Olympic Oddities: See Surprising Historical Highlights About Ancient Olympic Games

The Olympics as they were held in ancient Greece were something like a combination of the Super Bowl, Easter at the Vatican and celebrity people watching part sports and part religion where eager hometown fans clustered together in the stadium at Olympia to cheer on celebrated native sons.

And just as athletes do today, ancient Olympic competitors capitalized on their prestigious victories in various ways whether via marketing or later political and even military careers.

So, while today we might expect to see the image of a gold-medal winner on a cereal box,

Olympic winners in 700 B.C. Greece might instead take the olive oil coating their bodies if they werent too dusty, sweaty or bloody from competition and scrape it off to sell to fans.

(The ancient athletes covered themselves in olive oil for aesthetic reasons and because they believed it warmed the muscles.)

Its easy to see that the Olympics of ancient Greece may offer a perhaps overlooked lens to the modern games soon to begin in Sochi, Russia.

Thats according to Andrew Connor, a doctoral student in the University of Cincinnatis Department of Classics, who studies aspects of the ancient world, has previously co-taught a UC course on Ancient Athletics and provides regular community and school presentations on ancient sports.

From Connor, here are other unexpected insights into the ancient Olympics, which are believed to have been first held in 776 B.C. and then continued for centuries, held every four years at Olympia:

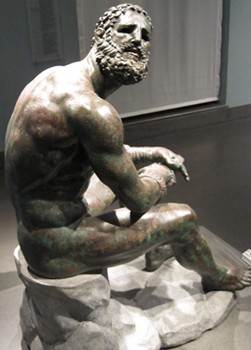

THEY WERE THE NAKED GAMES

(Except for Charioteers)

Ancient Olympic competitors all of them men

competed in the nude

. That is, except the drivers in the chariot races. (Serious crashes and accidents were common in chariot races. Thus, apparel afforded some protection if the horses dragged the charioteer as the result of a mishap.)

WOMEN WERE NOT WELCOME

For the most part, women were not permitted among the spectators and certainly not among competitors. Those attending and watching camped out in a tent city for the five days of the ancient games. According to the legal code at the time,

any woman found at the site during the games would be thrown off a nearby mountain.

One exception: the priestess of the Greek goddess, Artemis, was permitted to watch the games. And other women did find their way to the Olympics. For instance, one woman named Kallipateira from a famous boxing family on the island of Rhodes served as her sons coach. She disguised herself as a man in order to continue her sons boxing training in the required 10-month training period at Olympia ahead of the games. In late fifth century B.C. games, Kallipateiras son did indeed win an Olympic boxing competition, and she was discovered as a result. Happily, given the prominence of her family, Kallipateira was let off with a warning, said Connor.

THE ROMAN EMPEROR NERO COMPETED IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES

The Olympics were generally open only to men of Greek origin from either mainland Greece or the far-flung Greek colonies that stretched from modern-day Spain to Russia. However, the Roman Emperor Nero was permitted to participate, and he raced as a charioteer in 67 A.D. (He was permitted to participate because, well, he was emperor. In addition, he was actually much loved in Greece because he had granted the Greeks tax freedom.) In the end,

Nero didnt even finish his chariot race, but he was nevertheless crowned the winner.

After all, the judges werent stupid. But his name was expunged from the list of Olympic winners upon his death the following year.

Marble copy of the Diskobolus

WINNING WAS WORTH EVERYTHING, INCLUDING THE ATHLETES LIFE

The ancient Greeks called the games the Olympic Agones, the Olympic struggles. They were a way to prove that you as an individual (there were no team sports) were the greatest and to be immortalized on a roll of winners. Nothing short of first place was acknowledged or awarded. In fact, the games were sometimes so intense that it was possible to be killed in Olympic events like boxing, wrestling and pankration (no-holds-barred combat). Said Connor,

In one famous pankration match, one contestant died just as his opponent surrendered and gave up.

Given the conundrum, the judges awarded the victory to the fighter who died because he best represented the struggle to be the best.

WITH NO PUBLIC ADDRESS SYSTEM, THE TRUMPET BLOWER AND ANNOUNCER ALSO WON OLYMPIC LAURELS

Greeks also competed to serve as the ancient public address system

. The job went to the guys who could blow the trumpet the loudest and shout the loudest in order to tell the crowd about the winners. Those who fulfilled these two roles had their names listed as Olympic winners too.

ANCIENT OLYMPIC PAYOFF: FREE FOOD FOR LIFE AND YOU MIGHT BECOME COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF

As mentioned above, the material payoff for an Olympic win came in various forms. For instance,

winners might immediately scrape the olive oil off their bodies and sell it to fans.

And some city-states offered Olympic winners free food for life. Of course, some winners did even better, according to Connor. For instance, one wrestling champ from Sicily (Milo of Croton) came home from his Olympic win and was put in charge of the army since Croton was under attack. He then won the local war wearing his Olympic laurels while doing so.

THE START DATE FOR THE ANCIENT OLYMPIC GAMES WAS ON A STRICT (LUNAR) STOPWATCH

Every four years, the ancient Olympics were precisely planned, with pinpoint start dates for official training and for the games themselves. In fact,

there was only one acceptable excuse that a would-be competitor could use for arriving late to training or the games: Shipwreck.

Umpires and athletes went into training at Olympia two months before the winter solstice and trained for the following 10 months. The games began two days before the second full moon after the summer solstice.

Starting blocks at Olympia Stadium.

OLYMPIC-SIZED FINES FOR CHEATING

The ancient games were held to honor the Greek god Zeus, and no one in ancient Greece wanted to be on Zeus bad side. (He had a notorious temper.) So, cheating in any way (like bribing an opponent to take a dive) or breaking the ancient rules of good sportsmanship in contact sports like boxing and wrestling (no gouging of the eye or mouth and leave the groin alone too)

earned the penalty of being hit with a big stick by the referee if an offense occurred during competition; the possibility of a public whipping (a punishment usually reserved for slaves); immediate disqualification; and a massive fine.

That fine would pay for a bronze statue of Zeus, with the name of the cheater, a description of his offense and the amount of his fine displayed at the base. Said Connor, After a while, they had a road at Olympia lined with these statues.

THE ANCIENT GREEKS LOVED THEIR OLYMPIC SOUVENIRS AND THE OLYMPIC MENU

Just as todays travelers to Sochi, Russia, will bring back souvenirs from the games, so did the ancient Greeks. Souvenirs of the ancient games consisted of wooden statues of the athletes, as well as lamps and vases depicting athletic scenes which, yes,

ancient Greeks displayed around the house just as we do our own sports paraphernalia.

The athletes and the spectators also ate well at the games, which were part of a religious observance requiring the sacrifice of 100 cows to open the games. While the bones and fat of the cows were sacrificially burned, the beef was eaten (at a time when the Greek diet chiefly consisted of olives, lentils, vegetables and fish).

Entrance passageway tunnel for ancient athletes entering the stadium at Olympia.

AS WITH TODAYS OLYMPICS, THERE WAS A PARADE OF PARTICIPANTS IN ANTIQUITY

The first procession of athletes by country in the modern Olympics occurred in 1928 and continues to this day. However, this modern procession echoes a religious procession held at the ancient Olympics where athletes and ambassadors from each represented city-state marched together.

THE ANCIENT OLYMPICS HAD FIRE, BUT NO TORCH RUN

The practice of runners carrying an Olympic torch from Greece to the site of the modern-day Olympics began with the Berlin Olympics of 1936. While there was no torch relay connected to the ancient Olympics, fire was a part of the games. At Olympia, a fire was permanently lit on the altar of the goddess Hestia. Fires were also lit at the temples of Zeus and Hera.

Related Stories

Modern tech unlocks secrets of ancient art

May 7, 2025

A Classics researcher at the University of Cincinnati is using state-of-the-art technology to learn more about the mass production and placement of votives in ancient Greece.

UC students destigmatize stress in nursing

May 7, 2025

UC nurse anesthesia graduate students lead a research-based effort to address stress and burnout in nursing, coping strategies, and the importance of mindfulness and peer support.

First Marian Spencer Scholar graduates during UC’s Spring...

May 7, 2025

Katelyn Cotton, a political science major, became the first student in the Marian Spencer Scholarship program, to graduate from the University of Cincinnati during the May 2 Spring Commencement ceremonies.