UC chemists, geologists, art historians collaborate with museums to examine masterpieces

orgeries are a lucrative global market created by artists so skilled in both their craft and their duplicity that they sometimes fool even the experts.

But curators at the Taft Museum of Art are using scientific tools more commonly associated with geology and chemistry to answer questions about masterpieces that have perplexed generations of art historians.

The museum invited researchers and art historians from the University of Cincinnati to their conservation lab to deploy X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy on two beautiful but suspect paintings in its collection.

The Taft Museum of Art’s curators and other scholars have traced the origins of nearly all of the museum’s nearly 800 works, including paintings, decorative art and furniture. Their meticulous work since opening in 1932 has called into question the authenticity of a few pieces the museum has kept off exhibit — until now.

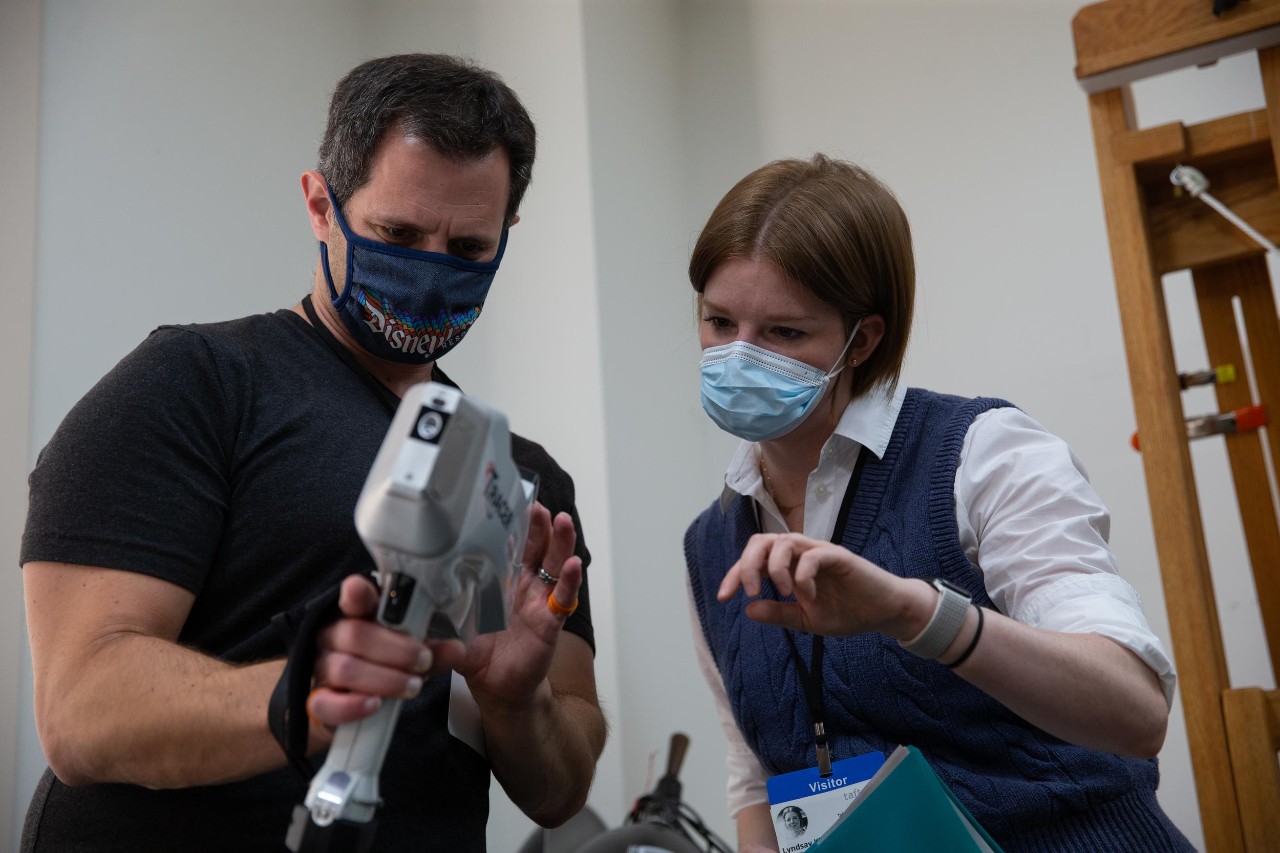

UC geologist Daniel Sturmer uses Raman spectroscopy to learn more about a painting titled Crucifixion at the Taft Museum of Art. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Taft opened an exhibition titled “Fakes, Forgeries, and Followers in the Taft Collection” that runs through Feb. 5 showcasing paintings, decorative arts and furniture previously attributed to artists such as Dutch master Rembrandt and Spanish artist Goya. Some of these pieces have not been displayed in nearly 30 years, including two paintings UC’s researchers examined.

The first, titled “Panel with the Crucifixion,” is a depiction of the Crucifixion, one of the most iconic stories in Christianity, on a gold background on a decorative wood panel. It is in the style of early Italian Renaissance artist Bernardo Daddi who painted similar scenes of the Crucifixion and other religious iconography in the 13th century.

Museum curator Tamera Lenz Muente said experts have questioned the authenticity of the piece. In the 1995 catalogue of the Taft Museum of Art’s European and American Paintings, the late art historian Rona Goffen was skeptical of the painting’s creator.

To learn more, the museum turned to an interdisciplinary team of researchers in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences and College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning.

If you go

The Taft Museum of Art’s new exhibition Fakes, Forgeries, and Followers in the Taft Collection runs now through Feb. 5. The exhibition will showcase some pieces that have not been displayed in 30 years.

UC assistant professor of chemistry Pietro Strobbia, his postdoctoral chemistry researcher Lyndsay Kissell, assistant professor of geosciences Daniel Sturmer and UC art historian and assistant professor Christopher Platts brought some of the same powerful tools NASA uses on the Mars rover Perseverance in its search for evidence of ancient life.

“Raman spectroscopy is a very powerful tool for this work,” Strobbia said. “You won’t find certain elements in old pigments. It’s an easy way to date the pigments in a painting.”

A Tang Dynasty dancing horse at the Cincinnati Art Museum/Gift of Carl and Eleanor Strauss, 1997. Photo/Cincinnati Art Museum

But chemical analysis can reveal surprising details about even authentic works, he said.

“It can tell you the intended audience a painting was made for,” Strobbia said. “If the pigments were expensive, you might tell that it was commissioned for someone wealthy, not the general public.”

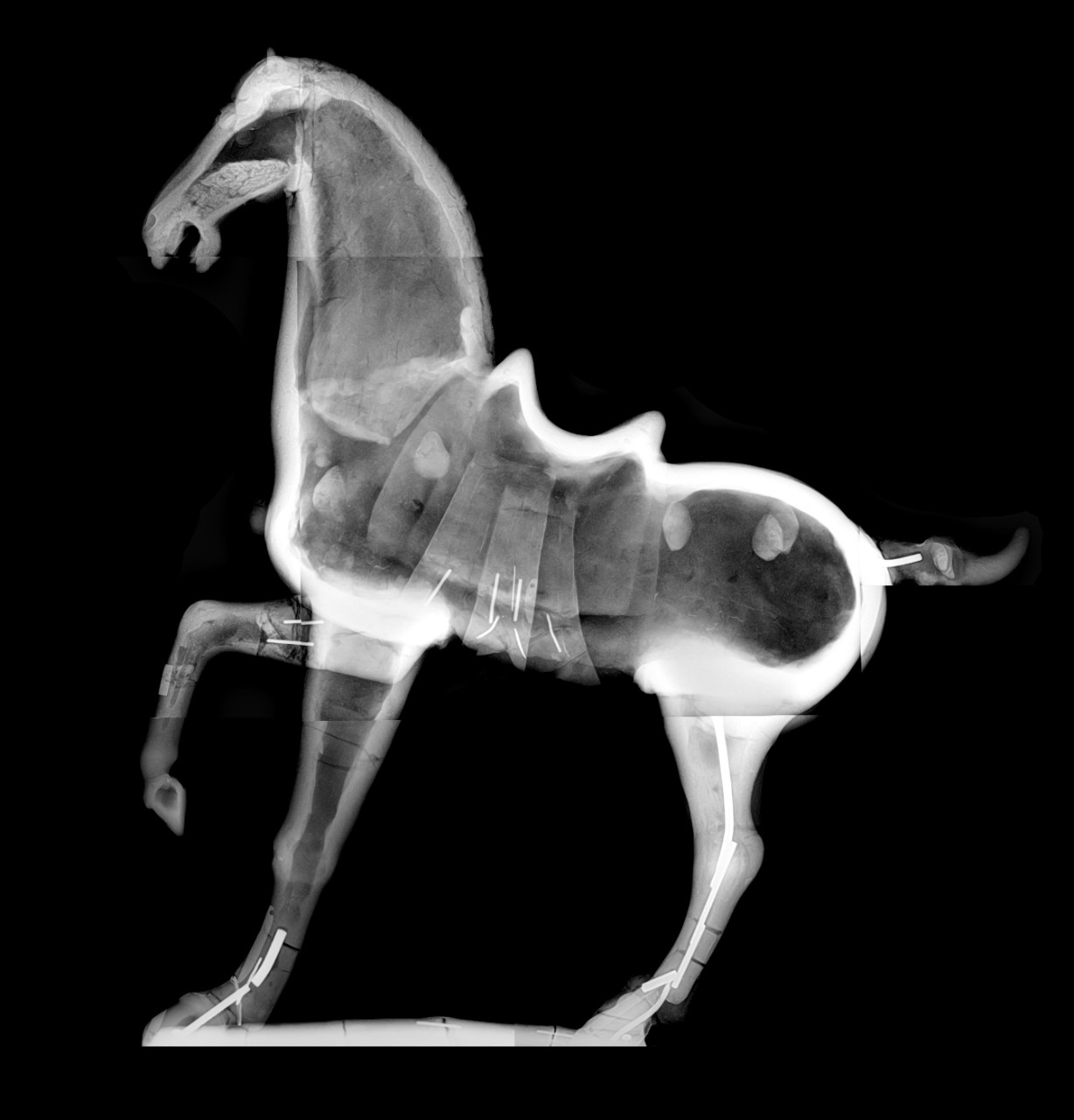

Strobbia and colleagues at Italy’s Institute of Heritage Science, recently helped the Cincinnati Art Museum determine if portions of a restored 1,300-year-old Chinese dancing horse sculpture were original to the work. Strobbia’s chemical analysis determined that a tassel on the ancient sculpture’s forehead was made from a different material than the rest of the terra cotta horse.

Platts has an enduring fascination with the history of art forgery. Forgeries sometimes are made explicitly to fool buyers. Other times, artists are merely inspired by the greats, he said.

“Artists will sometimes emulate those they admire and do so in such a convincing way that it’s hard to tell their works apart,” he said. “The way artists learn is by duplicating others’ work.

“So we often try to use more conditional language,” Platts said.

Chemical analysis revealed modern pigments in the painting, museum curator Muente said.

“Zinc white was not available during the Italian Renaissance,” she said. “Finding that would be a giveaway.”

But it’s still unknown whether the painting represents an intentional forgery or merely an imitation, she said.

“We don’t know for sure if there was intent to deceive on the part of the artist or the dealer,” she said. “There are many layers to these stories. Using both science and scholarship to reveal the true origins of a work of art is fascinating but still leaves some questions.”

For example, the wooden panel appears to be centuries older than the pigments used in the painting.

“It’s possible that someone trying to create a convincing forgery would get their hands on a centuries-old wooden panel and add their painting on top of it,” she said.

Platts said the history of forgery is steeped in the psychology of ego and hubris.

“Some artists want to fool people out of a sense of wounded pride and spite for the people who hurt them,” he said.

UC assistant professor of geology Daniel Sturmer consults with UC postdoctoral chemistry researcher Lyndsay Kissell on the team's chemical analysis of pigments in a painting. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Next, the researchers turned to a more recent work titled “Landscape with Canal,” circa 1820-1860, once thought to be by English landscape painter John Constable whose signature adorns it. It depicts a pastoral scene of a farm reflected in the placid water of a canal. There are sleepy horses, heads drooped, and passengers embarking on a boat down the canal near two other boats docked in a corner next to some grazing cows.

Art historians said the painting is very much in the manner of Constable’s works. But experts have said the artist more likely was Frederick Waters Watts, whose work follows the landscape master.

“Constable is one of the most famous landscape artists of 19th century England,” Platts said.

“The composition and the space of this picture as well as the subject and atmosphere are highly ‘Constablesque,’” experts wrote in The Taft Museum: European and American Paintings. “The romantic longing for the security of an imagined past, the fresh breeze of the natural world and the confrontation with the modern ways are brought harmoniously together.”

UC assistant professor of art history

Platts said the clouds that dominate the piece are inconsistent with those in other Constable works. The signature was partially covered in some of the painting’s brush strokes, suggesting the artist had signed it and then made some later final touches to the masterpiece.

But Platts said the yellow paint strokes over the signature are a red flag.

“It was almost as if they were trying too hard,” he said. “Why would you paint over the signature?”

So who added the Constable signature?

UC’s examination was inconclusive. Muente said researchers could learn more by taking a paint sample at the signature and examining its layers under a microscope.

“You embed it in resin and shave it down to get a cross section. Then you can see the stratification of the layers of paint,” she said.

Muente said experts agree it’s not a Constable.

UC researchers collaborated with experts at the Taft Museum of Art to answer questions about two paintings. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

If the painting is by Watts, Platts said, it is more likely that an unscrupulous seller rather than Watts perpetrated the fraud by adding a phony signature. Muente said Watts exhibited his paintings widely under his own signature and deeply admired Constable’s work.

“While Watts spent his career painting like Constable,” Platts said, “for collectors, a signed Constable would be more valuable.”

UC researchers are excited about their collaborations with the area’s museums. And they think there could be more demand for scientific analysis of the region’s artworks.

“The Taft Museum of Art is telling new stories about these works that the public has never seen before,” Platts said.

While many of the region’s art museums have conservators dedicated to cleaning or restoring these treasures, few are able to analyze them in this degree of scientific detail. That’s where UC could come in, he said.

UC geologist Daniel Sturmer, center, uses an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer to study the elements found in the pigments of a painting in UC's art collection. Also pictured are UC art historian Christopher Platts, left, and Aaron Cowan, director of UC's art collection. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Showing students the science

Platts and Strobbia want to create a new interdisciplinary honors course for students interested in both science and art where they would draw from their expertise in chemistry, geology and art history to learn more about the history of art, including UC’s large collection on display in buildings across UC’s campuses.

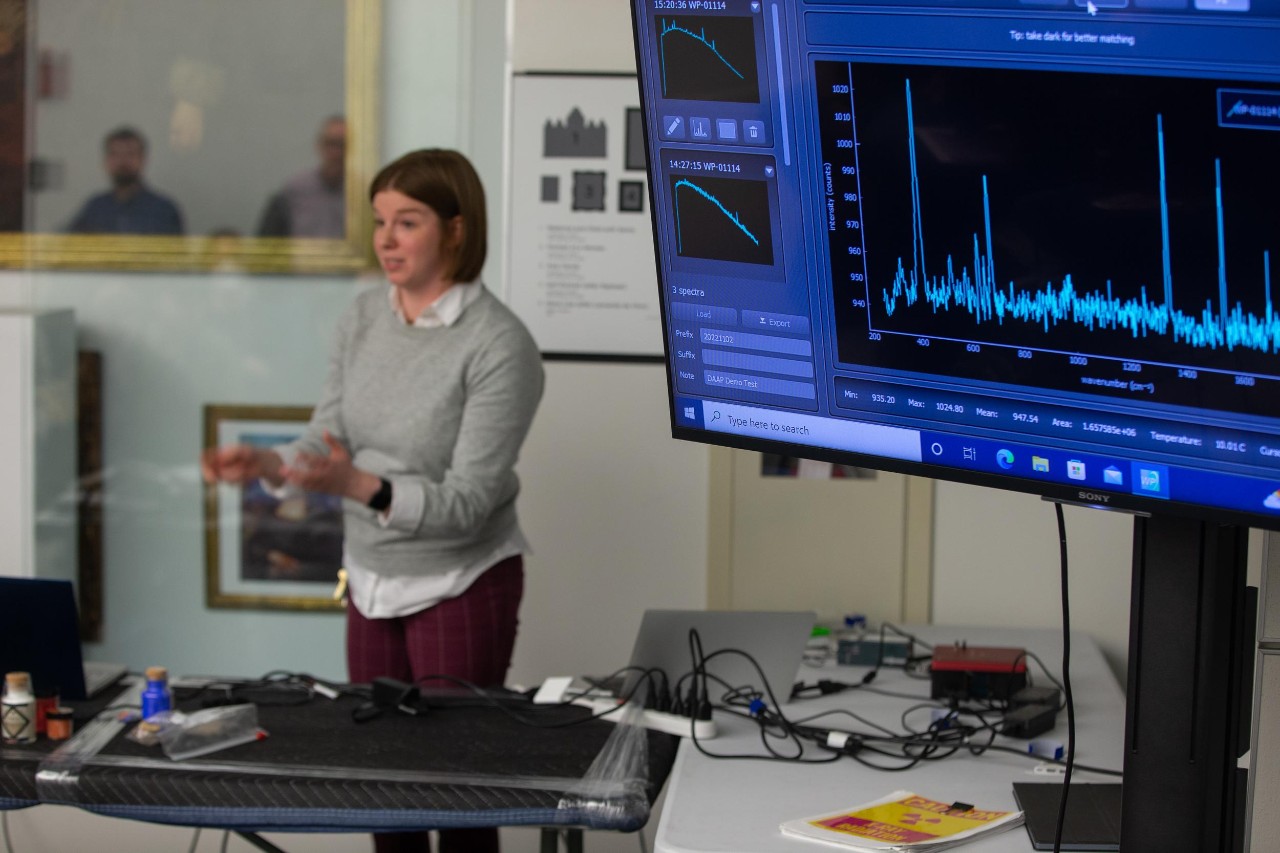

UC chemistry postdoctoral researcher Lyndsay Kissel gives a demonstration to UC art history students of scientific tools they can use to detect art fakes and forgeries. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

“What a fascinating class that would be,” Muente said. “It represents great cross-disciplinary work.”

Inspired by his collaboration with the Taft Museum of Art, Platts has enlisted the help of his College of Arts and Sciences research partners to give a scientific demonstration to his art history students in November on selected pieces of Italian Renaissance or European Baroque art from UC’s collection.

Chemists and geologists used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to examine the pigments in one portrait for clues on when it was painted. The technique can also provide clues about the quality of the pigments or materials used, informing historians about both the artist and the person who commissioned the work, Platts said.

Likewise, he said, some older pigments are toxic and would not be used today.

“But meticulous forgeries would strive to use pigments from the time,” Platts said.

Students said they were impressed by what chemistry and geology can add to a historical examination.

“The technology is completely new to me. It's amazing what we can learn from a scientific examination,” UC art history major Russell McCabe said.

UC art historian Christopher Platts, an assistant professor in UC's College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning, tells his students how pigments can be dated by the elements they contain. Also pictured is UC postdoctoral researcher of chemistry Lyndsay Kissell. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

UC's art-science collaboration in the news

An X-ray of a Tang Dynasty dancing horse at the Cincinnati Art Museum/Gift of Carl and Eleanor Strauss, 1997. Image/Cincinnati Art Museum

- Smithsonian: Chemistry reveals history of ancient horse sculpture

- Washington Post: Art meets science in analysis of dancing horse statue

- ZME Science: Cutting-edge analysis reveals modern additions to historic dancing horse statue at Cincinnati Art Museum

- Lab Manager: Using science to solve 1,300-year-old mystery

Featured image at top: University of Cincinnati experts used scientific tools to examine a painting in the Taft Museum of Art's collection titled Panel with the Crucifixion, from an imitator of Bernardo Daddi made in the late 1800s or early 1900s, possibly Florence, Italy, tempera and gold on canvas, a bequest of Jane Taft Ingalls in 1962.

Digital design/Kerry Overstake/UC Digital + User Experience

Become a Bearcat

Whether you’re a first-generation student or from a family of Bearcats, UC is proud to support you at every step along your journey. We want to make sure you succeed — and feel right at home.

Related Stories

UC‘s College of Arts and Sciences taps innovative new leadership

December 20, 2023

The College of Arts and Sciences announced Ryan J. White and Rina Williams as the newest divisional deans of Natural Sciences and Social Sciences. White and Kennedy’s inclusion will bring new focuses and structure around student success and the college of Arts and Sciences’ advancement. Both will officially begin their new terms on Jan. 1, 2024.

What is UC’s 4 + 1 program?

December 4, 2023

You may be a UC student thinking about taking your education to the next level — UC’s College of Arts and Sciences has a pathway to help you do just that. A&S has no fewer than 15 five-year programs — from biological sciences to Spanish to psychology — where you can earn both your bachelor’s and master’s degrees in just five years, versus the traditional six-year track. The Bachelors and Master’s 4 + 1 Program is designed to increase your marketability and deepen your understanding of the subject matter. And in an increasingly competitive job market, you may want to investigate an additional year of study.

Clifton Court Hall grand opening garners detailed media coverage

September 20, 2023

The University of Cincinnati celebrated the opening of Clifton Court Hall on Tuesday, Sept. 19, with a ribbon cutting, attended by approximately 200 administrators, faculty, staff and students. The event was covered by multiple media outlets.

UC offers new social justice, Latin American studies degrees

October 7, 2020

University of Cincinnati students can now enroll to earn a Bachelor’s degree in two new humanities programs: Social Justice, and Latin American, Caribbean and Latinx Studies, offered through UC’s College of Arts and Sciences.

UC: Spice up your spring courses next semester

November 5, 2024

As students forge ahead through the fall semester, Open Enrollment season quickly approaches. New and continuing students at the University of Cincinnati are able to login to Catalyst and enroll in spring semester courses beginning on November 25. The College of Arts & Sciences offers a wide range of unique courses that can help students fill a few extra credit hours while having fun in a memorable class.

UC to celebrate grand opening of Clifton Court Hall

Event: September 19, 2023 3:00 PM

The University of Cincinnati on Sept. 19 will celebrate the grand opening of Clifton Court Hall, the biggest classroom building on UC’s Uptown campus.