New Model, New Choices for Wound Healing Using Electrical Fields

Scientists at the University of Cincinnati are working on ways to wirelessly stimulate the bodys own electrical fields to improve self-healing.

Electrical fields (EFs) that occur normally in the human body regulate various body, organ and cell functions, including growth and skin wound healing. When the bodys ability to heal normally is compromised by diseases like diabetes, manipulating these EFs with outside electrical signals can have a positive effect on skin, brain, muscle and vascular cells, just to name a few.

In previous studies, however, maintaining optimal EFs has been difficult to achieve, largely because of an incomplete understanding of how an external signal alters the EF in the cell and what cell compartments are affected.

Now, University of Cincinnati physics and biomedical engineering researchers are demonstrating, with the help of a newly created computerized numerical cell model, how wirelessly applied electrical stimulation from a device currently under a provisional patent directly targeting injured or abnormal cells can regulate cell function and increase healing with much greater accuracy.

Using this numerical cell model that realistically simulates a living cell, the researchers can accurately predict the electrical fields inside a cell membrane cytoplasm and in its surrounding environment.

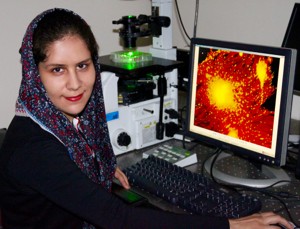

UC physics doctoral student Toloo Taghian explains that the response of a cell to external electrical signals depends strongly on whether the cell is suspended in an electrolyte fluid (such as blood or intestinal fluid) or is attached to a tissue substrate. And the type of the substrate has a strong influence on the cell response.

Therefore, a key finding of this study is that the extracellular environment can regulate the effects of an applied EF on the cell by controlling the electrical field inside and outside of the cell membrane.

Three scientists look closely at a computer screen of a magnified organic cell.

In an interdisciplinary collaboration with Andrei Kogan, associate professor of physics in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences, and Daria Narmoneva, associate professor of biomedical engineering in the College of Engineering and Applied Science, doctoral student Taghian published the results of this study in the May issue of the Journal of Royal Society Interface titled

Modulation of Cell Function by Electric Field: A High Resolution Analysis

.

A POSITIVE MODELING EFFECT

"Our findings demonstrate striking differences in cell responses between cells that are suspended in a medium (fluid) and cells attached to a dielectric substrate, says Taghian.

In other words, cells that float around in electrolyte fluid carry different amounts of induced EFs than cells attached to tissue such as skin, vascular and brain cells, or muscles and other organ tissue, and quantifying these differences with consistent results in past studies has been difficult until now.

In real life and with actual cells, either in an in-vitro environment or inside our bodies, the cells are usually attached to some kind of substrate or to other cells, says Taghian. So if we want to model the fields effectively, we have to model the cell in its physiological environment. The electrical field induced in a cell changes depending on the cells shape and substrate it is attached to.

HEALING THROUGH STIMULATION

In low-frequency stimulation, Taghian and the researchers discovered a significantly higher EF in the side of the cell that is attached to a substrate than in the other parts of the cell membrane. This suggests a higher electrical effect on the adhesion receptors of the cells, which further punctuates the importance of this study.

Taghian believes that development of electrical field therapy needs a numerical model that can accurately explain the concept and assign a true value for effective electrical stimulation. The unique numerical cell models created for this study separate it from the previous studies, making this model more realistic and physiologically relevant.

Two scientists look at a computer screen of a cell model.

This is especially important when it comes to analyzing cells that are in distress. Taghian explains that human bodily fluids are ionic and that ionic flow has a different concentration in the wounded area, which consequently results in establishing an ionic flow from the intact part of the body toward the wound. This ionic flow called wound current guides cells to the wounded area to help it heal effectively, says Taghian.

To enhance that healing process, especially when a disease prevents sufficient healing naturally, the researchers have shown success by increasing the electrical field through wireless EF stimulation in the affected area.

Using the numerical cell model to predict an accurate EF induced in all parts of a cell, Taghian applied a variety of very low to very high wireless EF frequencies to successfully enhance the cells healing response.

SECRET TO HER SUCCESS

The secret to the success of this project lies in how the positive and negative charges within a cell redistribute themselves after receiving the EF during wireless stimulation.

The beauty of the process is enhanced by the how the electrolyte and the dielectric respond differently, says Taghian. In low-frequency electrical stimulation, wherever you have electrolytes the induced EF will eliminate the field in the electrolytes or in the culture medium. So whatever is not an electrolyte such as the cell membrane will keep the induced electrical field within itself.

It means that you can concentrate as much electrical field as is needed in the cell membrane to activate membrane initiated effects, yet limit the EF in the electrolytes (fluid) where it may cause heating. In low-frequency electrical stimulation we are generating an EF only within the cell membrane, even using high voltage if it is needed.

Color slide of a computerized numerical cell model.

Taghian can now target different cell compartments based on the field frequency. In low frequency she can target only the cell membrane, but in higher frequencies she can indeed affect the intracellular space, the cytoplasm or the cell membrane whatever area she wants. Now she has more choices.

Moreover, in high frequencies where she achieves an EF induced in the cytoplasm, the charged proteins can interact with the induced field and can change their conformation and activate successful intracellular healing responses.

Because this process allows the ions to move around and through the cell to positively affect the adhesion and other intracellular healing responses, the use of EF in high frequencies when necessary is now possible without overheating the cell, eliminating unnecessary burns.

Her findings, now a subject of a provisional patent, provide key information for understanding the methods of cell responses to wireless EF stimulation for future therapeutic applications, which can be successfully used by anyone in the scientific community. Modifying cell responses using precisely applied wireless EF shows great promise for the development of safe and effective EF-based clinical treatments for chronic wound healing and more.

Aligning with

, Taghian's interdisciplinary research team will continue to work toward applying their electrical field research in the direction of human research studies.

FUNDING:

Funding for this project was secured through financial support from the University of Cincinnati Physics Department (A.K. and T.T.), NSF DMR 1206784 and DMR 0804199 (A.K.), NIH 1R21 DK078814-01A1 (D.N.), the University of Cincinnati Interdisciplinary Faculty Research award (D.N. and A.K.), University of Cincinnati BCEE seed award and NSF LEAF (ADVANCED IT) (D.N.).

OTHER RELATED NEWS:

Related Stories

UC engineer applying generative AI to smart manufacturing

March 31, 2025

Manish Raj Aryal, a PhD student in mechanical engineering at the University of Cincinnati, is working on revolutionizing manufacturing systems through generative AI, leveraging AI systems to develop manufacturing assistant chatbots. He came to UC for his master's degree and continued researching as a PhD student. He was named Graduate Student Engineer of the Month by the College of Engineering and Applied Science (CEAS).

Exploring careers in robotics engineering: A path to the future

March 28, 2025

Discover robotics engineering careers: skills, paths, and opportunities in manufacturing, healthcare, and space. Explore salaries and how to start at UC’s CEAS.

Mechanical engineering student helps send science to the moon...

March 28, 2025

UC student Ilyas Malik aids Firefly's lunar mission for NASA's CLPS. Explore his journey, UC's co-op impact, and aerospace insights. Discover how education transforms career paths in space exploration.