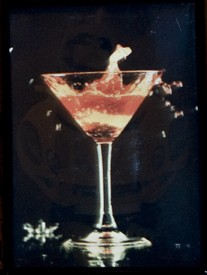

Shaken, and Not Stirred But What About the Clathrates?

University of Cincinnati Professor Dale W. Schaefer, in the Chemical and Materials Engineering Department of UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science, is part of an international team of scientists studying to see if there is a scientific way to measure structure in vodkas. UC collaborated with scientists from Moscow State University.

Since vodkas are 60 percent pure water and 40 percent pure ethanol (ethyl alcohol), many people conclude that vodkas are uniformly tasteless. As reported recently in the "Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry," in their paper, "

Structurability: A Collective Measure of the Structural Differences in Vodkas

," the researchers found that vodkas differ in their physical structure, which could lead to perceptible differences in taste.

Nobel prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling proposed that the narcotic effect might be due to the formation of crystals called clathrate hydrates in the brain. I think that idea is wrong, but we propose a cage-like hydrogen-bonded structure, which is a liquid analogue of a clathrate, says Schaefer. Water alcohol mixtures are known to form clathrate hydrates below -80 degrees C, which is why we proposed a transient cage-like structure in the liquid at room temperature.

Schaefer posited that the structures were responsible for variation in taste. The team then tested five vodkas: Skyy, Belvedere, Stolichnaya, Grey Goose and Oval. They found that vodkas differ in the prevalence of the cage-like structure. Computer simulations by Schaefer's group show that trace impurities control the structure.

Still, Schaefer says that it takes a discerning taste to distinguish between vodkas.

It is likely that less than 50 percent of the population can distinguish one vodka from another, he says. Our findings could only apply to the 50 percent who can distinguish. As Walter Lippman said, The music means nothing if the audience is deaf. Some even claim there is a genetic component to alcohol perception."

The next step is to test the hypothesis in the paper by testing subjects with the ability to distinguish brands in blind taste tests. At present there is no more funding for the project now.

So until we get more funding, we are no longer players, says Schaefer.

Much of the analysis was done by two post-docs: Dan Wu, now at Dow AgriChemicals, and Naiping Hu, who is still in Schaefers group. Masters student Kelly Cross also worked on the project.

The Moscow team was led by Svetlana Patsaeva, whose father was Viktor Patsayev, a Soviet cosmonaut who was killed in the Soyuz 11 disaster.

By the way, Ian Flemings James Bond had another preference: he always preferred Russian or Polish vodkas if they were available. Schaefers researchers would be happy to know that.

Watch a

video of Kelly Cross demonstrating the scanning electron microscope

.

Related Stories

UC recognizes students for innovation achievement and leadership

April 30, 2025

Read about the University of Cincinnati’s undergraduate innovation awards for 2025.

Mechanical engineering scholarship honors alumnus

April 28, 2025

An estate gift from Pringle and her husband, Thomas Pringle, honors Sullivan with the creation of the Harold Richard Sullivan Endowed Scholarship Fund. The scholarship supports mechanical engineering students at the UC College of Engineering and Applied Science with a preference to students who are current or former service members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

UC Chicago Alumni to be honored at annual Chicagoans for Cincy!...

April 25, 2025

The University of Cincinnati Alumni Association and the Chicagoans for Cincy! Celebration committee, a group of dedicated alumni living in the Chicago area, will honor three outstanding Bearcats at this year’s annual Chicagoans for Cincy! Celebration. The event will take place Thursday, May 8, at 6 p.m. at Loft Lucia in Chicago’s West Loop neighborhood.