept downstream to this standing water where it quickly would get covered over and preserved in fine sediment.

“It looked like a river delta from orbit, but there are things you can’t see from orbit that we have now that demonstrate this was, in fact, a delta,” Czaja said.

'Seven minutes of terror'

If Perseverance does find what looks to be tangible evidence of ancient life, confirmation likely will have to wait until a return mission to retrieve the samples the rover collects. These analyses are bound to reveal other surprises back on Earth.

“That’s one of the great things about sample return. You’re not just doing it to answer the questions we have today,” Czaja said. “There may be questions nobody has even thought of yet. The person who thinks of that question might not have been born yet.”

Perseverance has celebrated a series of successes from its launch to its touchdown on Mars seven months later via a Skycrane, a rocket-powered descent vehicle that lowered the rover to the surface via cables. Before the launch, NASA engineers described the spacecraft’s final descent through the thin Martian atmosphere as “seven minutes of terror.”

Czaja and other members of the science team tuned in to the JPL livestream to watch as they learned of the spacecraft’s fate, deploying its parachute, jettisoning its heat shields and lowering the rover by cables onto the Martian surface.

“Watching the landing, I remember being too excited to sit down,” Czaja said. “My heart was in my throat. Suddenly, a picture shows up of the underside of the rover and its surroundings on Mars.”

Perseverance was ready to explore.

“There is a really big question if we find evidence of ancient life on Mars. Is it the same as ancient life on Earth? Did life on both planets have the same origins?” Corpolongo said. “There are so many questions.”

An artist's rendering of Perseverance dropping onto the surface of Mars via skycrane, a high-speed entry into the Martian atmosphere that researchers call "seven minutes of terror." Graphic/NASA-JPL-Caltech

In the first year of the mission, Czaja got a chance to name a geographic feature on Mars in accord with the naming conventions established for each mapped quadrant. NASA created a list of approved names associated with national parks around the world. One quadrant was associated with Verdon Natural Regional Park in France so Czaja named a ridge Mount Gourdan for a feature in the Alps.

“It’s been pretty exciting. When you’re working day to day, you lose sight of that a little bit. But when you step back, it makes you think, ‘This is really exciting,’” Czaja said.

Czaja said it’s been fun to contribute to the decision-making on the mission. Every choice has costs, risks and benefits that must be considered, he said.

“We’re a bunch of scientists so we like to argue the merits of our ideas,” he said. “There is so much we’d like to explore. You want to be as efficient as possible and meet all the goals of the mission in the time allotted.”

Many things can go wrong in a mission as complicated as this undertaking, so each day’s work is precious, presenting tantalizing scientific possibilities, Czaja said.

“You’ll never know if you stop looking. It might be around the next bend or over the next hill,” Czaja said.

More UC Ties to

Space

UC grad explores final frontier

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science 2022 graduate Anna Lanzillotta worked four co-op rotations at NASA.

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science graduate Anna Lanzillotta works for the Idaho National Laboratory where she is developing new nuclear-powered batteries for NASA. Photo/Corrie Mayer/UC CEAS Marketing

Lanzillotta, an electrical engineering grad, worked two co-ops at the Johnson Space Center in Houston as an audio systems engineer. In one project, she designed and tested solutions for the communications used in NASA’s next-generation spacesuits that astronauts will wear when they return to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

She also was accepted into the NASA Pathways Program, where she spent two co-op rotations at the Langley Research Center in Virginia. There she worked on spaceflight hardware before turning her attention to advanced applications for use aboard the International Space Station.

After graduating this spring, Lanzillotta accepted a position with the Idaho National Laboratory, where she will be working on nuclear-powered batteries for NASA for its upcoming drone mission to Titan, Saturn’s biggest moon.

Life beyond Earth?

UC College of Arts and Sciences graduate Kevin Wagner was named a Sagan Fellow in 2020 as part of NASA’s Hubble Fellowship Program.

UC graduate Kevin Wagner searches the universe for new planets. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Marketing & Brand

Wagner studied astrophysics at UC before earning a doctorate at the University of Arizona, where he received a National Science Foundation fellowship. In 2018, he was part of a team that imaged a newly forming planet using the Magellan Clay telescope in Chile.

Now he is looking for planets in close proximity to stars that might harbor life. Physicists call this the “habitable zone,” and it’s comparatively small.

“Finding a planet is one of the rarest and most-sought-after accomplishments, but it’s actually becoming slightly more common with dedicated telescopes looking for transiting planets,” Wagner said in a 2017 interview.

With the 2021 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers now have even more powerful tools at their disposal to pursue fundamental questions about the universe. And UC graduates such as Wagner will help answer those questions.

One small step

After setting foot on the moon and becoming one of the most famous people in the world, Neil Armstrong left NASA to teach aerospace engineering in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science.

UC professor Neil Armstrong folds a paper airplane during a student exercise about flight characteristics. Armstrong served as a test pilot before and after his famous moonwalk. Photo/UC Marketing & Brand

Armstrong, a native of Wapakoneta, Ohio, blasted off from Cape Canaveral with fellow astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins during the Apollo 11 mission, making the universe a little smaller when he set foot onto its chalky surface with his famous, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The successful mission sealed Armstrong’s place in history. But Armstrong wasn’t satisfied with being a historical footnote. He taught a generation of aerospace engineering students at UC until his retirement in 1979. At UC, Armstrong inspired countless engineers to pursue their aviation and aerospace dreams.

“Neil viewed himself as just an ordinary person,” engineering professor emeritus Ron Huston said in a 2012 interview. “He fully understood that the moon landing was the result of long, hard work of many people. Neil did not want to leave the impression that he did it all on his own.”

Reaching the Moon

UC physics alumnus George Sherard Jr. never made it to the moon, but neither would the crew of Apollo 11 without his help.

George Sherard. Photo/Provided

Sherard was one of many African Americans who played a crucial but unheralded role in the space program. He worked on Apollo 11’s guidance and navigation systems as a contractor for Rockwell International, where he trained astronauts on how to respond to every conceivable mission failure in simulations.

At UC, Sherard earned a bachelor’s degree in physics in 1940 with honors as a special scholar and a master’s degree while pursuing a doctorate at the start of World War II. He followed his passion for aviation to Rockwell, where he worked on all six successful Apollo missions to the moon.

“We worked around the clock without a thought of going home and getting rest. We’d eat in the cafeteria, brush our teeth in the bathroom and carry on,” Sherard said in a 2000 interview. Sherard died in 2003.

After the Apollo missions, Sherard returned to Cincinnati where he worked at General Electric Aviation. He married his former UC classmate, Emma Sherard.

The 'worm' returns

Internationally renowned graphic designer Bruce Blackburn graduated in 1961 from UC’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning before spending his career crafting graphic images for brands, government and nonprofits.

Technicians affix a NASA decal to a SpaceX rocket. UC College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning graduate Bruce Blackburn designed the logo for NASA in 1973. NASA brought it back in 2020 for its latest SpaceX missions. Photo/Cory Huston/NASA

Blackburn designed the recognizable blue logo for Absolut vodka and the stitchwork red, white blue star logo for the American Revolution Bicentennial.

But he is perhaps best known for the iconic NASA logo known as “the worm.” With its futuristic custom inchworm-like red font, the logo was the public face of NASA for more than 17 years. President Reagan bestowed a Presidential Design Award on Blackburn in 1984.

Blackburn worked with clients such as IBM, Prudential and Mobil. He died in 2021. Blackburn told the New York Times that the NASA and Revolutionary War logos were among his biggest feats. NASA brought back his iconic logo in 2020 for its latest SpaceX missions.

“They say in life there are moments that are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities,” Blackburn said. “And I got two of them."

Related Stories

UC celebrates record spring class of 2025

May 2, 2025

UC recognized a record spring class of 2025 at commencement at Fifth Third Arena.

UC students recognized as outstanding peer career coaches

May 1, 2025

Two University of Cincinnati students are recognized for outstanding contributions to the Bearcat Promise Career Studio in the 2024-2025 academic year.

UC students recognized for achievement in real-world learning

May 1, 2025

Three undergraduate University of Cincinnati Arts and Sciences students are honored for outstanding achievement in cooperative education at the close of the 2024-2025 school year.

CCM welcomes new viola faculty member Brian Hong

May 1, 2025

UC College-Conservatory of Music Dean Pete Jutras has announced the appointment of Brian Hong as CCM's new Assistant Professor of Viola. His faculty appointment officially begins on Aug. 15, 2025. Hong has established a notable career as a critically acclaimed performer, inspiring pedagogue and successful music administrator. As the violist of the GRAMMY-nominated Aizuri Quartet from 2023-2025, he premiered major new works on nationally renowned chamber music series and conducted residencies at universities across the United States.

‘Doing Good Together’ course gains recognition

May 1, 2025

New honors course, titled “Doing Good Together,” teaches students about philanthropy with a class project that distributes real funds to UC-affiliated nonprofits. Course sparked UC’s membership in national consortium, Philanthropy Lab.

DAAPworks reveals 2025 Innovation Awards – discover the winning...

May 1, 2025

Visionary projects stole the show during DAAPworks 2025, from wayfinding technology for backcountry skiers to easy-to-use CPR training kits for children.