UC experts’ Maya research featured in Cincinnati Museum Center exhibit

Interdisciplinary gallery immerses visitors in ancient Maya civilization

The Cincinnati Museum Center officially opened Maya: The Exhibition July 17, and with it a companion exhibit developed by an interdisciplinary team of Maya experts from the University of Cincinnati.

Originally slated for a March 14 opening, the exhibits were shuttered until late July after the state lockdown resulting from the novel coronavirus pandemic.

In its U.S. premiere, the exhibit features more than 300 original objects—from massive, carved-stone slabs to elaborate jade jewelry to tools and everyday items—that explore Maya culture. From 1000 BC to 1500 AD, Maya civilization spanned the jungles of Mexico, Guatemala and Belize, noted for its innovations in science, agriculture, astronomy and mathematics.

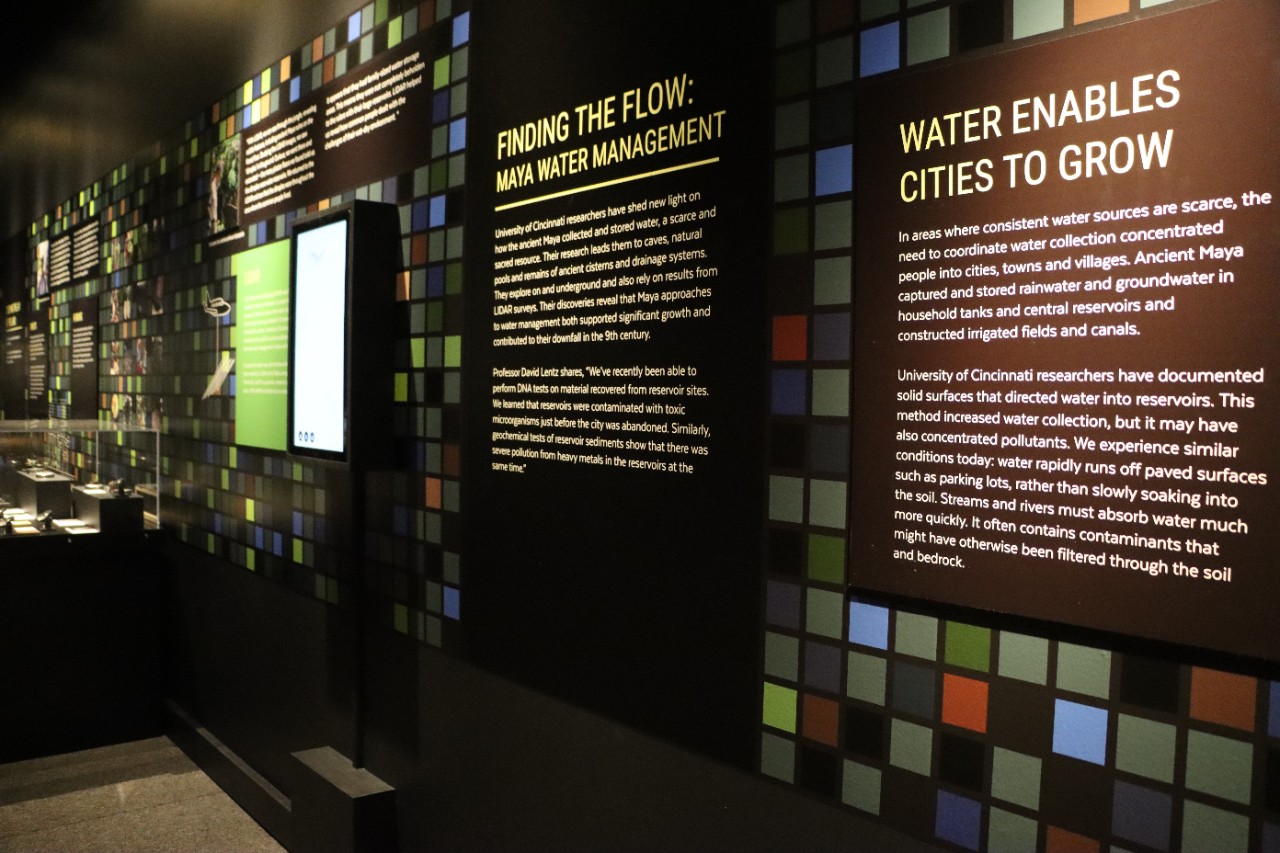

The UC exhibit at Cincinnati Museum Center explores Maya water usage. Photo/Beth Vleaminck

As visitors wind through the main gallery, they enter the companion exhibit, University of Cincinnati Lessons from the Maya, which brings UC expertise to the exploration of the civilization and its demise, and insights into how we can apply those lessons to contemporary environmental challenges.

Divided into sections examining land use, water management and material culture, the exhibit showcases the scholarship of several disciplines — and decades of study — from UC College of Arts and Sciences researchers David Lentz, professor of biology, Sarah Jackson professor of anthropology, and professors of geography Nicholas Dunning and Christopher Carr.

A call to action

There are many lessons in Maya water management with applications today, says Lentz, co-editor of “Tikal: Paleoecology of an Ancient Maya City” (Cambridge University Press).

“The Maya are a major harbinger for our time,” he says. “We have insight into what’s coming, but they didn’t.”

At Tikal, in northern Guatemala, the Maya collected rainwater in reservoirs that ringed the city, collecting water through the rainy season for drinking water and agricultural purposes. A recent, groundbreaking study by Lentz and a team of UC researchers published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports showed that highly toxic levels of mercury in the water was in part to blame for that city’s demise.

UC professor of Biology David Lentz, a Maya scholar and contributor to the exhibit.

Lentz points to blue-green algae blooms caused by runoff pollution in Lake Erie today as an example of how many of the challenges faced by the Maya exist in the present-day.

“All of these questions about the environment are so critical today,” says Jackson. “I think there are concrete lessons … about the various ways human beings have over time managed to respond to climate pressures, and climate issues. Because that is how this has been managed in other times and places, and so we shouldn’t be hesitant about doing the things we have to do to change.”

I think there are concrete lessons ... about the various ways human beings have, over time, managed to respond to climate pressures, and climate issues.

Sarah Jackson, UC professor of Anthropology

Hands-on experience

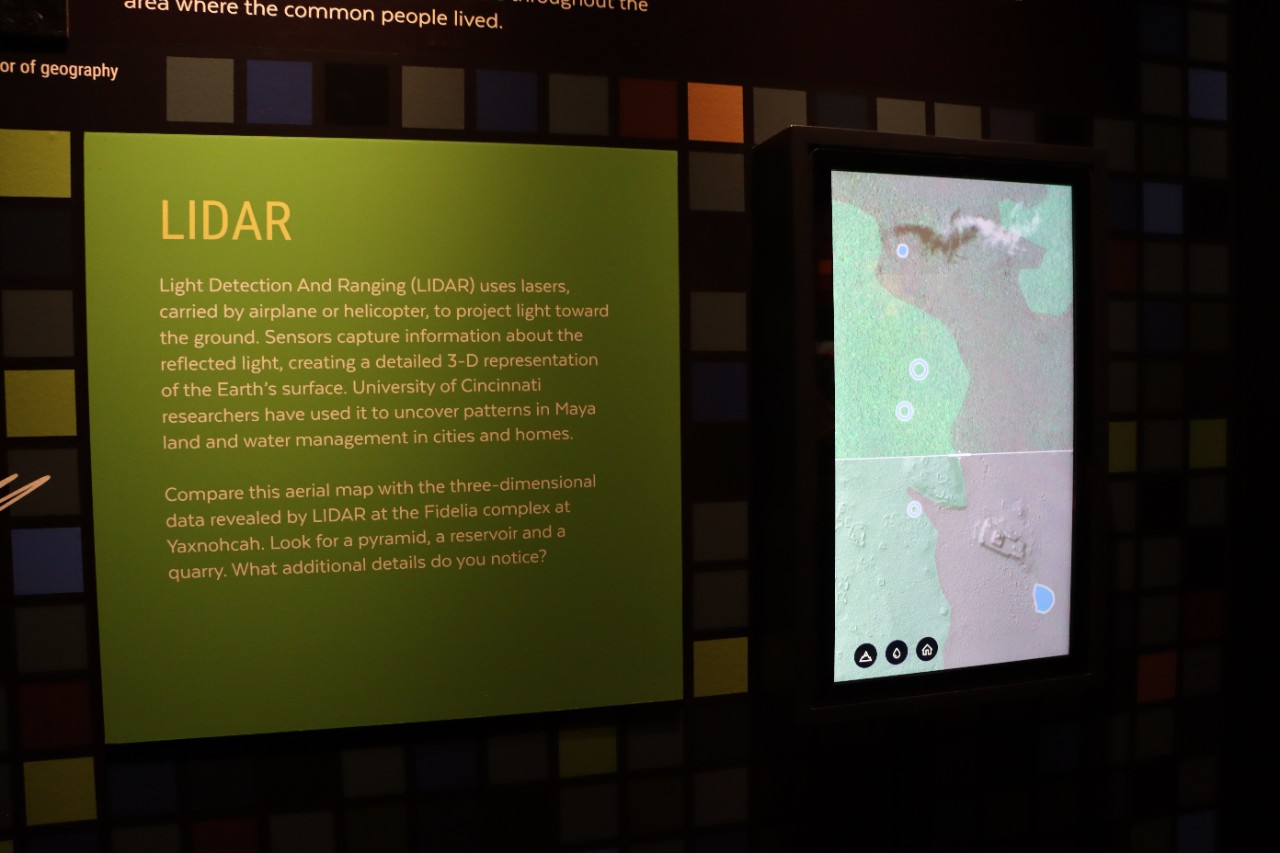

Storytelling through interaction brings the UC exhibit to life, where visitors use a LIDAR (Light Detection and Radar) simulator to explore terrain, examine botanical samples of carbonized seeds and wood to understand the Maya diet, and learn to interpret day-to-day items as the Maya would have seen them.

Visitors discover how common items today transform into material items the Maya categorized with different labels, such as ‘stony,’ and ‘bright, shiny, wet,’ which Jackson says sheds insight into Maya interpretation of the material world.

“We start to have glimmers here that remind us that all of these things are culturally constructed, how we make sense of lots of domains of our everyday life,” Jackson says.

The LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) interactive station allows visitors to uncover clues about Maya civilization. Photo/Beth Vleaminck

Visitors also can interact with simulated LIDAR, which Carr and a team of researchers used on site in Yaxnohcah, Mexico, to penetrate the dense jungle and uncover clues about Maya reservoirs and other geographic details.

“The ancient Maya were very inventive,” Dunning says. “They problem-solved, adapted to the environment quite effectively, but ultimately like just about any other human population, they came up against limits to what they were able to do in terms of mediating the environment they happened to be in, water management being one example of that.”

Pathways to the past

Modern archaeology is a multi-disciplinary team endeavor, often involving collaborators from a variety of institutions and countries, Dunning says. “For example, the Yaxnohcah Archaeological Project is a collaboration between investigators from the University of Calgary, Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, as well as our own team from UC.”

Including the disciplines of geography, biology, anthropology and archaeology brings a dimension to the exhibit that helps visitors reconstruct the Maya period from a variety of perspectives.

“Archaeologists are always taking these fragmentary bits and trying to reconstruct elements of a past period, of a past culture,” Jackson says. “But there’s so many pathways to get there … there are lots of different ways to understanding the past.”

Maya: The Exhibition is open through January 3, 2021. For hours, ticket prices and more information on the exhibit, visit the Cincinnati Museum Center.

Featured image at top: Entrance to the University of Cincinnati Maya exhibit at Cincinnati Museum Center. Photo/Beth Vleaminck

Related Stories

Leaders, scholars, changemakers: CoM students earn prestigious...

May 13, 2025

The University of Cincinnati's College of Medicine is proud to celebrate the outstanding achievements of three remarkable students, who have been recognized with two of the university’s highest honors.

CCM welcomes new violin faculty member Kenneth Renshaw

May 12, 2025

UC College-Conservatory of Music Dean Pete Jutras has announced the appointment of Kenneth Renshaw as CCM's new Assistant Professor of Violin. His faculty appointment officially begins on Aug. 15, 2025. Born and raised in San Francisco, Renshaw came to international attention in 2012 after winning First Prize at the Yehudi Menuhin International Violin Competition in Beijing. He was also a prize winner in the Queen Elisabeth International Violin Competition of Belgium, and First Prize recipient of the inaugural Manhattan International Concert Artists Competition.

Ladies of Anavlochos: Tech sheds light on ancient Greek figurines

May 12, 2025

The Greek Reporter and other news outlets highlighted work by the University of Cincinnati's Department of Classics using experimental archaeology to explore rites behind Bronze Age figurines discovered at Anavlochos, Crete.