‘Snowball Earth’ might have been slushball

Geologists find evidence that planet was not entirely frozen during ice age 635 million years ago

At least five ice ages have befallen Earth, including one 635 million years ago that created glaciers from pole to pole.

Called the Marinoan Ice Age, it’s named for the part of Australia where geologic evidence was first collected in the 1970s.

Scientists say the Marinoan Ice Age was one of the most extreme in the planet’s history, creating glacial ice that persisted for 15 million years.

But new evidence collected in the eastern Shennongjia Forestry District of China’s Hubei Province suggests the Earth was not completely frozen — at least not toward the end of the ice age. Instead, there were patches of open water in some of the shallow mid-latitude seas, based on geologic samples dating back to that period.

“We called this ice age ‘Snowball Earth,’” said Thomas Algeo, a professor of geosciences at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Arts and Sciences. “We believed that Earth had frozen over entirely during this long ice age. But maybe it was more of a ‘Slushball Earth.’”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

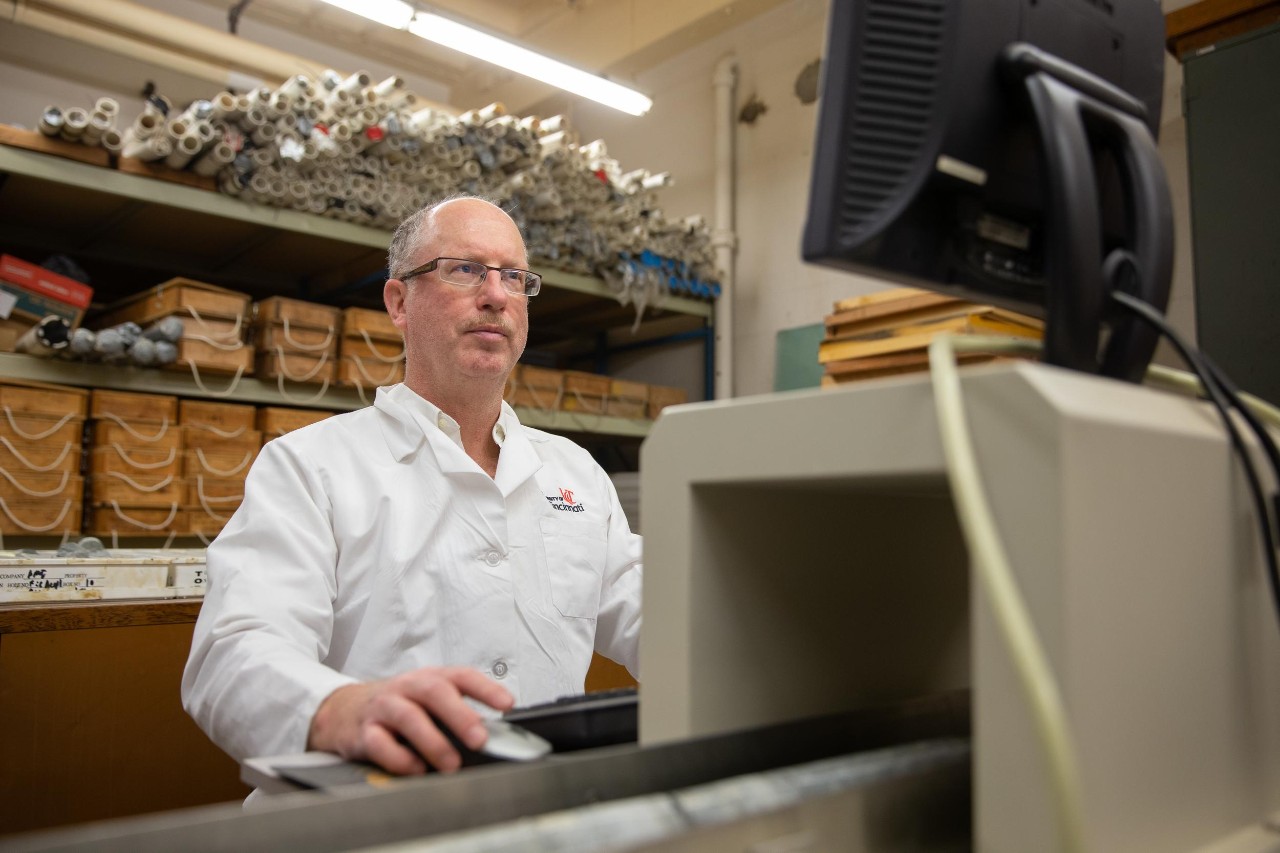

UC geosciences Professor Thomas Algeo stands in front of rock cores that he and his students analyze in his lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Scientists have found a seaweed, called benthic phototrophic macroalgae, in black shale dating back more than 600 million years. This algae lives at the bottom of the sea and needs light from the sun to convert water and carbon dioxide into energy through photosynthesis.

A team of geoscientists from China, the United Kingdom and the United States conducted an isotopic analysis and found that habitable open-ocean conditions were more extensive than previously thought, extending into oceans that fall between the tropics and the polar regions and providing refuge for single-celled and multi-celled organisms during the waning stages of the Marinoan ice age.

We don’t know for sure what triggered these ice ages, but my suspicion is it was related to multicellular organisms that removed carbon from the atmosphere.

Thomas Algeo, UC Professor of Geosciences

Lead author Huyue Song from the China University of Geosciences said while deep water likely did not contain oxygen to support life during this period, the shallow seas did.

“We present a new Snowball Earth model in which open waters existed in both low- and mid-latitude oceans,” Song said.

Song said the ice age likely saw many intervals of freezing and melting over the span of 15 million years. And under these conditions, life could have persisted, Song said.

“We found that the Marinoan glaciation was dynamic. There may have existed potential open-water conditions in the low and middle latitudes several times,” Song said. “In addition, these conditions in surface waters may have been more widespread and more sustainable than previously thought and may have allowed a rapid rebound of the biosphere after the Marinoan Snowball Earth.”

UC geosciences Professor Thomas Algeo is studying life on Earth millions of years ago. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Paradoxically, UC’s Algeo said, these refuges of life likely helped to warm the planet, ending the Marinoan ice age. The algae in the water released carbon dioxide into the atmosphere over time, gradually thawing the glaciers.

“One of the general take-home messages is how much the biosphere can influence the carbon cycle and climate,” he said. “We know that carbon dioxide is one of the most important greenhouse gases. So we see how changes in the carbon cycle have an impact on the global climate.”

Algeo said the study raises tantalizing questions about other ice ages, particularly the second one during the Cryogenian Period that scientists also believe created near-total glaciation of the planet.

“We don’t know for sure what triggered these ice ages, but my suspicion is it was related to multicellular organisms that removed carbon from the atmosphere, leading to carbon burial and the cooling of the Earth,” Algeo said. “Today, we’re releasing carbon quickly in huge amounts and it is having a big impact on global climate.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the China Geological Survey.

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Mastodon: But I would walk 500 miles...

June 13, 2022

Using isotopic analysis of its tusks, researchers tracked the ever-increasing seasonal migrations of a male mastodon across what is now Indiana, Ohio and Illinois more than 13,000 years ago. It's the first study of its kind to examine the seasonal movements of the largest extinct Ice Age animals.

How to spot a fake

December 6, 2022

University of Cincinnati chemists, geologists and art historians are collaborating to help area art museums answer questions about masterpieces and detect fakes — and teaching students about their methods.

UC student says ancient invasion can inform wildlife conservation

October 14, 2022

Ian Forsythe studies geology in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences. He examined the fossil record to examine how one well-known invasion of animals that impacted surrounding flora and fauna in the vast shallow seas that covered the Midwestern United States during the Ordovician Period. He presented his findings to the annual conference of the Geological Society of America.