Secret of the Civil War: UC Historian Uncovers Lost History of 'Tri-racial Army'

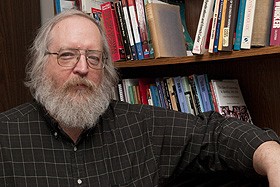

The intricacies and intrigue of the Civil War have proven to be a rich source of stories that fascinate modern-day Americans, and now UC Professor of History Mark Lause has added another chapter to that canon: a just-published book he authored details an audacious but largely overlooked effort to construct a tri-racial unit of the Union Army for fighting on the wars western-most front.

Race & Radicalism in the Union Army tells the story of a fighting unit made up of white disciples of John Brown, runaway black slaves and displaced American Indians who subverted Confederate adventurism into what later became Oklahoma near the wars front in the summer of 1863. Fighting in a battle near

, the Union force was outmanned by a 2-to-1 ratio, yet still sent the Confederates scurrying back to Texas in what Lause calls the most significant Civil War battle fought in the Indian Territory.

The men who originated the idea for the army were abolitionist followers of Brown who had come from the east a decade earlier when they heard Kansas was on the verge of being opened to slavery. They remained in Kansas, though, when Brown migrated east to plan his famous raid, as they doubted the plans chances for success.

Sidebar: Cincinnati Ties Found Among John Brown's Followers

Sidebar: Lause Adds New Book on New York Bohemians of the 1850s

After the war broke out, these people were involved in assisting runaway slaves in refugee camps and especially large numbers of Indians who had been driven out of the Indian Territory, says Lause. So they came up with this plan for putting together a multiracial Union Army on the western frontier. It was going to consist of Indians who were raised and recruited as Kansas regiments and would go as home guards back into the Indian territory, and it included the first organized group of black soldiers that went into combat in the war.

The black soldiers, according to Lause, had their first battle experiences serving as part of the Indian regiment a year earlier than the famed 54th Massachusetts unit that was depicted in the movie Glory. (All the newspaper reporters of the time were in the east, Lause theorizes, in explaining the discrepancy in their relative fame.) The black soldiers eventually came to fight as their own unit, the 1st Kansas Colored regiment.

The idea of a tri-racial army was a conscious decision, an experiment tried with the federal governments support in exploring what a post-Civil War America could be like, according to Lause.

What took place poses a challenge to a lot of the ideas that sort of denigrate the ideology of Unionism, and the ideology of wartime republicanism with regard to race, says Lause, referring to those who diminish the Union sides commitment to race issues. This was a clear experiment, intended to be an experiment. It was ultimately, though, sabotaged in the course of things.

The immediate history in the region set the stage for the events Lause documents.

Indian Territory before the war covered much of Eastern Oklahoma, with the five civilized tribes of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminoles in the region. Government-appointed agents who had a monopoly on trade with the Indians were appointed by the southern-sympathetic Democrats up until Lincolns election, and had a long history of corrupt practices in their Indian dealings.

Once the war began, the Indian agents lined up their territories and their loyalties firmly on the southern side. Indeed, Lause notes that the most influential of the Indian agents at the time, Douglas Cooper, immediately switched roles to become a Confederate general. Indians who remained in their territory were subject to being forced to fight for the Confederate side. Many chose to try and leave, with up to 20,000 coming to Kansas as refugees as the territories were essentially de-populated.

In dealing with Lincolns federal government, the Indians actually sought neutrality in the conflict, and the government concurred. But it was not a realistic option in the face of the burdens of supporting the refugees in Kansas and also Missouri. What was launched as an alternative plan was the idea of financing and organizing Indian regiments from out of these displaced groups to go back to Indian Territory as a home guard, thus creating the Indian component of what would become the tri-racial army.

In 1862, working in cooperation with the John Brown followers as the units military leaders, the Indian regiments actually retook a large chunk of the Indian Territory from the Confederates. They had to pull out, however, when it proved impossible to secure supply lines that far south. That began a period that Lause compares to Eastern European-style warfare, where the war front fluctuated positions back and forth many times west of the Mississippi, leaving the region in ruins. Guerilla warfare and banditry were frequently practiced.

The escaped slaves who had been scattered among the Indian units during that time eventually coalesced into their own regiment, adding the 1st Kansas Colored to the roster of forces available to the Union in the region in the summer of 1863.

Confederate forces at the time had their eye on the Union stronghold of Fort Gibson. By July 17, 1863, they were within 20 miles of the fort with an army of 6,000 men, largely made up of units of white soldiers who had come north from Texas. Having heard they would likely face a unit now of escaped slaves, the Confederates had such confidence that the slaves would drop their weapons and flee if engaged in a fight that, despite supply line issues of their own, they emptied one supply wagon to carry 400 shackles among their equipment taken north. Their plan was to capture the fleeing slaves and re-sell them into slavery, thus financing their campaign, according to Lause.

Gen. James Blunt

The tri-racial army had slipped out of Fort Gibson under the cover of darkness the previous night. With only half as many men operating under the command of Gen. James Blunt, a physician from Maine who had come west as an abolitionist, the Union forces engaged the Confederates in a day-long battle fought in heat and heavy rain. Steadily, they drove the Confederates back until the battle ended in a full-on Confederate retreat back towards Fort Smith in Arkansas and safety. The soldiers of the 1st Kansas Colored, who had played a major role in the battle, ended up toying with the unused shackles the Confederates had left behind.

It was a relatively small campaign as far as Civil War battles go, but it was a remarkably telling one, Lause says.

The Confederates, in fact, would never again be an occupying force in Indian Territory. In the larger picture, the Battle of Vicksburg would be resolved within the same month, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River and cutting ties between Confederate forces in the south and those in the trans-Mississippi region. While the Union was able to reinforce its armies in the east, Confederate troops were bottled up and couldnt match the Union forces in their surge back to the battlefields in the east.

That surge eastward also meant, though, that Union support to the region became very weak, Lause points out. Shortages became common, even though the Indian Home Guards continued to control the Indian Territory and posed a threat from the western flank that any Confederate plans to drive north could not ignore.

The members of the 1st Kansas Colored regiment also ultimately paid a heavy price they were massacred in 1864 protecting Union supply lines in Arkansas. They met up with a stronger Confederate force containing many of the same men from Texas they defeated at Honey Springs, and they were not only defeated, but any troops left wounded on the battlefield are simply shot, with the Confederates justifying the actions by considering the men slaves in rebellion.

In a final ugly turn, the assassination of Lincoln led to another betrayal of the Indians who had loyally fought for the Union. The federal government did a 180-degree turn and claimed that the treaties the Indians had made with the Confederate forces during the war, which came virtually at gun point, abrogated any standing treaties with the federal government. With profiteers from the railroads and other interests crowding in, the government then claimed the rights to impose all new and less desirable boundaries on the Indian nations.

It was a golden opportunity to revisit this question of race. You not only had blacks and whites fighting side-by-side much closer in the trans-Mississippi than in the other theaters of the war, you also had the Indians there and you had a government who was intending to doing something about it, at least verbally, says Lause.

But ultimately he says it was all undone because there was money to be made doing things the old way, but not in the new way that would have resulted had the tri-racial army been seen as a model for racial cooperation. (Business interests) became much more important than the opportunity that presented itself, and thats the big tragedy of the war -- it leaves issues that will still have to be re-fought in the future.

Related Stories

Alumni to be honored at gala recognizing UC Black excellence

January 13, 2025

Outstanding achievements within the University of Cincinnati family are the focus of the 11th annual Onyx & Ruby Gala, to be hosted by the UC Alumni Association’s African American Alumni Affiliate on Feb. 22 at Great American Ball Park in downtown Cincinnati.

Monica Turner elected chair of UC's Board of Trustees

January 13, 2025

P&G executive Monica Turner was elected Chair of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees. Gregory Hartmann was elected Vice Chair, and Jill McGruder was elected as Secretary.

Why is Facebook abandoning fact-checking?

January 10, 2025

UC Professor Jeffrey Blevins talks to France TV Washington about Facebook's decision to stop fact-checking public posts and allowing community notes instead to address disinformation.