Public gardens rally against a common foe

UC botanist helps develop an invasive species warning system for North America

A botanist at the University of Cincinnati is helping to organize public gardens across North America to develop an early warning about nonnative plants that could threaten agriculture or wild spaces.

UC College of Arts and Sciences Professor Theresa Culley is an expert on invasive species who advises federal agencies and states such as Ohio about the economic threats posed by nonnative plants.

UC Professor Theresa Culley organized a network of public gardens to look out for emerging invasive plants. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Marketing + Brand

Together with garden colleagues, she has assembled a network so far of 54 public gardens in Canada and the United States to share information about potentially invasive species they are finding in and around their properties. To date, the public gardens have reported nearly 1,000 examples that gardens are monitoring.

“The purpose is to get gardens talking to each other about plants they deem to be problematic,” Culley said.

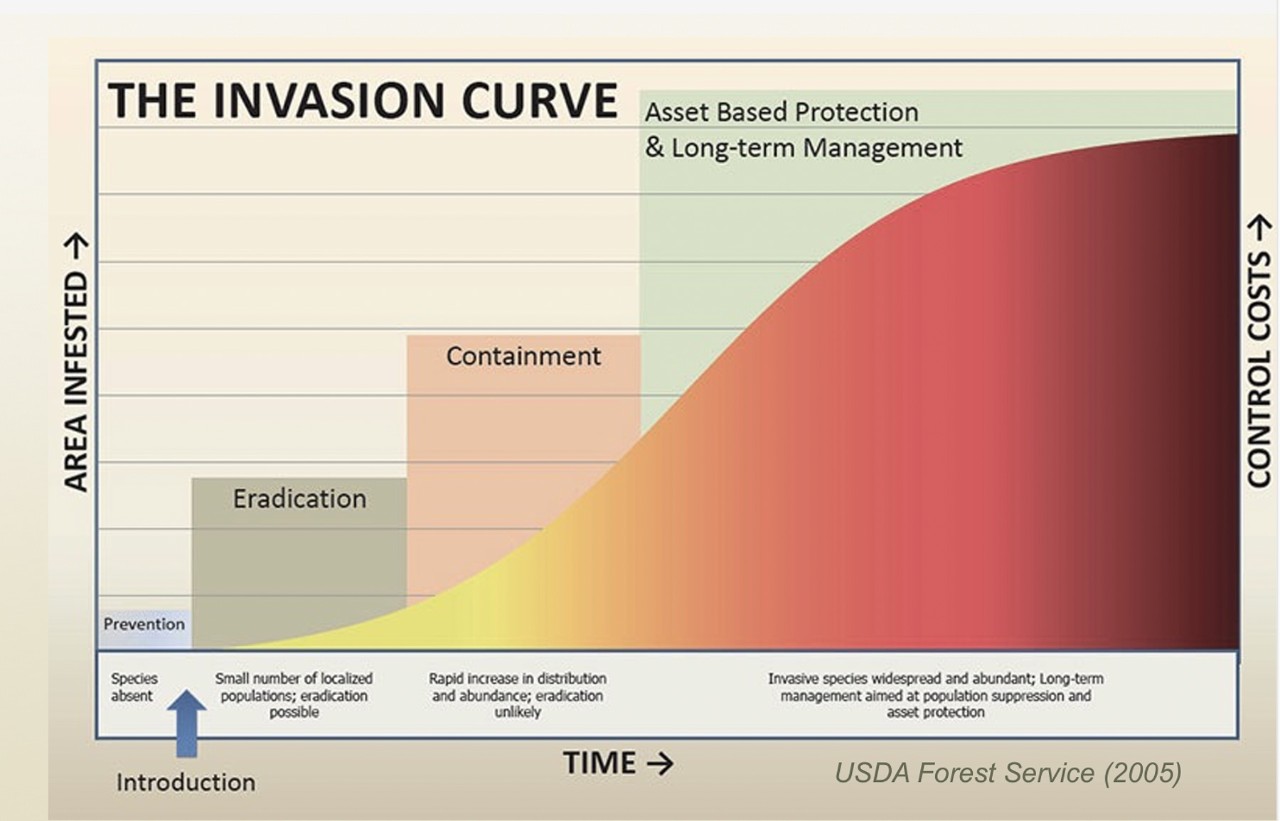

“If you look at effective invasives, by the time they spread, it’s too late. People are spending a lot of money today to get rid of honeysuckle, for example. The idea is to use public gardens as sentinels for plant invasion so we can avoid having to spend so much money and time getting rid of these plant invaders.”

Invasive species are a leading cause of biodiversity loss around the world. The Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States identifies more than 1,400 trees, shrubs, grasses and other foreign plants growing in natural areas. Invasive plants and animals cause an estimated $120 billion in damage and economic losses each year, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. The agency spends more than $140 million per year addressing invasive species to try to mitigate or prevent these losses.

The agency said preventing new invasive species from taking hold is a far more cost-effective strategy than trying to remove species once they’ve been established.

There is a lot of hope, but it requires everyone working together.

Theresa Culley, UC College of Arts and Sciences Professor

You don’t have to look far to find examples of problem plants.

Callery pear trees were introduced to the United States as a fast-growing ornamental tree with pretty spring blooms. The first cloned variety was sterile, but once other varieties were created with sturdier trunks that were less likely to split, they began to cross-pollinate and produce fruit. Soon, these trees escaped cultivation and began showing up in forests and highway edges across the Midwest.

Amur honeysuckle was a favorite landscaping bush for yards across the United States and to prevent erosion along roadsides. But this bush from China leafs out earlier in the spring than other plants and stays green through the early winter. As a result, its leaves often shade out other ground covers. And birds spread its red berries far and wide.

There has been a bigger push to address the spread of invasive species from state to state as well. States remind park visitors not to remove or introduce firewood from place to place to prevent the spread of invasive insects such as the emerald ash borer.

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum includes sections of mature forest. Photo/Cat Shiles

Issuing first alerts

The new UC collaboration is already sharing useful information.

Some public gardens are reporting that Amur corktree, an import from East Asia, is starting to show up in more wild places. Its roots have allelopathic properties, or can suppress the growth of other plants to wage chemical warfare that gives it a competitive advantage.

As a result of the public garden collaboration, they shared an alert with landscapers and nurseries urging them to sell only non-fruit-bearing Amur corktree in a bid to stem the wild expansion.

UC’s Culley said other examples include a common ground cover called wintercreeper and golden rain tree, which was introduced to North American nurseries from China and North and South Korea in the 1950s and now is growing wild in at least three states. As many as eight public gardens in the network reported that these two plants posed a potential problem as an invasive species.

“The data are important because we can prioritize strategies to deal with them,” Culley said.

Other introduced nonnative plants popping up include European buckthorn, white mulberry and Siberian elm.

The U.S. Forest Service says eliminating invasive species becomes increasingly expensive once they become established. Graph/USDA

Valuable network

Kurt Dreisilker, head of natural resources and collections horticulture at the Morton Arboretum in Illinois, has helped to organize the gardens network. It's useful for public gardens to know what other gardens are seeing across the country, he said.

“Sometimes those species may not be known as invasive so the network can get the word out ahead of time before plants become invasive,” Dreisilker said.

Gardens might be especially vigilant when they see potentially problem species pop up nearby or at multiple gardens, he said.

“I absolutely do think this network holds promise to help prevent plants from becoming invasive.”

While some public gardens focus exclusively on native plants, others cultivate a diversity of nonnative plants to introduce the public to exotic trees, flowers and bushes they might never get to see anywhere else. The gardens also help conserve rare or declining species from around the world, Culley said.

“Many of these gardens bring in plants from around the world for education,” she said. “And they’re becoming deeply involved in conservation. But there is still an inherent fear that they will be blamed for problems with invasive species that were not known to be a problem when they were planted.”

Some gardens choose to share data on invasive species as long as they are not publicly identified, she said.

UC Professor Theresa Culley has been studying ways to help stem invasive species such as Callery pear trees in Ohio and nationwide. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC

Culley said what makes public gardens good sentinels is the botanical expertise they offer along with typically extensive recordkeeping.

“The gardens are called living collections. They know where each plant is from and whether it is producing fruit,” she said. “And many have their own plant collections called an herbarium dating back decades or more.”

UC, too, maintains an herbarium containing more than 125,000 specimens.

Public gardens also can be a bellwether for the gradual creep of some species that are taking advantage of a warming climate to move north into states where winters historically have been too cold for them, she said.

Culley said she is optimistic that public gardens will be a useful source of information for park and refuge managers nationwide.

“There is a lot of hope, but it requires everyone working together,” she said.

Featured image at top: Colorful tulips are a highlight of spring at the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden. Photo/Colleen Kelley/UC Marketing + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Public gardens rally against a common foe

September 3, 2024

UC biologist Theresa Culley is organizing an international network of public gardens as an early warning for emerging invasive plants that might pose harm to agriculture and wilderness areas.

New climate change health research center under development at UC

October 15, 2024

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health has awarded a grant to the University of Cincinnati to establish the Cincinnati Center for Climate and Health.

How to make the faculty job search less discouraging

May 5, 2023

Postdoctoral researchers often get little useful feedback about ways to improve their job applications for faculty positions. So a University of Cincinnati anthropologist set up a pilot program that invited postdoctoral researchers to review each others’ application documents.