UC research examines molecular impact of psychological loss

Study identifies key region of the brain as a molecular target to lessen the impact of loss

Psychological loss can occur when someone loses a job, loses a sense of control or safety or when a spouse dies. Such loss, which erodes well-being and negatively impacts quality of life, may be a common experience but little is known about the molecular process in the brain that occurs because of loss.

New research from the University of Cincinnati explores those mechanisms through a process known as enrichment removal (ER). The study highlights an area of the brain that plays a key role in psychological loss and identifies new molecular targets that may alleviate its impact.

The study was published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

The research was led by Marissa Smail, a graduate student in the Department of Pharmacology and Systems Physiology at the UC College of Medicine. She says she’s always been interested in the mechanics underlying psychiatric disorders, in particular what molecular changes happening in the brain make certain symptoms emerge and how those mechanisms can be used to alleviate debilitating conditions.

Marissa Smail, graduate research assistant, UC College of Medicine/Photo/Colleen Kelley/UC Marketing + Brand

“Most research in this field focuses on disorders such as depression and PTSD — very worthy causes but not nearly as common as loss,” Smail says. “We have all lost something and experienced the negative impact of that loss at some point. Using ER to understand the mechanisms driving this extremely common experience is a great question that not only sheds light on how we interact with the world but also has the potential to reveal novel therapeutic targets that may be of widespread benefit.”

The research examined animal models which were provided with an environment that gave them the opportunity to climb and explore and enjoy a communal experience of various toys and shelters for four weeks. The ER subjects were then removed from that environment for an extended period (one month) and researchers used a screen of the brain to look at the impact on the region of the brain with established roles in stress regulation and behavioral adaptation following enrichment removal.

James Herman, PhD, of the Department of Pharmacology and Systems Physiology at the UC College of Medicine/Photo/Colleen Kelley/UC Marketing + Brand

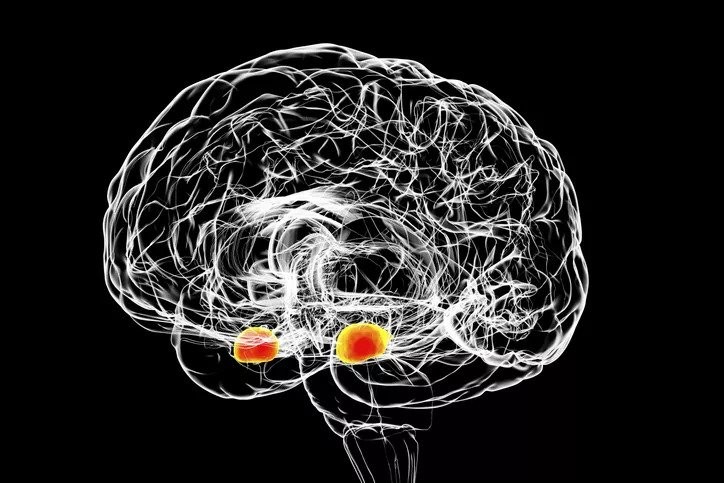

“What appears to happen is that in this key area of brain, the amygdala, the support system becomes overactive,” says James Herman, PhD, associate director of the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute, and Department Chair and the Flor van Maanen Endowed Chair for Pharmacology and Systems Physiology in the UC College of Medicine and senior author of the study. “Rather than being very [adaptable], and being able to be changed, being able to profit from experience, what ends up happening is the neurons become insulated. As a consequence of that insulation, they’re not able to drive the adaptive behaviors that you would normally see on an everyday basis. It’s not the neurons, it’s the insulators of the neurons that are causing this problem and that’s a very novel finding.”

Herman says, unfortunately, that loss is a major contributor to several mental health related conditions. It’s frequently a trigger for depressive episodes and may contribute to the epidemic of mental health consequences linked to isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Smail says one aspect of the research that she likes is that it is very interdisciplinary and collaborative, and it allowed her to explore a variety of topics and techniques to ultimately identify a novel mechanism that occurs in loss.

“Beginning with an unbiased screen meant that this was a true ‘follow the data’ project,” Smail says. “We did not expect to investigate the brain’s immune cells and supporting structure, respectively, but these endpoints led to several great collaborations and a range of molecular and behavioral experiments to understand their roles.

“The resulting mechanism described in the paper is quite novel and shares several characteristics with loss in humans, leading us to believe it is relevant for understanding this common experience.”

Lead image of the amygdala region of the brain/Kateryna Kon/Getty Images

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Local 12: 180 UC med students receive white coats, students embark on journey during pandemic

August 9, 2021

The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine welcomed 180 newly admitted first-year students during the college’s 26th annual White Coat Ceremony. The ceremony was held Friday at 10 a.m. at Cincinnati Music Hall, 1241 Elm Street. Each member of the class of 2025 were presented with a white lab coat, symbolizing entry into the medical profession. Local 12 covered the event.

GIVEHOPE and BSI Engineering Celebrate Ten Years of Driving Research

August 3, 2021

Years after two personal losses from pancreatic cancer, Cincinnati-based nonprofit GIVEHOPE and consulting firm BSI Engineering are celebrating a philanthropic partnership that has funded 13 pilot research projects at the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center.

Finding community and building a future

July 9, 2021

As a University of Cincinnati College of Medicine student, Sarah Appeadu, MD, ’21, remembers journaling on the “3 Cs” that got her through medical school: Community, community, community. Now, when she lists the people who supported her through four years of training—the last year in a global pandemic—it keeps growing: her family, her church, her classmates, and the college’s Office of Student Affairs and Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. “I look back and it was such a crucial time to really be nurtured in that way,” she says. “I’m so thankful that I had those people. It shows being around the right people really mattered. That’s my same hope for residency even.”

New York Times: Flint Weighs Scope of Harm to Children Caused by Lead in Water

February 1, 2016

Kim Dietrich, a professor of environmental health at UC's College of Medicine, is quoted in this story on the medical problems that could develop among the thousands of young children exposed to lead-contaminated water in Flint, Mich.

Cancer-Causing Gene Found in Plasma May Help Predict Outcomes for Patients

February 18, 2016

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati have discovered that a human cancer-causing gene, called DEK, can be detected in the plasma of head and neck cancer patients.

UC Receives $1.9 Million to Study Pain

February 15, 2016

Jun-Ming Zhang, MD, of the UC College of Medicine, is the principal investigator of a $1.95 million grant to study the interacting roles of the sympathetic and sensory nervous and immune systems in back and neuropathic pain models.

MD Magazine: Generic Drug Equally Effective in Epilespy

February 22, 2016

Michael Privitera, MD, a professor of neurology at UC's College of Medicine and director of the Epilepsy Center at the UC Neuroscience Institute, is featured in this story about research he led that examined the efficacy of generic drug substitution for epilepsy.

UC to Host Regional Conference for Latino Medical Student Association

February 10, 2016

The University of Cincinnati chapter of the Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA) will host a Midwest regional conference Feb. 26-28, 2016, at the College of Medicine.

Heart Disease Still Top Killer of American Women and Men, Symptoms Differ

February 1, 2016

Women tend to get palpitations, shortness of breath and "sharp" chest pain when suffering heart attacks, explains Stephanie Dunlap, DO, in the UC College of Medicine.

Philosophy Professor Explores Fine Lines Between Right and Wrong in March 29 Public Lecture

March 13, 2016

What distinguishes psychopaths from the rest of us? UC Professor Heidi Maibom offers some clues at a 3:30 p.m. lecture, March 29, in the Russell C. Myers Alumni Center.