Ancient Maya faced bane of urban sprawl, too

New lidar maps reveal enormous city hidden under rainforest

The ancient Maya’s Calakmul once was the biggest city in the Americas, full of apartment complexes, temples and shrines stretching across an area the size of Washington, D.C.

New mapping tools are giving an international team of scientists their first complete look at the scale and complexity of the enormous metropolis hidden beneath centuries of rainforest growth in Campeche, Mexico.

“In a society like this, people are power. Being able to manage and concentrate people in a limited space, especially given technological limitations, required a lot of thought and planning,” said Nicholas Dunning, an archaeologist at the University of Cincinnati.

Dunning, a professor in the Department of Geography & Geographic Information Systems, led a contingent of UC experts in geography, anthropology and biology on a project sponsored by the National Science Foundation. UC’s researchers have been collaborating for years on studies of ancient civilizations in Mesoamerica and the American southwest.

UC is participating in the Bajo Laberinto archaeological project led by the University of Calgary, the Autonomous University of Campeche and the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

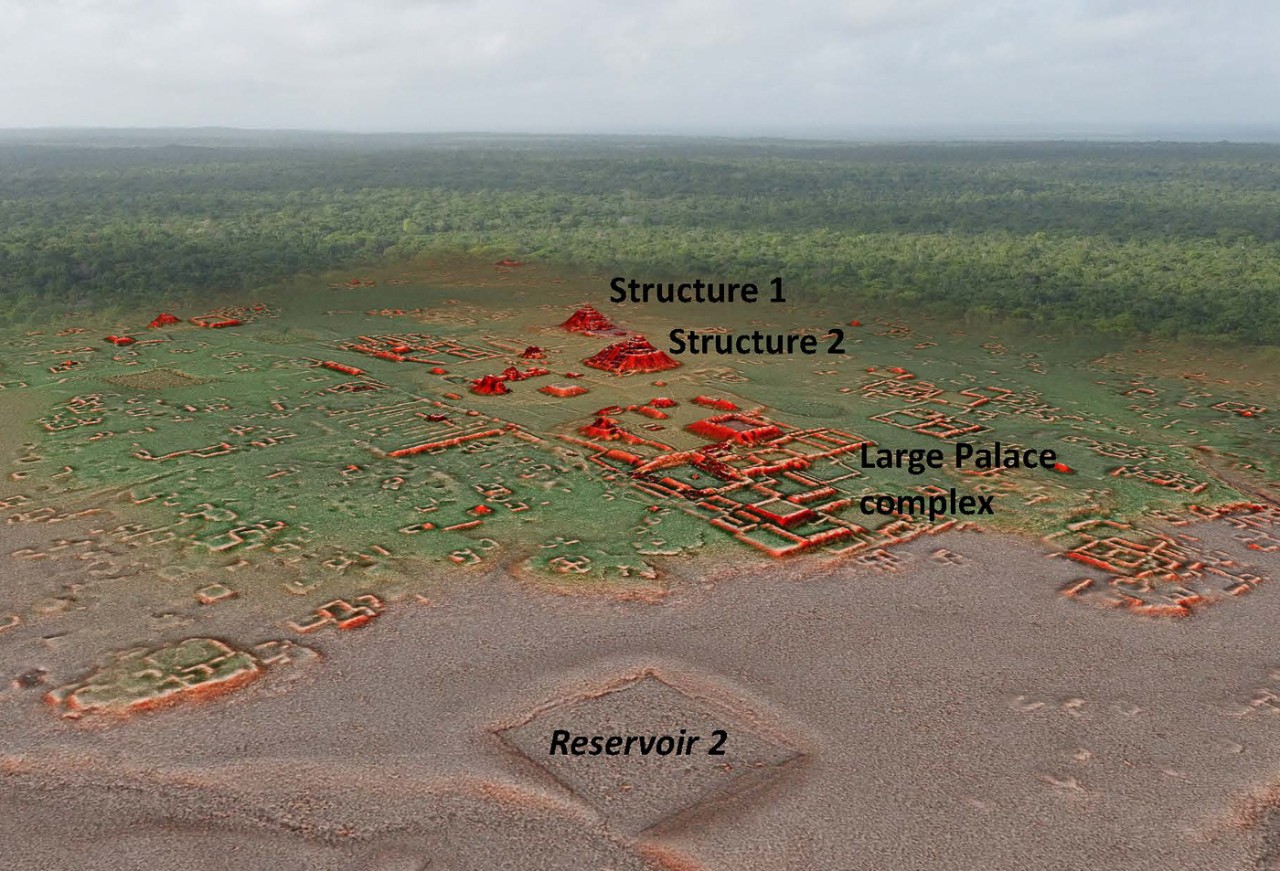

University of Cincinnati researchers relied on new lidar images like this one showing on overview of central Calakmul created by the Bajo Labertino Archaeological Project and Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Researchers used a tool called light detection and ranging (lidar) to scan the ground hidden beneath the thick rainforest. What they found was astonishing.

Lidar scans revealed the foundations of ancient palaces, multifamily homes, temples, shrines and marketplaces. Some of the family compounds contained 60 or more buildings for extended family, providing more evidence that Calakmul was one of the biggest cities in North or South America in A.D. 700.

“In the Maya lowlands, lidar is a game-changing tool,” Dunning said. “If you’re in an area with a thick forest canopy, it allows you to visualize the ground surface in remarkable detail. It would take years and years to replicate with traditional mapping from the ground. And traditional mapping would miss a lot of more subtle features that lidar can detect.”

The lidar research project was authorized by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History with the support of Adriana Velazquez Morlet, director of INAH Campeche. The project is supported financially by the National Science Foundation, UC and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

It’s an utterly engineered landscape. We knew Calakmul needed an elaborate water management system to be the metropolis we see.

Nicholas Dunning, UC professor of geography

Today, Calakmul is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was the heart of the ancient Maya’s Kanu’l or “snake dynasty” between A.D. 635 and 850, named for the snake head glyphs that appeared across the Yucatan peninsula to honor its rulers. The Kanu’l dynasty ruled the geopolitics of the Maya lowlands, controlling a vast network of vassal kingdoms.

UC professor David Lentz, left, and doctoral student Stephanie Meyers conduct a botanical survey of the present rainforest at Mexico's Calakmul to compare to ancient DNA. Photo/Christopher Carr

Besides revealing more about urban planning, the lidar study also showed how the ancient Maya modified their landscape to accommodate its large urban population. The city was full of canals, terraces, walls and dams to capture water and retain soil for agriculture.

“It’s an utterly engineered landscape,” Dunning said. “We knew Calakmul needed an elaborate water management system to be the metropolis we see. Water flow and natural stream channels were modified. Just about every hill slope was transformed by terracing.”

UC’s team spent four weeks conducting fieldwork at Calakmul to help reconstruct the water, land and forest management practices of the ancient Maya. Like several other ancient Maya cities, Calakmul relied on an elaborate system of large public reservoirs.

Calakmul’s dry season could stretch for months, so retaining water was key to survival for a city that size, Dunning said.

Calakmul once was the biggest city in North or South America. Photo/Nicholas Dunning

UC researchers such as Jeffrey Brewer and Christopher Carr in UC’s Department of Geography & GIS, along with Duncan Cook of Australian Catholic University and Shane Montgomery of the University of Calgary, conducted excavations at three of the four largest urban reservoirs, which revealed meticulous engineering in its cut-stone floors and laid-stone walls anchored in clay.

“We were impressed,” Dunning said. “I’ve been working in Maya reservoirs for 30 years and the construction at Calakmul was magnificent, with beautifully laid stone walls and floor and complex hydrological engineering.”

They are examining ceramics, carbon samples and other artifacts found in the reservoirs. UC’s team also sampled excavation profiles to capture ancient pollen, geochemical signatures and environmental DNA that can help determine what wild and farmed plants grew there. This will help researchers reconstruct the land use, forestry practices and diet of the ancient Maya.

UC professor David Lentz collects a sample from an excavation at Calakmul. Photo/Christopher Carr

UC biology professor David Lentz and UC graduate student Stephanie Meyers are conducting a botanical survey of Calakmul to understand how the ancient Maya shaped the present rainforest.

Previously, UC’s interdisciplinary team helped reveal how the ancient Maya practiced sustainable farming and forestry for millennia in and around the city of Yaxnohcah near Calakmul and at Tikal in Guatemala.

Besides identifying human structures, lidar is useful in measuring the total vegetation in the rainforest, Lentz said. In this way, scientists can compare one forest to another.

“We’re living in a new age of archaeology,” Lentz said.

Their DNA analysis also revealed a lush, wild oasis growing around Tikal’s reservoirs, creating the equivalent of an urban park in the ancient city. And in Tikal’s reservoirs, they found evidence of sophisticated water filtration using crystalline quartz and zeolite imported from miles away.

“It is amazing how big the city of Calakmul is,” Lentz said. “My job is to figure out how they managed to feed all these people and get enough fuel to cook their food.”

UC adjunct research professor Christopher Carr, left, and geography professor Nicholas Dunning have collaborated on archaeology projects across Mesoamerica. Photo/Duncan Cook

Food staples of the ancient Maya such as corn, beans and manioc are unpalatable or even toxic unless cooked properly. Lentz said the ancient Maya would have needed a regular supply of firewood.

“Every society is concerned about energy. The Maya were, too. Their main source of energy was firewood,” Lentz said. “When you’re talking about tens of thousands of people, that’s a lot of firewood. It was a relentless demand.”

Informed by the new lidar maps, UC’s team and their collaborators will return to Calakmul in 2023 to continue their excavations.

Few of the residential spaces have been examined in detail, Dunning said. They hope to examine these areas in coming years.

“It is a real privilege to be working at Calakmul and with such a talented group of international collaborators who bring so many insights to the research,” Dunning said.

Dunning said archaeologists were excited to resume fieldwork postponed since 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic: “An archaeologist unable to do fieldwork is like a baseball player watching from the dugout with a broken arm and desperately wanting to get in the game.”

Featured image at top: A temple rises above the rainforest at Calakmul. Photo/Nicholas Dunning.

Researchers enjoy dinner together at their research base at Calakmul. Pictured are UC adjunct assistant professor Jeffrey Brewer, Felix Kupprat of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Shane Montgomery of the University of Calgary, Duncan Cook of Australian Catholic University and Kathryn Reese-Taylor, also of Calgary. Photo/Nicholas Dunning

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

UC‘s College of Arts and Sciences taps innovative new leadership

December 20, 2023

The College of Arts and Sciences announced Ryan J. White and Rina Williams as the newest divisional deans of Natural Sciences and Social Sciences. White and Kennedy’s inclusion will bring new focuses and structure around student success and the college of Arts and Sciences’ advancement. Both will officially begin their new terms on Jan. 1, 2024.

What is UC’s 4 + 1 program?

December 4, 2023

You may be a UC student thinking about taking your education to the next level — UC’s College of Arts and Sciences has a pathway to help you do just that. A&S has no fewer than 15 five-year programs — from biological sciences to Spanish to psychology — where you can earn both your bachelor’s and master’s degrees in just five years, versus the traditional six-year track. The Bachelors and Master’s 4 + 1 Program is designed to increase your marketability and deepen your understanding of the subject matter. And in an increasingly competitive job market, you may want to investigate an additional year of study.

Clifton Court Hall grand opening garners detailed media coverage

September 20, 2023

The University of Cincinnati celebrated the opening of Clifton Court Hall on Tuesday, Sept. 19, with a ribbon cutting, attended by approximately 200 administrators, faculty, staff and students. The event was covered by multiple media outlets.